Ready and Able

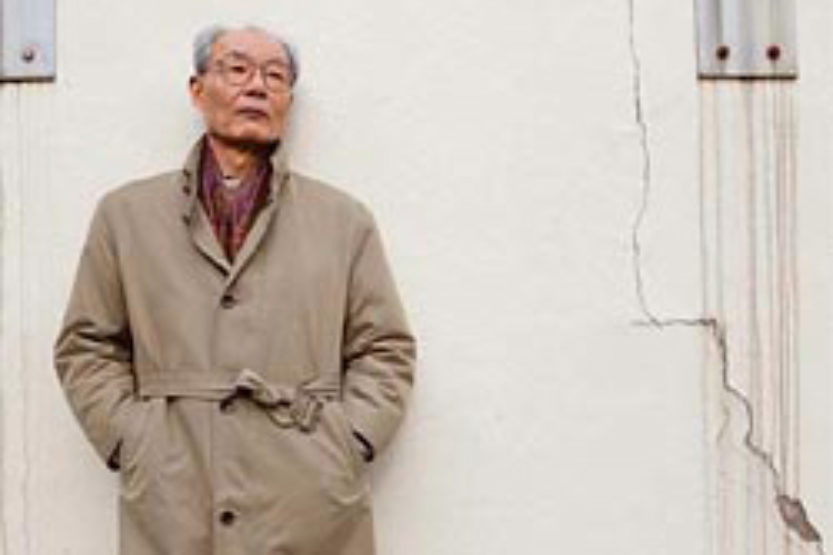

Nobuhiro Shiotani, of the Skilled Veterans Corps, which he co-founded. The group is offering its help in coping with the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant disaster.

Nobuhiro Shiotani, of the Skilled Veterans Corps, which he co-founded. The group is offering its help in coping with the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant disaster. Outfitted in a bulky hazmat suit and oxygen mask, his movements restricted, his vision clouded by the fog of his own breath, Nobuhiro Shiotani, MS ’66 ENG, was in a place few people could ever want to be – the poisoned realm of destruction that is Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant.

“I couldn’t move freely, couldn’t move my arms or look around. Even to screw or unscrew a bolt, even that sort of simple job, would be quite difficult under such circumstances,” the gray-haired physicist recalls of his trip last July into the ruptured facility, which was leaking radioactive cesium and other poisons into the water, soil and air. “A full face mask narrowed visibility, and breathing through charcoal filters was tough, voice communication was very limited; it was hot in

sealed overalls.”

Such were the extremes caused by far greater extremes of a few months earlier – March 11, 2011, to be exact, when an earthquake so mammoth that it shifted Earth on its axis struck northeast Japan, setting off a tsunami that deluged the coastline within 30 minutes. In one of the worst natural cataclysms in the island nation’s history, thousands of residents were drowned or swept out to sea by the wall of water. It also took out infrastructure, decimating whole towns, damaging roads and railways and leaving millions without electricity or water.

At the Fukushima Daiichi plant, a 1970s-era nuclear facility that sits on a stretch of scenic coastline 150 miles northeast of Tokyo, the tsunami knocked out the cooling system and set off the most devastating nuclear disaster since the 1986 explosion that destroyed the Chernobyl plant in Ukraine. As three of the Japanese facility’s four reactors began to melt down, some 80,000 nearby residents were evacuated, leaving behind a deserted landscape, incipient explosions of hydrogen gas and the ongoing release of radioactivity into the water and atmosphere.

For Japan, a nation that had staked its future on the safety of nuclear power, the catastrophe could mean only one thing: Rome was burning.

Critics lambasted a misguided energy policy reliant on a technology that could recoil and bite like a snake. People worried the food chain was poisoned. Fearful residents as far away as Tokyo began wearing protective masks, no longer trusting the air they breathed. Yet a few months later, Shiotani, a retired solid-state physicist, volunteered, along with four colleagues, to venture into Fukushima Daiichi’s deadly, pulsing heart.

He wasn’t even afraid. Instead, the 73-year-old widower, who had spent his formative years studying at the University of Illinois, felt a stabbing sense of guilt.

KEEPING ALIVE AS A RESEARCHER

Shiotani looks like a scientist. He’s a small-framed man with oversized glasses and a deliberate demeanor, who likes to keep his sleeves rolled up, as if ready to launch some new experiment. He keeps a box of smokes in his right breast shirt pocket, a half-pack-a-day guy always ready for a contemplative cigarette break.

This modest demeanor conceals a boldness that goes back decades. In the 1960s, after graduating from the University of Tokyo, Shiotani took a job at a government-supported institute that was too underfunded to finance any first-rate research. Then, upon reading the Physical Review, a prestigious physics journal, he was “thunderstruck” by a paper on nuclear magnetic resonance written by T.J. Rowland, a physical metallurgy professor at the University of Illinois.

