Co-Education

Alethenai Class, 1871 (Image courtesy of UI Archives)

Alethenai Class, 1871 (Image courtesy of UI Archives) In her later years, Frances Potter Reynolds, Class of 1874, recalled the day in 1870 when the Illinois Industrial University’s Board of Trustees voted to admit women as students. Unlike the 14 other “young ladies” who would enroll that fall after hearing the news from family, neighbors or the local newspaper, the 17-year-old Reynolds witnessed the Trustees’ vote in person—in a manner of speaking. Call her a fly on a nearby wall.

For Reynolds, unlike the other young women, was already on campus. Her parents were on the original staff of the school that would eventually become the University of Illinois, responsible for the first students’ room and board in the “Elephant,” a five-story red brick structure that was the only campus building. The family lived in an apartment on the second floor, across the hall from the small library where the Trustees held their meetings. That Au- gust day, Reynolds and her mother were in their apartment, politely eaves- dropping on the proceedings, eager to learn the Board’s decision following nearly two years of sporadic debate and failed votes. There were speeches for and against, lively discussion, applause and even hissing. At one point, Reynolds heard a Trustee bark, “I say, if a girl wants to build a wagon, let her build a wagon!” Finally, the Trustees took their vote: deadlocked at 4-4.

The tie-breaking vote was left to the University’s first regent (the office later known as president), John Milton Gregory. A Baptist minister and former president of Kalamazoo College in Michigan, Gregory was not in favor of co-educating women and men at the same institution and had spoken publicly to that effect in 1868 at a local farmers’ convention, where Mrs. Tracey Cutler proposed that women be admitted to the University. Gregory argued that the school did not have adequate facilities to educate and house both men and women. A product of his era, he further worried that the admittance of women would lower the school’s standards of scholarship.

Top, L-R: Frances Potter Reynolds; The “Elephant,” where Illinois’ first women students attended classes; and John Milton Gregory, the University’s first regent (president). Bottom: An 1873 flyer the University distributed throughout Illinois to attract female students. (Images courtesy of UI Archives)

However, he also was a proponent of liberal higher education and believed that it was his moral duty to provide students with a curriculum that would prepare them for living more fulfilling lives. When the time came for the final vote, he cast in the women’s favor.

“I know it must have been a trial to vote as he did, against his inclinations,” Reynolds wrote nearly 50 years later. “[But] his prophetic sense told him he must do it in order to help a real advance movement.”

Less than a month later, the first group of “young ladies” arrived at the Elephant. Many came from the surrounding counties. All of them were white. They found themselves on a two-year-old campus whose bleak landscape had been somewhat brightened by the first male students. Its 13 acres (excluding 600 acres of agricultural grounds) were marked by young trees, flowers and shrubs, newly planted grass, and board and gravel walks that helped students circumvent the mud—a prevalent feature of the one-time swamp.

