Quad Day

Quad Day crowd, 1972 (Image courtesy of UIAA)

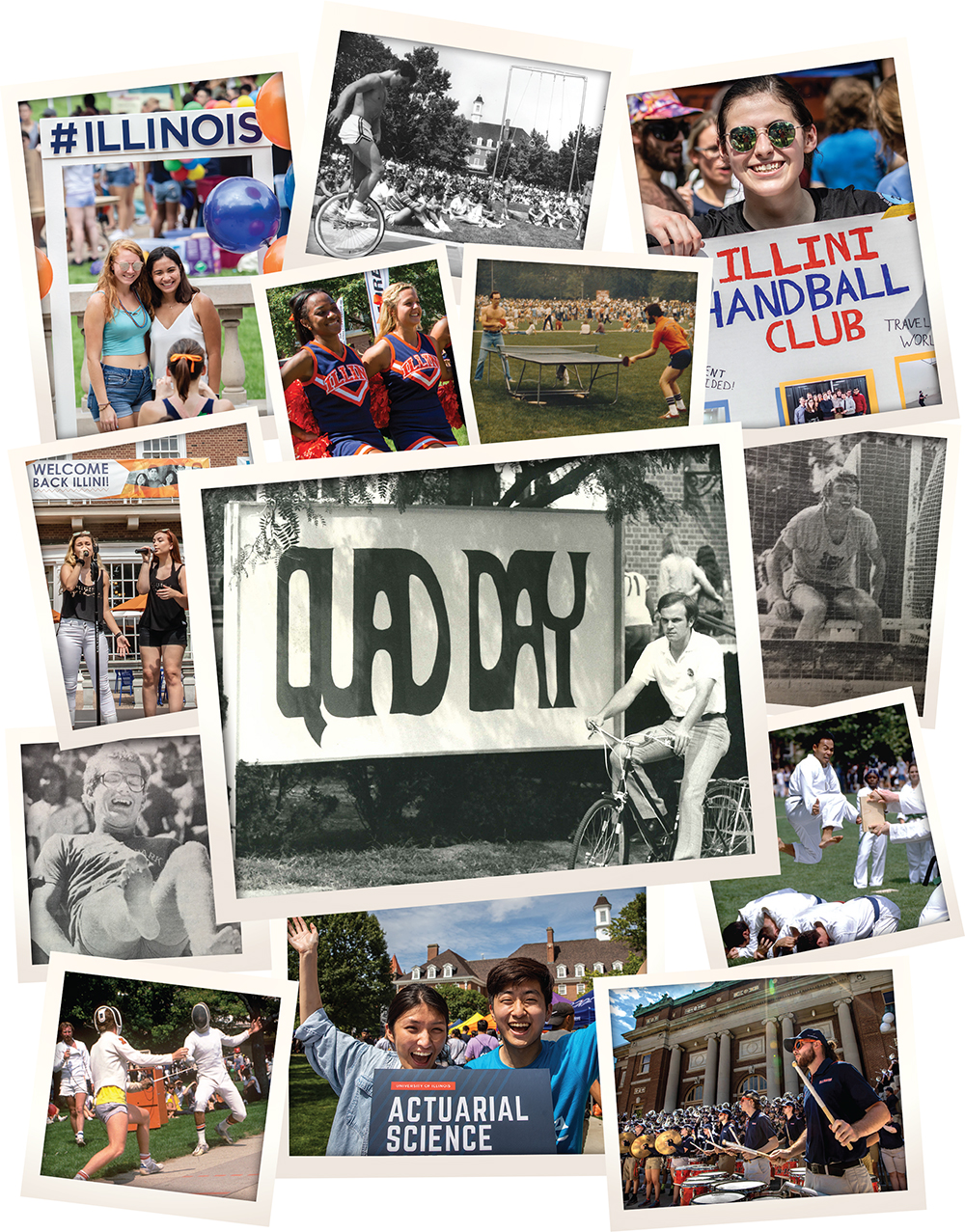

Quad Day crowd, 1972 (Image courtesy of UIAA) Quad Day. When you read those words, what comes to mind? A sea of people stretched from Altgeld to the Auditorium, browsing tables and booths? A rock band on an outdoor stage, the Quad’s buildings lit like giant lanterns, late into the night? A volleyball game on the grass, faculty versus students, with bragging rights on the line? Or maybe a hot air balloon, taking to the sky?