The upshot, as the two retired scientists saw it, was that at their age they would likely as not succumb to some other malady long before a radiation-prompted cancer could kill them. So why, they reasoned, should the nuclear plant’s operator subject the young to such perilous doses of radiation?

On an impulse, Shiotani dashed off a letter, seeking a spot on Rowland’s research staff. To Shiotani’s amazement, Rowland agreed and even helped provide funding. “Looking back, it was the start of my career as a physicist,” Shiotani says. “The campus had a cosmopolitan atmosphere, and I learned lots, including my English, which helped me later in many ways to keep myself alive as a researcher.”

It also was the beginning of a lifelong friendship between the mentor and protégé. Shiotani arrived on campus in 1964 and received a master’s degree a year and a half later. After that, he worked full time as Rowland’s research assistant.

At night, after dinner, the professor would often visit the lab where Shiotani was working, an area Rowland recalls being decorated by the origami birds and figures created by his student. Shiotani says of Rowland, “He taught me a lot of things during those evenings. Not just about physics but about life.”

Over the years, the two scientists have kept in touch, mostly by email, but whenever Shiotani attends a conference in the U.S., he visits his old teacher. Now a UI professor emeritus, the 84-year-old Rowland applauds the work his former student has undertaken in connection with the Fukushima Daiichi disaster. “I told him that it was a tremendous thing he’s doing,” Rowland recounted to the Los Angeles Times, adding that the project shows that “anybody who can prove they’re still a competent scientist can help if you ask them.”

The crippled Tokyo Electric Power Co. (TEPCO) Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power station is seen through a bus window in Okuma Town, Fukushima Prefecture, Japan, on Nov. 12. Three of four reactors at the facility, which is located approximately 150 miles from Tokyo, went into meltdown on March 11, 2011, after a tsunami knocked out the cooling system.

SHIELDING THE YOUNG FROM A TERRIBLE LEGACY

Not long after the catastrophe struck, Shiotani and his friend, Yasuteru Yamada, met at a favorite Tokyo coffee shop. There, the retired scientists hatched a plan.

Nearly one-third of Japan’s population is over age 60, and the two feared that the old could be leaving behind a terrible legacy. “This nuclear reactor was the brainchild of our generation,” Shiotani told the LA Times. “And we feel it’s our job to clean up the mess.”

Their generation, he and Yamada knew, had benefited from nuclear power – using it to heat and light their homes and offices. It had even warmed the bottles they fed their infants. Japanese experts had been vocal proponents of the very same technology which had now seemingly betrayed them. While neither Shiotani nor Yamada, a retired plant engineer, had ever worked in a nuclear plant, they and many other scientists their age had lent their know-how, support and energies to the creation of such facilities.

The two men understood that the younger and often unskilled workers being sent to clean up Fukushima Daiichi could well become nuclear-lab rats, exposed to dangerous amounts of radiation and unaware of the long-term risks. The pair also knew that cells reproduce more slowly in the bodies of the old and that any radioactive-induced cancer resulting from cleanup-related exposure would take much longer to develop in them than in younger people.

The upshot, as Shiotani and Yamada saw it, was that at their age they would likely as not succumb to some other malady long before a radiation-prompted cancer could kill them. So why, they reasoned, should the plant’s operator, Tokyo Electric Power Co. (TEPCO), subject the young to such perilous doses of radiation? Old-timers could do the job just as well, with far fewer residual effects.

Thus the pair decided on their goal: Enlist a battalion of fellow retired scientists and researchers to venture inside the nuclear plant and use their decades of expertise to help stabilize the still-smoldering reactors. In the months following the disaster, Shiotani and Yamada made phone calls and sent letters and emails to colleagues present, past and long-lost. Eventually, they assembled a crew of more than 600 volunteers, including former electrical engineers, forklift operators, high altitude and heavy construction workers and even retired members of the military special forces. Also on board are engineers who had belonged to the original design and construction team for Fukushima Daiichi, as well as technicians who had provided maintenance for the plant.

The youngest was 60, the eldest 78.

Shiotani and Yamada have named the group the Skilled Veterans Corps, formed to help mop up after a conflagration and protect the health of younger generations.

While the press has played up what it perceives as the particularly Japanese quality of quiet sacrifice on the group’s behalf, Shiotani calls this nonsense. “Remember 9/11?” he asks. “People in New York made a personal sacrifice to gather around Ground Zero to help [those] unfortunately involved in the disaster. Is that part of ‘American culture’? If so, then Japanese culture is no different.”

Without a wife or children, Shiotani didn’t have to ask permission to embark on his mission. Even so, he’s tired of the issue and sometimes feels as if he and his fellow retirees are regarded as little more than naive children. “The subject of ‘What did your wife say? What did your kids say?’ rarely comes up at the SVC,” he says. “Everybody [in the group] respects everyone else’s decision to join.”