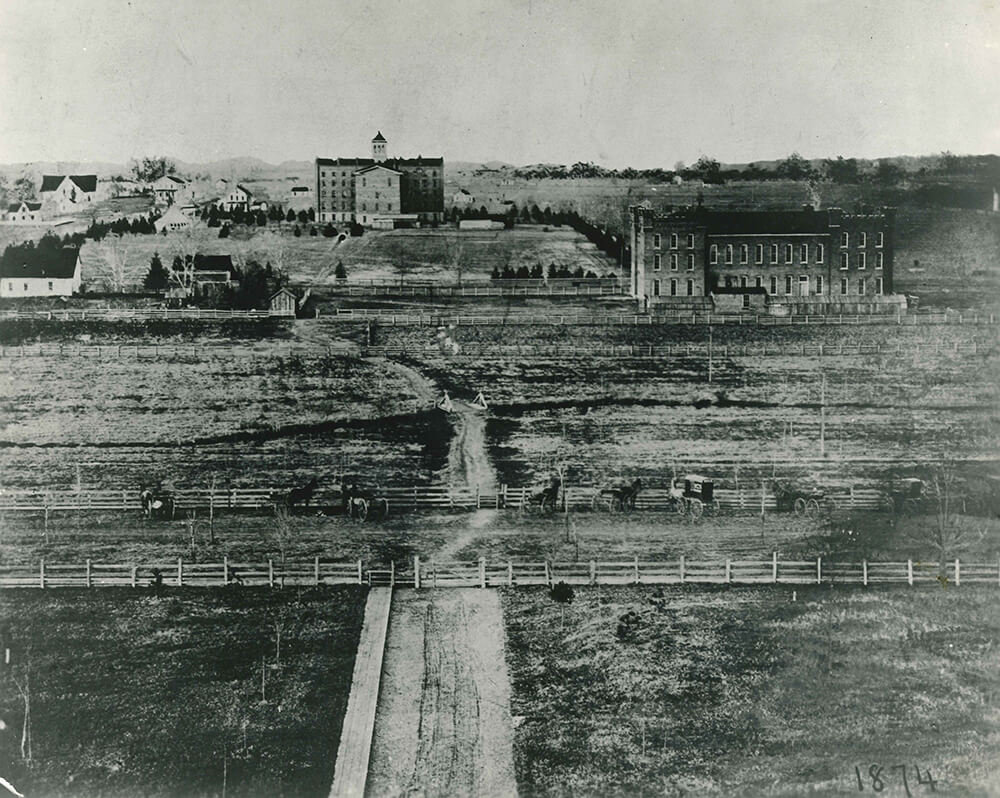

Taken from an upper-story window of the new University Hall (near the present site of the Illini Union), this 1874 photo shows the campus, from south to north: Green Street, Boneyard Creek, and Springfield Avenue, our first armory building on the right, and the Elephant at the top. (Image courtesy of UI Archives)

The first women students entered a University that was much different from the one we know today. At the end of the 1869-70 school year, it was an enclave of 180 undergraduates who took courses in five general areas: agriculture, civil engineering, mechanical engineering, military science and “the elective,” which covered every- thing else, from chemistry and math to history, literature and languages.

Students could enroll at any point during the year, were not granted degrees and rarely completed four years of study. Outside of their courses, there were few clubs or organized activities for them to enjoy, and the concept of Campustown, with its bars, restaurants and other student hangouts, did not exist. The students’ lives were regimented by rules and regulations that might astound the Class of 2020: daily religious services in the University chapel; bans on gambling, drinking alcohol and visiting pool halls; and edicts against “whistling, singing, dancing or making any unnecessary noise during the time of study and quietness”—infractions that were

punishable by fines. The men had compulsory military drill in the University Battalion. The women had restrictions on their social lives, with outings allowed only on weekends, monitored by chaperones and subject to a strict curfew of midnight.

Breaking Down the Doors of Higher Education

In “The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820-1860,” historian Barbara Welter writes that the prescribed traits for American women in the mid-19th century were “piety, purity, submissiveness and domesticity.” College attendance was uncommon; in fact, women were not permitted to enroll in any U.S. university until Oberlin College (Ohio) became co-educational in 1837. In the decades that followed, colleges for women began to open along the Eastern seaboard. Many were established to train teachers, while others were the female counterparts to what would become known as the Ivy League.

Co-education at the college level was rare and remained so until the Civil War, when the declining numbers of male students motivated some private institutions to change their policies, admitting tuition-paying women for the first time. Following the Civil War, public universities (and particularly land-grant schools) led the charge in admitting women to institutions that were previously open only to men. Illinois was one of the first.

From the beginning, women at Illinois received the same educational opportunities as men (excluding mandatory courses in military science). They could study anything they wished. As with the male students, it was uncommon for them to finish four years of schooling; many of the first women on campus completed a year, give or take a semester, and then left to teach in rural schools throughout Illinois and across the Midwest. Of the original 15 women admitted to Illinois Industrial University, two graduated in 1874.

By the end of 1871, Regent Gregory had completely changed his mind about the co-education of men and women and became one of his female students’ most vocal supporters. He found them to be model students in his history courses, and he was pleasantly surprised by their positive impact on the campus culture.