Ask an older or younger Illini the same question, and you’ll end up with wildly different answers—Quad Day has been many things to many people over the past 50 years.

Current students know it as an information fair that helps to kick off the school year every August—a platform for campus groups and student organizations to promote themselves and find new members, using free merchandise, elevator pitches and demonstrations.

From decade to decade, the number of booths has grown incrementally, and as a result the event today resembles an outdoor trade show, covering the entire Quad—an army of tables in formation and a mass of humanity, talking, laughing and bumping into each other, in an extrovert’s paradise and an introvert’s worst nightmare.

Once upon a time, however, Quad Day was more like a carnival than a recruitment event. Its offerings were experiences rather than flyers and free T-shirts. And its origin was born of conflict rather than connection.

From the buttery heaven of Corn on the Quad and the silliness of tricycle races to the gravity of political protests, Quad Day has hosted a variety of activities over the past 50 years. (Images courtesy of Illini Media and UIAA)

The origin of Quad Day

In the late 1960s and early ’70s, the U of I was in a state of tumult. Student protests over the Vietnam War, civil rights and corporate recruiting on campus nearly shut down the University in the spring of 1970, and by the next year, tensions between students and faculty had continued to grow, fostering a culture of distrust and disharmony. Many students viewed the faculty as “too controlling” and “defenders of the establishment,” according to Willard Broom, ’72 EMDAI, EDM ’78, while many faculty members viewed students as “long-haired hippies” who were ruining the country.

Dan Perrino, ’48 FAA, MS ’49 FAA, felt that the campus had reached a breaking point, and as dean of Student Programs and Services, he wanted to do something about it before it was too late.

“One of [my staff’s] frustrations,” Perrino once told an interviewer, “was that it seemed like what we were doing was reacting to problems rather than being proactive. And we were looking for a way to get on top of things.”

Perrino’s idea was to create an event that would bring the campus community together in a “country fair atmosphere”—relaxed, friendly, with food, music, and fun and games.

The event would be called Quad Day, and its purpose, Perrino said nearly 40 years later, was to get students and faculty “to start talking to one another and to start respecting one another”—to see each other as people, rather than fixed types battling within the hierarchy of the University and the broader society.

As well-intentioned as that may sound, many faculty members and administrators hated the idea. They viewed students as the enemy and harbored fears that a gathering of undergrads would inevitably result in a protest at the very least and possibly a riot.

At the time, the campus environment was much more conservative than it is today. Faculty and administrators were still wrapping their heads around this new brand of student, who engaged with social issues, challenged authority and wanted to be treated as an adult. Only a few years before, these same professors and administrators had been enforcing the University’s longstanding system of in loco parentis, in which the U of I acted as de facto parents for its students, setting curfews and all manner of behavioral rules and punishments. Now, they were dealing with a generation of young people who rejected that system of thinking and everything it implied. The students argued that they were old enough to be drafted into the Vietnam War and old enough to vote, and if that didn’t make them adults, nothing did. And the old guard threw up their hands in disbelief.

As Perrino and his staff—including student workers Broom and Mark Herriott, ’72 LAS—began planning the first Quad Day, they found resistance not only from the faculty, but also from many of the campus units they approached to serve as co-sponsors, such as the Illini Union. Much of that reluctance was rooted in a fear of student protests and violence, but some of it related to a strong aversion administrators felt for creating new student programs at a time when student interest in University traditions, such as Homecoming, was at an all-time low.

Some administrators also were allergic to change. Longtime University space officer Pat Flynn was aghast at the thought of students walking and sitting on the Quad’s grass, having been on campus back when no one was allowed on the grass—and here Perrino was inviting students to treat it like a village green. Flynn tried to do everything in his power to stop Quad Day in its tracks.

