Getting To The Promised Land

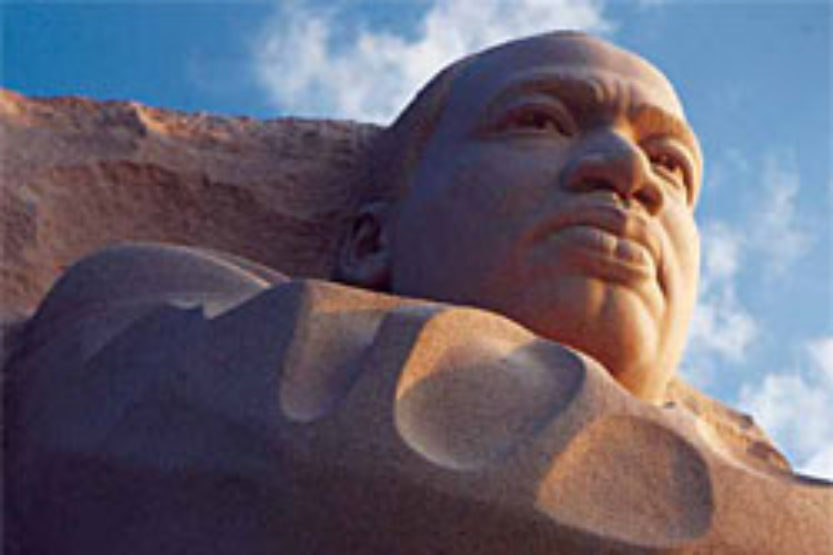

The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial

(Image courtesy of Master Lei Yixin)

The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial

(Image courtesy of Master Lei Yixin) It was 1963, and 14-year-old Ed Jackson Jr., ’73 FAA, wanted to be part of history as civil rights leaders flocked to the District of Columbia.

“When I was young in McComb, [Miss.], and the March on Washington was taking place, I really wanted to be present,” Jackson says. “But my mother was fearful to travel across the South in those days. I couldn’t understand it, but she did.”

She told her son his time would come.

“She said, ‘You’ll have the opportunity to make your mark,’” Jackson says and pauses with a smile.

“Mama was right.”

Nearly 50 years later, the architect’s mark is on display in our nation’s capital for the world to see. Nestled amid the cherry blossom trees on the northwest bank of the Tidal Basin stands the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial, honoring the man – and martyr – who served as the engine of the U.S. civil rights movement. Jackson, executive architect, has been a shepherd and a steward of the project for more than a decade.

“People want me to express my emotions” now that the memorial is complete, says Jackson, a retired Army major. “But in the military, if you become emotional, you lose your competitive edge.

“I look at it as though it’s a mission. … I have, for the last 15 years, looked at it that way.

“I’m sure the time will come when I will step back and have a moment to exhale like a lot of people do when they come here.”

That’s exactly what visitors do. The memorial, dedicated on Oct. 16, has been open to the public since August and draws steady crowds. School tours mingle with groups of World War II veterans as people pose for pictures and admire the view.

Jackson makes clear that this is not a monument – a fixture that marks an event in the past – but a “living memorial” to Dr. King and his ideas.

The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial, the only one on the National Mall not dedicated to a president, includes massive stonework; flowing water; a 450-foot, curved wall bearing King’s words; and nearby cherry blossom trees whose April flowering will coincide with the month of his assassination.

(Image courtesy of Master Lei Yixin)

FROM THE MILITARY TO THE MEMORIAL

During his undergraduate years at the University of Illinois, Jackson was a member of the Reserve Officer Training Corps, and it was through his ongoing military service that he became connected to the memorial.

Stationed in South Korea in 1995, where he was assigned to design military hospitals, Jackson drew the attention of a colonel who asked him if he had ever pledged a fraternity.

“‘I see [you’re the type who] can make a difference,’” Jackson recalls the colonel saying. “‘In order to make a large contribution, you need to be part of a larger organization.’”

The wheels were put in motion in 1996, and Jackson, then in his 40s with a doctoral degree in architecture, found himself in a situation similar to that of a college freshman – hoping for entry into Alpha Phi Alpha, a prestigious African-American fraternity whose long list of prominent members includes former Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall and King himself.

Barely six months after selecting Jackson, the fraternity approached him about taking on a special project. For years, the organization had been working to create a memorial to King, a goal first discussed in 1983 by five fraternity brothers casually sitting around a table. The group expected construction to take two years and cost approximately $2 million, Jackson says. In the end, the completed memorial cost $120 million, with Jackson devoting nearly 15 years to managing the project from initial design to final completion. “Their passion was infectious, and I got swept up in it,” he says.