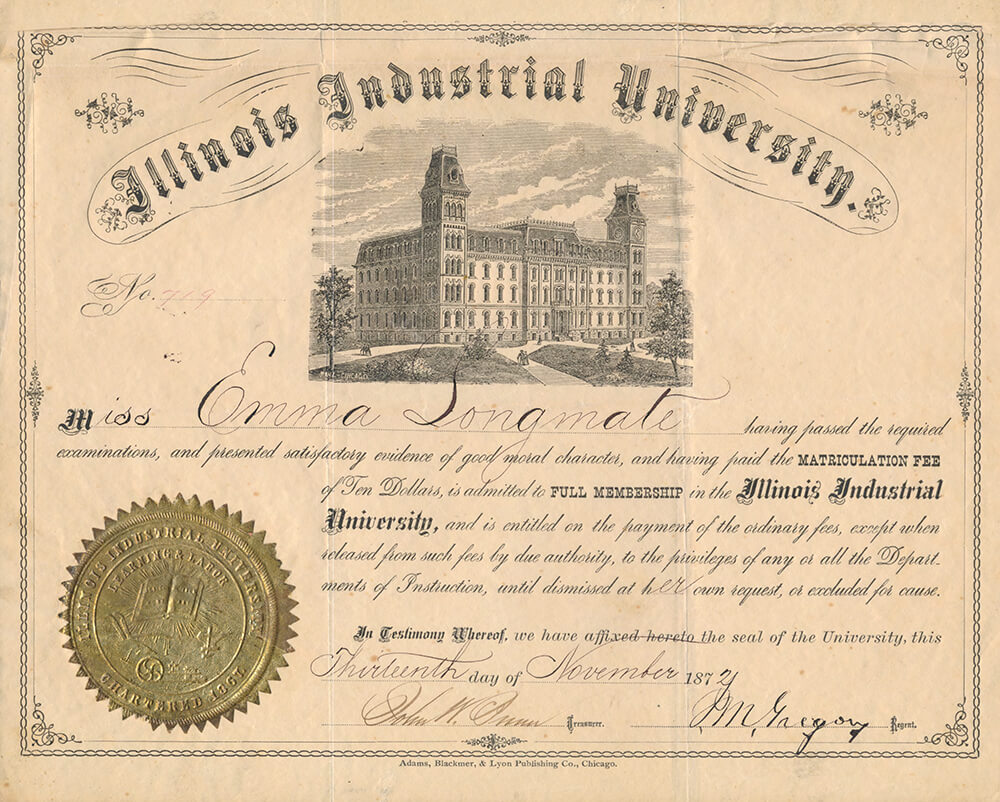

Emma Longstreet’s Illinois Industrial University entrance certificate, 1872. (Image courtesy of UI Archives)

His change in viewpoint was so profound that he convinced the president of Cornell University, Andrew D. White, to expand Cornell’s admission of women, reporting, “I find that the standard of scholarship is raised [since women entered the University]. I do not know that the health of any girl has suffered by study, and no breach of morals has come to our notice, while we observe that the influence [on the male students] is refining and beneficial.” Gregory obviously hadn’t heard about the men interrupting the women’s club meetings by loudly playing their horns and climbing onto the Elephant’s roof to spy on them in their top-floor meeting room, “at the imminent hazard of life and limb,” as one female student described it.

In 1872, Regent Gregory announced plans to create an academic unit specifically for women students. Just as military science was considered a department for men, the new School of Domestic Science would be for women, to “provide a full course of instruction in the arts of the household, and the sciences relating thereto.” Although “home economics” programs had previously existed at other institutions, they were “of the cooking- and sewing-school variety,” according to University historian Winton Solberg. Gregory was not talking about a cooking and sewing school. Rather, he envisioned a liberal education for women students—the same liberal education he envisioned for all Illinois students—which was considered a radical idea for the times.

Louisa Allen Gregory, leader of the University’s School of Domestic Science and Art. (Image courtesy of UI Archives)

Organizing the School of Domestic Science took longer than anticipated because of the state’s financial struggles and reduced appropriations to the University. In 1874, two years after his announcement, Regent Gregory hired a 22-year-old graduate of Illinois State Normal University to head the new program, and later, to serve as “preceptress,” a semi-official dean of women. Louisa C. Allen, namesake of the University’s Allen Hall, was a spitfire, visionary, disciplinarian, dynamo, known to her students as “The Lady Principal.” She was straightforward in comportment, did not tolerate impropriety and ultimately earned the respect of both her students and her colleagues.

Allen came to the University with little professional experience but strongly defined views on women’s higher education, and Gregory allowed her to create a school that suited her “own tastes.” In planning the School of Domestic Science, she spent the summer of 1874 (and every summer thereafter) studying in Europe, meeting with scientists at Ivy League schools, visiting women’s colleges in New England, and developing a system of instruction based on Catherine Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s The American Woman’s Home, a popular 1869 book that promoted scientific practices in homemaking.