A wide range of clubs and groups staff Quad Day booths, including the Society of Women Engineers, Illini Voters Coalition, Students for Environmental Concerns and the Illini Homebrewers Club. (Images by L. Brian Stauffer and courtesy of UI Archives)

In short, many authority figures on campus thought the event was a bad idea—which was exactly why it needed to happen.

Unfortunately for its critics, Quad Day had one thing going for it that was awfully hard to stop: Dan Perrino. Then in the middle of his legendary 40-year career at Illinois, Perrino was a beloved figure on campus—an approachable, creative and optimistic gentleman who was well liked and respected by people of all ages, from all backgrounds. He was one of the few administrators on campus whom the students trusted. Why? He listened to them, says Broom, and he took them seriously. He often traveled around campus, talking with students, but not talking down to them. In other words, he treated them like adults.

Perrino’s involvement in Quad Day gave the event credibility and visibility with its target audience. He only hoped that enough administrators and faculty would show up to make it worthwhile.

The battle of the yo-yos

After months of planning, the date finally arrived: Sept. 10, 1971.

Perrino and his staff showed up at the Quad early that morning to set up everything they would need: a stage and sound system for live entertainment, courtesy of the Krannert Center for the Performing Arts; a volleyball net, for an epic showdown between the chancellor’s staff and the dean of students’ office; a food stand for hot dogs; and tables and chairs for students to promote their clubs and groups.

Then, like the hosts of any party, they waited for their guests to arrive.

How many guests? They had no idea what to expect.

But they would shortly learn that their hard work in promoting the event through word-of-mouth and coverage in The Daily Illini had paid off, when 7,000 students came to the Quad, ready for a good time.

Some came because Perrino and his staff had invited them, but many were there because the stories in the newspaper made it sound like it would be a total blast.

And it was.

The event started—as it would for decades—with an 11:30 a.m. concert on the Altgeld Chimes. From that auspicious beginning, students prowled the Quad’s western sidewalk, checking out the 50-odd student information booths and exhibits that stretched from the Union to the English Building—a far cry from the 600 booths of today, but an astounding turnout for a first-year event.

Over the course of the afternoon and evening, students enjoyed a wide variety of entertainment, including a performance by the Marching Illini and cheerleaders (now a decades-long tradition); a faculty/student talent show; a Hound Dog Moses concert; and folk music by the Red Herring.

But the biggest surprises for students were the performances by faculty and administrators. The much feared John Scouffas, ’66 MEDIA, chair of the University Senate Committee on Student Discipline, proved to be a marvelous opera singer. When he sang the piece “Granada” and hit its notoriously difficult high-note, “the whole audience just gasped,” said Perrino. Then Scouffas stopped singing and said, “Didn’t think I could do it, did you?” and the students erupted in applause.

Even more enlightening was the yo-yo contest—yes, yo-yo contest—in which Jack W. Peltason revealed that he was much more than the chancellor of the Urbana campus: he also had been the sixth-grade yo-yo champion of Kansas City, and he was there to defend his crown against all challengers.

“We were trying to get the students to realize that Hugh Satterlee [the dean of students] was not an ogre, and the chancellor was not a devil,” said Perrino. And for that day, and for each subsequent Quad Day, it seemed to work, at least temporarily.

Chancellor Peltason’s yo-yo heroics would become a prominent feature of the earliest Quad Days, but he would win only that first year. Thereafter, he met a buzz saw in the form of Fine + Applied Arts Dean Jack McKenzie, ’54 FAA, who made it his mission to outdo Peltason in every aspect of the competition. He had cooler yo-yos, flashier tricks and a flair for the dramatic. One year, he showed up wearing a cape and a red Cyrano de Bergerac hat—beplumed with a white feather—and made his entrance carried in on a throne, like a Roman emperor, the Marching Illini leading him in from the Undergraduate Library to the stage at the Union.