NOT WITHOUT CONTROVERSY

The tribute to King aligns with the Lincoln Memorial (designed by UI alumnus Henry Bacon, Class of 1885) and the Jefferson Memorial. Forming the core of the design is a line from King’s iconic “I Have a Dream” speech: “With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope.”

Two large stones representing that mountain form an entrance to the memorial, while the “stone of hope,” from which King appears to be emerging, pushes forward into the plaza. Engraved on a surrounding wall, 14 quotations from the eloquent leader speak of justice, democracy, peace and love.

Despite the long-awaited opening of the memorial, King’s likeness has drawn controversy, just as King himself did in guiding the civil rights movement of the last century. Some say the face of the civil rights icon looks too confrontational. Jackson shakes his head at that, as though he can nod away the fuss.

To decide upon the visage, sculptor Lei Yixin offered four possibilities, from which King’s children indicated the one that most resembled their father. When daughter Bernice saw the final product and said, “That’s Daddy,” Jackson says it was “the only confirmation I needed.” For his part, Jackson thinks King looks “professorial,” with a scroll clutched in one hand.

The choice of Yixin, who is Chinese, as the sculptor of record also raised eyebrows. It’s clear that this frustrates Jackson, who had searched diligently to find the best artist to portray the minister, a recipient of the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize.

“The people who make these comments obviously have not embraced what Dr. King was all about – an inclusive society,” Jackson says.

During the lengthy process of finding an artist, the design team had stumbled across a stone carvers’ symposium in St. Paul, Minn. It was there, among the world-renowned sculptors assembled, that the team found Yixin.

“All the other sculptors said, ‘Yes, I’d like to do this.’ He said, ‘Yes, I can do that,’ and that struck a chord,” Jackson says. “He pulled Dr. King out of stone.”

Executive architect Ed Jackson Jr. has spent more than a decade managing the King memorial project from the glimmerings of an idea to its final completion. (Image courtesy of Ed Jackson Jr.)

INSPIRED BY THE QUAD

Born in Aurora, Jackson and his family settled in Mississippi when he was 9 months old. Returning to Illinois for college was an adjustment.

“I didn’t even own a coat that would keep me warm,” Jackson says. He also had to adjust to cultural differences. While only a small number of minority students were on campus, Jackson says the U of I “went out of its way to open doors” for them.

“It was difficult to have an immediate rapport with people,” he recalls, so a fellow African-American student asked the University for a house where minority students could work and gather. “It was not a fraternity but a social setting,” Jackson says. “That was necessary for us to succeed in that environment.”

Those were years of upheaval across the nation. As the Vietnam War was winding down and the Watergate scandal was coming to a head, Jackson concentrated on his education. “I was so concerned about being successful in architecture that I never attended an Illinois football game,” he says. But it wasn’t all work. Jackson spent a lot of time on the Quad.

“It is such a magical space,” Jackson says. His architect’s eye sees a well-executed spot that is full of life, even in the dead of winter.

When a UI class required him to enter a national design competition, Jackson’s favorite space served as inspiration. Charged with the task of designing a city plaza that would entice people to gather, Jackson thought of the Quad and the community it created through common space. He finished second, with the top spot going to a professional architect.

“One thing I looked for on every campus after was the magic that was created on the Quad,” Jackson says. And the elements that evoke that allure – a combination of openness and intimacy offering places to sit and vistas to see – are also incorporated in King’s memorial.

“If we created a space to give magic to the experience,” Jackson says of the design’s intent, “people would want to come and spend time and read the quotes on the wall.”

HOW FAR AMERICA HAS COME

While Jackson has been a key figure behind the memorial, he is quick to deflect praise to his team – and it’s obvious that it is his team. He talks about the roles of everyone from the sculptor to stonemasons, many of whom he knows by first name. Jackson’s ardor and attention to detail influenced all of the workers.

“The passion they brought to the task is reflected in the product,” Jackson says of his group. “I’m obviously proud of what we’ve been able to accomplish.”

At the end of the day, Jackson was most concerned about making his fraternity brothers and King’s family proud. He believes he has kept his vow to King’s widow, the late Coretta Scott King, that the memorial would “befit the sacrifice she, her husband and her family made on behalf of this country” and would “encourage others to take up [King’s] message.”

Having fulfilled those promises, Jackson now looks to the public to judge his work. Generally unrecognized by the crowds, “I stand among them and listen to the comments,” he says. “My satisfaction is drawn from their satisfaction. They are in awe of the likeness and the quality of the environs. … They’re the ones I really try to reach out to [now in order to] produce something that moves them in a profound way.

“[The memorial is] representative of how far America has come,” Jackson says. “I think a lot of that is reflected upon when people come and look at this piece.”

Master is a freelance writer and editor in Washington, D.C.