A quarter-century after Louisa Allen came to Illinois, Isabel Bevier built on the legacy of domestic science with “household science,” a groundbreaking University program that sought to improve the health and well-being of families through applying quantitative, scientific practices. (Image courtesy of Illio 1907)

Putting the “Science” in “Domestic Science”

Allen’s mission statement for the School of Domestic Science and Art (as it was ultimately known) appeared in the University’s 1875 Catalogue and Circular. Reinforcing the societal expectations of women at the time, while also striving to redefine those expectations, it read:

“This school proceeds upon the assumption that the house-keeper needs education as much as the house- builder, the nurse as well as the physician, the leaders of society as surely as the leaders of senates, the mother as much as the father, the woman as well as the man. We discard the old and absurd notion that education is a necessity to man, but only an ornament to woman. If ignorance is a weakness and a disaster in the places of business where the income is won, it is equally so in the places of living, where the income is expended. If science can aid agriculture and the mechanic arts to use more successfully nature’s forces and to increase the amount and value of their products, it can equally aid the house-keeper in the finer and more complicated use of those forces and agencies, in the home where winter is to be changed into genial summer by artificial fires and darkness into day by costly illumination; where the raw products of the fields are to be trans- formed into sweet and wholesome food by a chemistry finer than that of soils, and the products of a hundred manufactories are to be put to their final uses for the health and happiness of life.

“It is the aim of the School to give to earnest and capable young women an education, not lacking in refinement, but which shall fit them for their great duties and trusts, making them the equals of their educated husbands and associates, and enabling them to bring the aids of science and culture to the all important labors and vocations of womanhood.

“The purpose is to provide a full course of instruction in the arts of the household, and the sciences relating thereto. No industry is more import- ant to human happiness and well-being than that which makes the home. And this industry involves principles of science, as many and as profound as those which control any other human employment. It includes the architecture of the dwelling house, with the laws of heating and ventilation; the principles of physiology and hygiene, as applied to the sick and the well; the nature, uses, preservation and preparation of animal and vegetable food, for the healthful and for invalids; the chemistry of cooking; the uses, construction, material and hygiene, of dress; the principles of taste as applied to ornamentation, furniture, clothing and landscapes; horticulture and culture of both house and garden plants; the laws of markets; the usages of society and the laws of etiquette and social life.”

Women who elected to study domestic science selected from a wide range of courses, including chem- istry, advanced botany, physiology, American and British literature, entomology, zoology, German, French, architecture, mental science, freehand drawing, woodcarving, landscape gardening, political economy and house- hold science. They also were offered a great span of history options: ancient, medieval, modern, constitutional and the history of civilization. Among the small faculty who taught these courses were nascent professors who would become internationally respected in their fields, including the architect Nathan Ricker and botanist Thomas J. Burrill.

While the School of Domestic Science and Art was created specifically for female students, enrollment was not a requirement. Women at Illinois remained free to pursue any course of study they desired, per Regent Gregory’s directive. (And they did! Mary Page, for example, became the first woman in the U.S. to receive a degree in architecture, in 1879.)

Gregory genuinely tried to provide equal opportunities for men and women students, and introduced new courses in music and the fine arts at the women’s request. However, the Board of Trustees was less progressive and viewed such courses as outside the scope of the University’s mission as they interpreted it—to provide education in agriculture and “the mechanic arts” (i.e., engineering). As a result, the Board required students (most of whom were women) to pay additional fees for music instruction.

Finding a Home Away from Home

By the spring of 1871, 24 women were enrolled at the University, out of 278 students. Like their male counterparts, they studied, attended classes and held meetings in the Elephant. However, unlike the men, they were not allowed to live there. The Trustees had agreed to admit women whose parents could find “proper homes” for them in Champaign or Urbana. Local women (“townies,” as we would now call them) lived with their families, while others found rooms in private dwellings. Regent Gregory soon added to their options by using his own money to provide two women’s boarding houses. He hired a matron with boarding school experience to manage the proper- ties and charged his tenants $3 per week in rent. The women brought their own furnishings and shared the houses’ parlors and laundry facilities.