After losing to McKenzie two years in a row, the chancellor archly demanded an investigation “under International Yo-yo rule 3a,” to no avail. The next year, 1974, the two Jacks were soundly defeated by a surprise contestant, counseling psychology Ph.D. candidate John T. Hardin, edm ’73, PHD ’76 ED, and both subsequently retired from public competition.

A chancellor and a dean bickering in public about their yo-yo rivalry: that pretty well captured the nature of those earliest Quad Days—borderline absurd, totally unpredictable, but always fun.

So free and easy was the atmosphere of the first year, in fact, that an impromptu, entirely ropeless, imaginary tug-of-war started in the crowd. “Two were on one end of the imaginary rope and two on the other, and they kept pulling and pulling,” Perrino recalled. “And other students were getting behind those students. So, ultimately, there was a long line of people participating…And they pulled them all the way up on the stage” and continued the tug-of-war there.

“What it was indicating was that we were working together…cooperating with one another,” Perrino said, “because I am sure [the students and faculty] didn’t know who was in each line, and it didn’t matter.”

Perrino’s objective, to humanize students and faculty for each other through fun and games, was a great success.

Corn on the Quad

Over the next 50 years, Quad Day would develop into a cherished annual tradition, changing with the times, students’ interests and organizers’ whims. As the event grew, it would bring together not only students and faculty, but also campus units that had rarely, if ever, collaborated. After the Illini Union and Campus Recreation agreed to assume control in the mid ’70s, a wide variety of groups began helping out, including cultural houses such as La Casa Cultural Latina; student honorary societies; the Alumni Association; the Interfraternity and Panhellenic Councils; the Dad’s Association; and many others.

Although the event changed from year to year, the ’70s through the mid ’90s were known for their abundance of activities. The yo-yo contests and volleyball games of the early years served as a jumping-off point for what followed. There were contests in Frisbee accuracy, limbo dancing, bubble gum-blowing, balloon bursting, balloon shaving, kite flying and more. There was face painting, outdoor bowling, karaoke and a water balloon toss, which turned into a water balloon fight in 1981, amid an afternoon rainstorm. There were rock concerts sponsored by Star Course; jazz by Perrino’s Medicare 7, 8 or 9 band; and soul music by the Bruce D. Nesbitt African American Cultural Center.

Several activities became Quad Day institutions and appeared on the schedule for a decade or more—the tricycle race, slip ’n’ slide, slam dunk competition, home run derby, dunk tank and paper airplane flying contest became as common as the information booths that lined the sidewalks.

One of the best-loved Quad Day traditions was “Corn on the Quad,” a sweet corn boil that had students salivating for days in advance. During the ’70s and ’80s, the Illini Guides—masters of Move-In Day and corn chefs extraordinaire—used a 1923 A.D. Baker Co. steam engine to boil more than 100,000 ears. Students initially paid 10 cents, then used 25-cent, wooden “Quadder Dollars” and, later, 50-cent Quad Day Tokens to buy their corn. Former I-Guide Jim Schlueter, ’80 MEDIA, recalls that after hours of cooking and serving he was covered in melted butter. “I could’ve slid back to my dorm!” he says.

Not every Quad Day feature became an institution like Corn on the Quad. Most made a brief appearance, proved unpopular or just plain strange, and ended after a year or two. Among the messiest was the cotton ball carry, which required students to smear Vaseline on their noses, attach a cotton ball, and carry as many as possible to a five-gallon bucket. No hands allowed!

Other Quad Day activities were definitely products of their time, such as “Operation Identification,” a University Police program to engrave bicycles and other possessions with students’ social security numbers. Yes, you read that correctly. The argument, which might have made sense in a cash-and-checks world but seems truly insane today, was that the SSNs plastered on everyone’s stuff would help to deter theft and recover stolen goods. Stolen identities—the least of their concerns.

Governor Dan Walker makes an appearance

Yo-yos and dunk tanks to the contrary, Quad Day was not all fun and games.

In its early years, the event served as a platform for civil discussion between students and authority figures from outside the University, including Illinois politicians and office seekers, who made a point of stopping by to meet the newest batch of eligible voters.