“Remember 9/11? People in New York made a personal sacrifice to gather around Ground Zero to help [those] unfortunately involved in the disaster. Is that part of ‘American culture’? If so, then Japanese culture is no different.”

Yet Shiotani’s involvement surely shows how emotional strength can overpower physical vulnerability and personal loss. A decade ago, he lost his wife to intestinal cancer. Soon after her death, Shiotani learned he was stricken with the same disease. The widower was lucky; doctors caught his malignancy early. But the weight of such an illness does not go away easily. These days, Shiotani sees the young workers who have been hired to clean up Fukushima Daiichi’s nuclear spillage and imagines them, decades later, facing cancer as well.

The thought sickens him.

‘THE FIRST DOT OF LIGHT’

From the beginning, Skilled Veterans Corps members have faced a major obstacle: convincing both the government and power company to take them seriously. Last summer, group members approached TEPCO to show that they brought a serious scientific solution to the problem, not merely the musings of a bunch of loony old people.

Yasuteru Yamada and Nobuhiro Shiotani, second and third from left above, co-founded the Skilled Veterans Corps to help with remediation work at Japan’s crippled nuclear power plant. They were at a meeting of the group held in Tokyo in January.

In the initial meeting, TEPCO officials worried about the SVC’s legal status and then fretted about insurance coverage. But Shiotani and the others would not go away. The organization registered as a nonprofit corporation and is trying to upgrade its status to become a public one. The SVC also devised a plan to cover members with accident compensation insurance and health care.

Finally, TEPCO officials made an offer. They would take the scientists on a tour of a reactor. For Shiotani, the move was a start.

On July 12, Shiotani and four other SVC delegates donned protective gear and were escorted into the No. 4 reactor, which had been under inspection at the time of the quake and did not suffer any meltdown. The group spent approximately 20 minutes there, recalls Shiotani, who had never before been inside a nuclear power plant.

“It was dark. Streaks of light came in through holes in the damaged ceiling,” he says, describing how he eased up a narrow staircase to the building’s top floor. Soon, a meter that measures radiation exposure began ringing, signaling the group to leave the area. Perhaps cavalierly, Shiotani didn’t worry about the danger. “A certain amount of radiation does not pose any risk,” he says. “However, it was hot in there, and what I feared was heat stroke, not radiation doses.”

During the tour, Shiotani watched the unskilled contract workers, young and middle-aged alike, come and go – perhaps unaware of the extent of the dangers they faced each day. These were precisely the people that Shiotani and the SVC were trying to protect.

Afterward, SVC members began to suspect that TEPCO was merely paying lip service to their idea, so in August, the group made what Shiotani calls a “strategic retreat.” While they have not abandoned the idea of working within the Fukushima Daiichi plant, the volunteers have switched their energies to convincing the government to accept their help on another project: community radiation monitoring.

SVC members now hope to help plot radiation levels in communities within a 12-mile radius of the ailing nuclear plant – communities the Japanese government has evacuated because of the continued threat of radiation poisoning. While TEPCO engineers have been conducting the monthly monitoring program, gauging radiation levels at 50 designated sites, Shiotani believes there’s a shortage of qualified data collectors. Having persuaded officials to allow members to attend training sessions, SVC now has a radiation monitoring team. It’s headed by Shiotani.

He calls the development “the first dot of light we [can] see in complete darkness” since organizing the effort. But he remains cautious. “I have [personally] been contemplating reasons why the SVC’s offer of help has been neither accepted nor rejected by our government and TEPCO,” Shiotani says.

“The tsunami washed away man-made structures like moles, breakwaters, banks, houses, buildings, bridges, railroad beds … leaving the crippled reactors and devastated lands behind.

“But the tsunami did not wash away the Japanese nuclear energy Mafia, ‘Gennshi-ryoku-mura,’ which consists of politicians, bureaucrats, technocrats, scientists and engineers who earn their daily bread from the Japanese electric power industry,” Shiotani says. “They are closely united to protect their interests. They don’t want the SVC, a total outsider, to touch their dead babies – [which], although dead, [are] still potentially hazardous and dangerous.

“I am becoming less optimistic about the SVC’s future,” he says, “but at the same time, I believe now is not a time to give it up.”

Shiotani will continue to be driven by the dual forces of his understanding of technology and his acute – even painful – personal sense of the ethics demanded by the nuclear cataclysm in his country. The scientist recalls, as he has recalled many times before, his reaction to the news of March 11, 2011.

“This is the greatest disaster this nation has ever experienced,” he recalls thinking. “All the nuclear reactors aren’t safe. This accident is going to cause great damage to people in Japan.”

Not if Nobuhiro Shiotani can help it.

As Seoul bureau chief for the Los Angeles Times, Glionna has covered the aftermath of the March 11, 2011, earthquake and tsunami disaster in Japan.