After two years, the University invested in a new Ladies’ Boarding House, capable of housing 20-25 students. According to a promotional flyer the University sent to county superintendents of education throughout Illinois, the new boarding house was meant “to furnish a pleasant home and to secure the students cheap board which, under the care of an intelligent Matron and Instructress, the pupils kept house and received instruction in Domes- tic Science.” Like Regent Gregory’s boarding houses, unfurnished rooms were $3 per week. However, for 50 cents more, students received a “bed- stead, wardrobe, washstand, table, two chairs and stove.” And, for those who wanted the finest accommodations available, the princely sum of $4 per week got you a “fully furnished” room—explanation not provided.

By the time the first women students graduated in 1874, the University had bought the house next door—also housing 20-25 students—and given the complex a new name: the Young Ladies’ Boarding Hall. Prices remained the same.

While Illinois’ earliest women students attended classes in University Hall and their boarding houses, the next generation would have their own building—the Woman’s Building (now the English Building)—thanks to the efforts of Trustees Lucy Flower and Julia Holmes Smith and University President Andrew Sloan Draper. (Image courtesy of Illio 1909)

Louisa Allen and the Calisthenics Crusade

One of the great scandals of the University’s early years centered on physical education. Louisa Allen believed that an education should include both mental and physical components to provide students with “sound minds in sound bodies.” To that end, she introduced a compulsory calisthenics program for women on campus, consisting of dumbbell and wand exercises and lectures on personal hygiene.

While seemingly innocuous today, Allen’s program caused a furor among parents, physicians, Trustees and the general public, who worried that the women’s exercise clothes would be indecent and that physical activity would compromise their health. (For a good laugh, see the above photo.) More than a third of the women were excused from the exercises following their parents’ pro- tests. However, Regent Gregory de- fended the program, and together, he and Allen hatched a plan to change their critics’ minds: They would host a public calisthenics exhibition and invite their naysayers to see the class in action. Of course, it worked. The critics became supporters, and the Board of Trustees endorsed the pro- gram. For the rest of Allen’s tenure, calisthenics exhibitions became popular attractions at University events.

Gregory and Allen eventually married in 1879 and left the University the following year, thus ending the tenure of the school’s first regent—a period marked by bitter argument about the institution’s mission between the progressively minded Gregory and the Trustees, the state legislature and the general public, who favored a curriculum firmly rooted in agriculture and the mechanic arts. Through the continued efforts of his like-minded successors, Gregory’s vision for Illinois to become a touchstone of liberal, public higher education ultimately came to pass, and today, he is buried on the Illinois campus, between Altgeld Hall and the Henry Administration Building.

Clockwise, from top: The offspring of Louisa Allen’s calisthenics program: The women’s gymnasium, 1897; “Ladies’ Gym,” ca. 1870s, 1901 Illio and “Basket-Ball Team,” 1899 Illio. (Images courtesy of Illios)