State legislators talked with undergrads about social issues, University Trustees played Quad Day games and, at a time when the Board of Trustees was still elected by a state-wide ballot, candidates showed up to canvass for students’ votes.

In 1975, even Illinois Gov. Dan Walker made an appearance, taking part in a Frisbee accuracy contest and eating some Corn on the Quad.

Throughout its history, Quad Day has also provided an opportunity for students’ voices to be heard on a wider scale, and students have taken advantage of it. Political organizations have been a consistent presence over the past 50 years, whether they staffed a booth, like the College Democrats and College Republicans; made public addresses in the Quad’s Free Speech Area; or took a less subtle approach, like the Divest Now Coalition, which, in 1985, staged a mock funeral march—complete with coffins and signs—to protest the University’s investments in companies that traded with South Africa, as part of a larger effort to end that country’s system of apartheid.

Quad Day demonstrations have included martial arts displays, dance competitions and mock battles by live-action role players. (Images courtesy of Illini Madia and UI Public Affairs)

Martial arts demos

Beyond the booths, concerts, food stands and games, another defining feature of Quad Day has been its (non-political) demonstrations by student clubs and sports teams.

Some have stood the test of time. Martial arts demos—especially Tae Kwon Do and karate—have been a staple since the ’70s, and since the ’90s have included such lesser known forms as ving tsun, aikido and kuk sool won. Men’s and women’s gymnastics have been mainstays since the ’80s, while dance teams have been a fixture in recent decades.

While those have become perennial attractions, others captured the zeitgeist, lasted for a few years, then faded away.

The ’70s gave us medieval combat demonstrations by the Society for Creative Anachronism; a “campus celebrity” relay race that starred faculty and administrators; and hot air balloons launched from the Quad, including one that crash-landed shortly after takeoff, recalls Esther Muhr, MA ’78 FAA.

The ’80s produced unicyclers, jugglers, torch throwers and other attractions that would have been right at home in a circus, along with a host of events that may have been better suited for a track meet: the javelin throw, shot put, and—yes—Olympic shooting sports. (We assure you, no one was harmed in the making of that Quad Day.)

In the ’90s, attendees enjoyed swing dancers, a cappella groups, improv troupes, music from the Brazilian Student Association and a drum performance from Hock-San Chinese Lion Dance.

In the 21st century, the space for demonstrations has been reduced in favor of adding more information booths, and today only the popular holdovers—martial arts, gymnastics and dance teams—remain.

The University’s cultural houses and country-specific student groups use their Quad Day booths to teach the University community about their traditions and to give their compatriots a taste of home. (Images courtesy of UI Public Affairs and Illini Media)

Making new friends, meeting future spouses

During its first two decades, Quad Day didn’t venture far from its peacemaking, country fair origins. Gradually, however, the event became less zany. Many of the activities that gave the day a certain looney-tunes joie de vivre began to be phased out, as organizers expanded the number of booths. Gone were the tricycle races, slam dunk competition, slip ‘n’ slide, paper airplane flying contest and other gonzo games.

In the ’90s, organizers completed a years-long transition of the event’s purpose, from an information/fun fair to a dedicated recruitment day for student organizations to find new members and for campus units, such as cultural houses, to inform students about their programs and services.

For Generation X, Quad Day became a bit “like a pre-Harry Potter Sorting Hat,” says Julie Kimmell, ’94 MEDIA. “I remember [being] a freshman from a very small-town high school, and just looking at the people behind the tables and thinking, ‘Hmm, do these look like my people?’”

Some students had better luck finding their people at Quad Day than others. Maria Knight, ’94 ED, met her husband, Jason Knight, ’94 LAS, when they were both working at the I-Guides booth. “We hit it off right away,” she says, “and I remember one of the fun activities we did was a watermelon seed spitting contest. Neither of us won, but we had a good time trying.” By day’s end, Jason was Maria’s date for that evening’s Dennis Miller comedy show at Assembly Hall—one of the free events offered during New Student Week. That night, after the show, he held her hand when they walked home, “and the rest is history,” Maria says. “We have now been married for 29 years, and we still enjoy watermelon!”

