Ingenious: The best

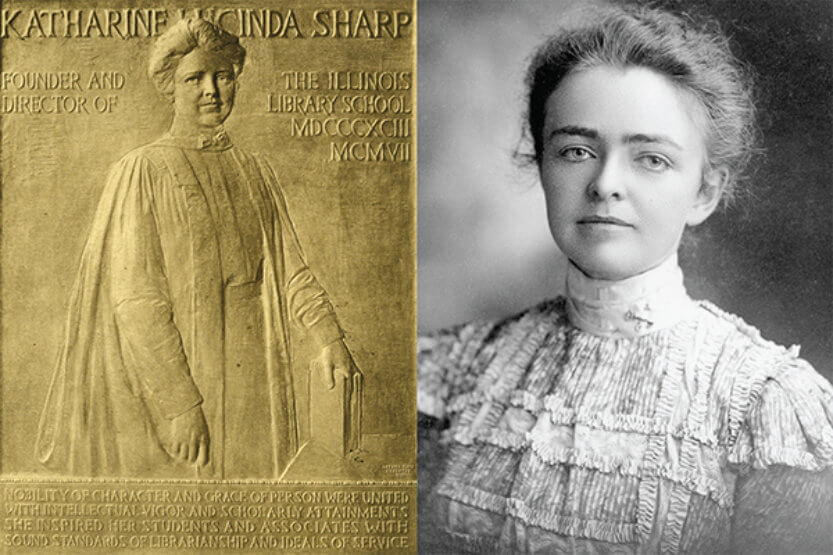

Thanks to the foundational efforts of Katharine L. Sharp, today UI has the top-ranked information science program and graduate library in the U.S. and one of the nation’s largest research libraries. (Images courtesy of UI Archives)

Thanks to the foundational efforts of Katharine L. Sharp, today UI has the top-ranked information science program and graduate library in the U.S. and one of the nation’s largest research libraries. (Images courtesy of UI Archives) When organizers of the Armour Institute in Chicago were seeking “the best man” to head their new library in 1893, they sought the advice of librarian Melvil Dewey, who created the Dewey Decimal Classification system.

His answer: “The best man in America is a woman, and she is in the next room.”

Dewey was referring to Katharine L. Sharp, who would go on to become a library pioneer at Illinois and nationwide.

Born in Elgin, Ill., in 1865, Sharp discovered her passion for libraries while working as an assistant librarian for the Scoville Institute, now the Oak Park (Ill.) Public Library. But her most formative experience occurred at the New York State Library School in Albany, where she studied under Dewey.

She established a reputation for excellence when she headed the international library exhibit at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, creating what Dewey called “the best library exhibit the world has seen.”

In 1897, UI President Andrew Draper recruited Sharp to Illinois. According to her friend, Frances Simpson, Sharp was drawn to UI because of the opportunity to head both its library and library school. No other major American academic libraries were led by a woman until well into the 1960s, according to Donald Krummel, author of the book, No Boundaries.

Sharp and her team “organized the library’s 40,000 volumes and created a reference system to support the collection,” wrote Nicholas Hopkins in The University of Illinois: Engine of Innovation. “By 1907, the Illinois library school had become a rival of Dewey’s program in Albany.”

Unfortunately, the workload at Illinois, coupled with the deaths of her brother and father in the span of a few months, took its toll on Sharp.

Consequently, she left Illinois in 1907 to work as vice president of the Lake Placid Club in New York alongside her mentor Dewey. But in 1914, she was thrown from a car and died at age 49.

In 1922, Illinois honored her with a memorial, and a plaque bearing her name hangs near the circulation desk of the main library. In addition, the American Library Association named her one of the 100 most important library leaders of the 20th century.

Sources: No Boundaries, University of Illinois Press, 2004; The University of Illinois: Engine of Innovation, University of Illinois Press, 2017; and the University of Illinois Archives.