Creating a Culture

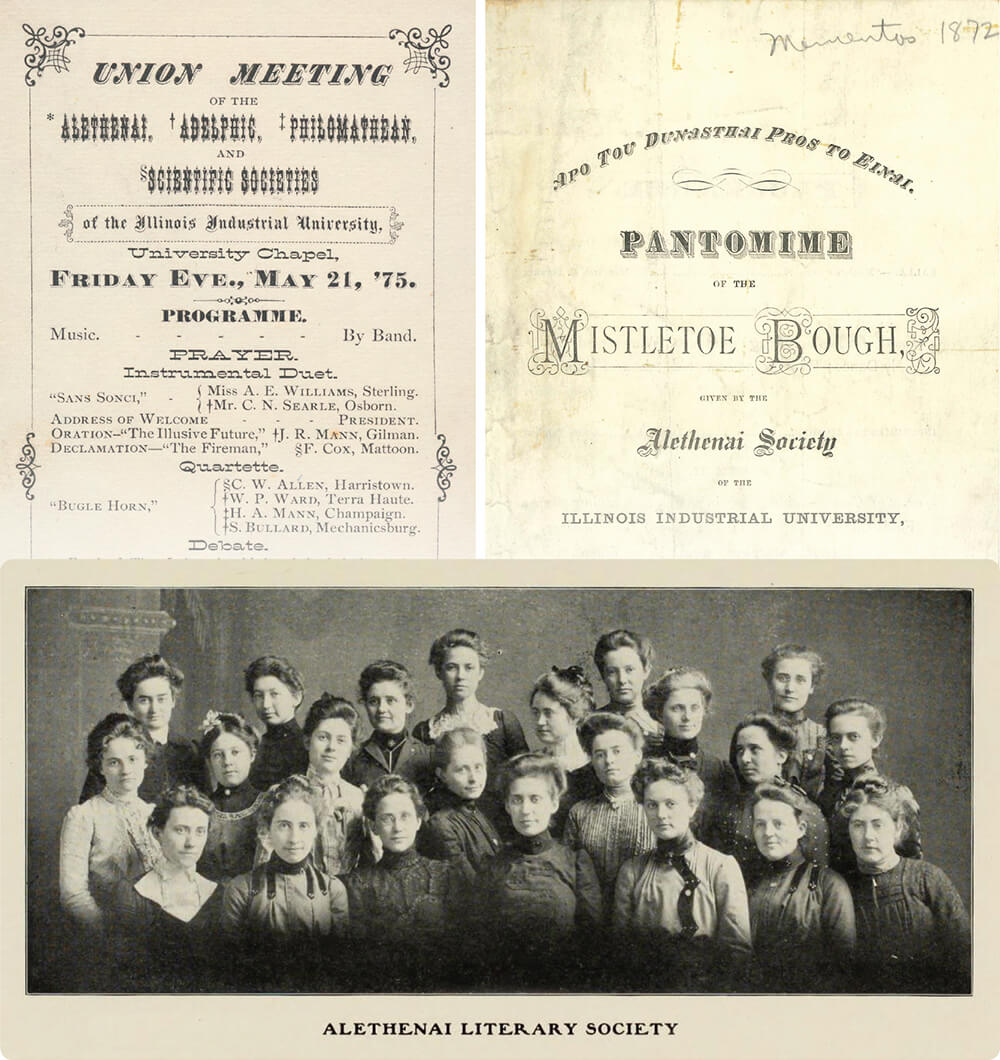

Outside of their studies, Illinois’ early women students became active in campus life, such as it existed in the 1870s. After attempting to join the men’s literary societies—the most exclusive social clubs on campus— and being refused membership, the women started their own organization in 1871, the Alethenai literary society. Taking the Greek word for “the truthful ones,” the Alethenai quickly became a source of camaraderie and intellectual solidarity for its members, a weekly cultural salon in a landscape that was sorely in need of culture. Its motto was “Apo ton dunaethai, pros to einai,” which translates to, “From the woman to the being.”

Early women students made their mark on the campus culture, founding literary, music and religious organizations. Top left: “Union Meeting” of the campus literary societies poster, 1875. Top right: The Mistletoe Bough, performed Dec., 5-6 1872. Bottom: Alethenai Literary Society, 1902 Illio. (Images courtesy of UI Archives and Illios)

The Alethenai held oratorical contests and debates, played music, hosted touring lecturers and musicians, and read aloud their own es- says about history, art, science and the issues of the day. The club gave its members a platform to speak, to express themselves in ways that might not have been possible back home, and supplied them with the encouragement to be leaders outside the walls of the Alethenai meeting room. To that end, the Alethenai staged what might have been the first ticketed theatrical performance in Champaign-Urbana, The Mistletoe Bough, performed Dec. 5-6, 1872.

The Alethenai next formed a semi-annual “Union Meeting” of all the campus literary societies, which allowed men and women to listen to each other articulate their ideas and feelings in ways that were more thoughtful, deliberate and revelatory than in everyday life. According to The Illini newspaper (now The Daily Illini), the women’s orations during these meetings were “fully equal, if not superior, to the young men.”

While the University’s early women students were certainly restricted and oppressed by the firm regulation of their social lives and behavior, they showed an indomitable spirit in their approach toward extracurricular activities that made them a vital, energetic minority who completely changed the social and cultural fabric of the campus.

If the women students wanted an opportunity and it was denied them, they created a new one. From the initial spark of the Alethenai, they founded music societies and one of the nation’s first campus chapter of the Young Women’s Christian Association (established in 1873 and later revived, permanently, in 1884). In the decades that followed, they would found the campus’ first sororities, as well as the University’s first basketball team—a women’s team—in 1897.