While not everyone meets their future spouse at Quad Day, an untold number of Illinois alumni have met lifelong friends among the tables and booths.

Quad Day is a place where you can “meet people you would like to know and make the campus seem a little bit smaller,” says Michael Guilfoyle, ’02 LAS. As a senior, Guilfoyle ran the Quad Day booth for Simpsonica, a club devoted to The Simpsons TV series. He had started the club his junior year on a lark, taking advantage of the freedom U of I students have to create an organization for nearly any subject or area of interest. To his surprise, the group’s membership grew quickly, and in no time Simpsonica was a serious club, sponsoring not only Sunday night viewing parties for new episodes, but also a monthly forum “to discuss the show and its impact on society.”

Quad Day has served as a way for Simpsonica and many other organizations to find like-minded folks who want to talk about television shows, practice martial arts or yoga, book rock concerts, play paintball, knit, organize political protests, build racecars and just about anything else you can imagine, whether deadly serious or anything but.

Thousands of student organizations have existed at the U of I over the past 150 years, and this small sampling will give you an idea of their diversity: Falling Illini, for skydiving fanatics; October Lovers, with T-shirts in auburn and orange; Capture the Flag Enthusiasts; Club Kramerica, for devotees of Seinfeld; PRIDE, for LGBTQ+ students and their allies; Fish Lovers Union (which would be more accurately named “Fish Eaters Union”); and The Club That Must Not Be Named, for Harry Potter fans.

Those organizations and more—including Greek-letter chapters, churches and local non-profits—staff Quad Day tables and booths, handing out free merchandise with hopes of attracting new members and volunteers. Although most groups dispense standard fare—pamphlets, flyers, T-shirts, hats, coin purses, key chains, pens, pins, chip clips and the like—others put a unique spin on their collateral. The Physics Society, for example, has been known to distribute flyers straight from a bucket of liquid nitrogen, while the Horticulture Club gives out potted plants. Every year, organizations find bold and purposeful ways to stand out from the crowd.

Quad Day carries on

As Quad Day continued to grow in the early 2000s, many students began to view the event as an overwhelming, crowded, hot, sweaty, humidity trap that was best left to freshmen who were trying to find their way into campus life.

Student journalists in The Daily Illini helped to reinforce that stance, publishing opinion pieces year after year that urged undergrads to spend their day somewhere else, doing something more useful with their time. And if students absolutely had to go to Quad Day—horror of horrors—these ink-stained upperclassmen offered advice on how to survive it, in stories with titles such as “How to Say ‘No’ at Quad Day” and “You Don’t Have to Join Everything.”

Still, other DI columnists provided sound advice about how to get the most out of Quad Day: show up early; go with a friend; watch the Marching Illini; bring a bag; bring water; wear comfortable clothes (especially comfy shoes); and pack an umbrella.

No matter which advice they followed, students were sure to form opinions and expectations about the event—that is, until last year, when all expectations went out the window.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic made it impossible to host a traditional Quad Day. The event’s organizer, the Student Success and Engagement Office, was left with a choice: cancel and begin planning for 2021, or host a virtual edition, like so many other events the world over. They opted for the virtual experience, with interactive components that tried to replicate the smorgasbord of clubs and groups that would have staffed tables on the Quad. It was a tall order for the organizers—especially for their very first Quad Day, having taken over from the Illini Union right after the pandemic started—but the website they created was straightforward and well-designed, and the event was a success.

This year, Quad Day was back in person, though it was far from business as usual. Social distancing measures were strictly enforced, and larger booth sizes helped to disperse the crowd.

What will the future hold? It’s anyone’s guess. But alumni can rest assured that Quad Day will continue to be a vital part of the U of I experience, welcoming students new and old each fall, as they adjust to life on campus—helping them to discover their independence, explore their interests, and learn who they are and what they value.

Learn more about the events that led to the first Quad Day in Illinois Alumni magazine.