The first female students became leaders and participants in virtually every facet of campus life that was open to them. They served as officers in College Government; editors and writers for the University’s first student-run publication, The Student (1871-73), and later, The Illini; and speakers at important University events. Alice Cheever Bryan, who, along with Reynolds, was the only other woman to graduate in the Class of 1874, was a prime example of women in leadership. She was vice president of the student government, delivered an address at Founders’ Day in 1874, spoke at Senior Class Day and served as the Class of 1874’s representative to the Alumni Association. After graduation, she studied at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston and went on to a teaching career in Peoria, Ill. During her time on campus, she was not an outlier, but only one example of a woman doing her part to create a campus where co-education could thrive.

Setting a Precedent

The admission of women to Illinois ultimately had a profound effect on the institution’s future development. Women students’ interest in the liberal arts; the addition of new “women-friendly” courses in fine arts, music, languages and domestic science; and the positive changes in student life wrought by co-education helped to broaden the University’s academic scope and fuel the aspirations of its administration. In the school’s early years, when the state legislature, several Trustees and many Illinoisans felt strongly that the Illinois Industrial University should remain an industrial school limited to education in agriculture and the mechanic arts, women students played an important role by showing that the University could be so much more. They proved, through their determination to attend college and their success once they got there, that Illinois could be a source of both practical and liberal education, regardless of one’s gender.

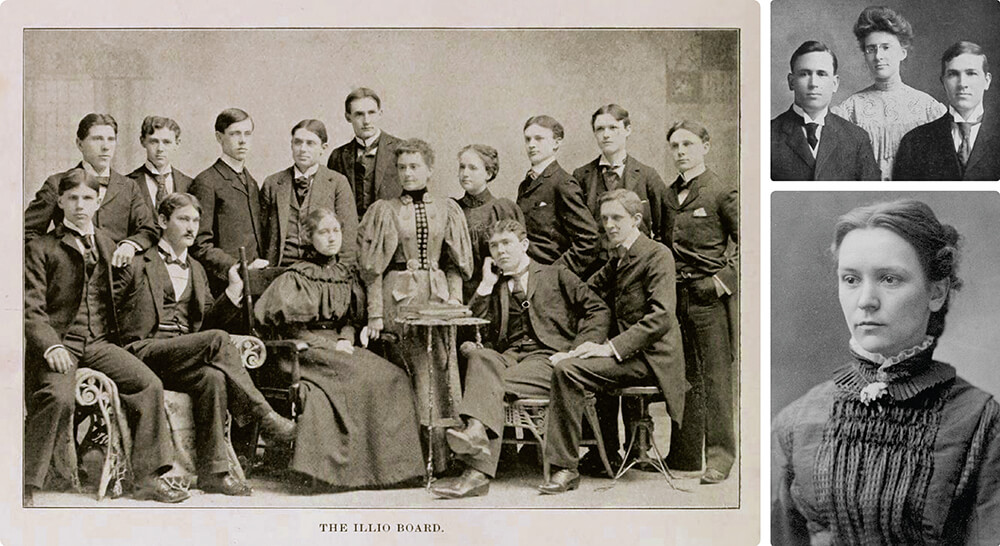

Bottom right: Illinois’ early female students proved their mettle and broke new academic ground, including Mary Page, the first woman to earn an architecture degree in the U.S. (Image courtesy of UI Archives) The next generation followed in their footsteps, taking leadership positions with student publications (left, Illio Board, 1897) and demonstrating their oratorical skills (top right, Debate team, 1908 Illio).

Within 20 years of their arrival on campus, the University admitted its first Native American, African American, Latinx and international students, and in 1885, the Illinois Industrial University changed its name to the University of Illinois, a more accurate reflection of its growing curriculum and a mission statement for what the institution would become. Those measures of progress might have taken much longer if it hadn’t been for Illinois’ early adoption of co-education and the proven success of its first women students.

A century-and-a-half later, women continue to find a home at Illinois. Some study education and follow the path of the earliest women students, becoming teachers of the next generation; some pursue fields that weren’t open to women in the 19th century, such as engineering, the hard sciences and law; and some transform the world in other ways, by charting paths in areas that did not exist when Illinois was new, such as computer science and nanotechnology. Whatever their field, the University’s women students and alumnae stand on the shoulders of those original 15 “young ladies” and those who fol- lowed, with each generation enjoying educational and professional opportunities that were not open to their predecessors. With that in mind, we can’t wait to see what Illinois women will achieve in the next 150 years.