Lady in Waiting

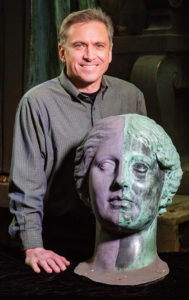

Alma Mater's head offers a vivid before-and-after study in laser cleaning performed at Conservation of Sculpture and Objects Studio in Forest Park, Ill. (Image by L. Brian Stauffer)

Alma Mater's head offers a vivid before-and-after study in laser cleaning performed at Conservation of Sculpture and Objects Studio in Forest Park, Ill. (Image by L. Brian Stauffer) Early on the morning of Aug. 7, 2012, after many long seasons of corrosive Midwestern weather and a short summer of delay, an hour like no other came to the University of Illinois. Alma Mater was leaving campus. Personnel and equipment worthy of a major construction project massed at the corner of Green and Wright streets in Champaign. Amid a buzz of workers, supervisors, spokespeople and onlookers, the sculpture group—which also includes the figures of Learning and Labor and a klismos (throne)—was cordoned off with yellow police tape, strapped to a red hook on a white crane and swung into the air.

An Illinois alumnus, sculptor Lorado Taft said he created “Mother” to be visited and even climbed on by students. (Image courtesy of UI Archives)

“Alma,” as Illini affectionately know her, was bound for laser cleaning at the Conservation of Sculpture and Objects Studio (CSOS) in Forest Park, Ill. It’s a spa, of sorts, for beautiful but aging statuary such as herself. Classical sculptor Lorado Taft, 1879 LAS, MA 1880 LAS, HON ’29, had fashioned his campus Mother figure, as he wrote in a letter to a friend, to be sturdy enough that students (who would dub her the “Ideal Chaperone”) “may keep the bronze throne polished by their visits.” Still, bronze is perishable. Moving around enormous bronze objects is downright worrisome.

Andrzej Dajnowski, who is director of CSOS, watched as the crane lowered Alma onto a set of heavy-duty sawhorses. The conservator picked up a flashlight and maneuvered himself beneath the 5-ton sculpture, gazing up into bronze hollows inert with air more than three-quarters of a century old. Staring back at him was a new and unpleasant revelation. The iron bolts holding together Taft’s magnificent creation were disintegrating. Some had vanished entirely. The restoration had just grown exponentially more complicated.

“I had to rethink,” Dajnowski recalls. He extricated himself from beneath the massive figures. Soon the crane would hoist the sculpture group up again and onto the flatbed of a tractor-trailer, to be padded and shrink-wrapped and strapped down for the trip to Forest Park. Dajnowski shared the news with Jennifer Hain Teper ’06, chairwoman of the committee that spearheaded the drive for the restoration. Outfitted in hardhat and cheerful at the day’s progress, she responded with a question, rhetorically framed.

Alma would still be back for Commencement 2013.

Right?

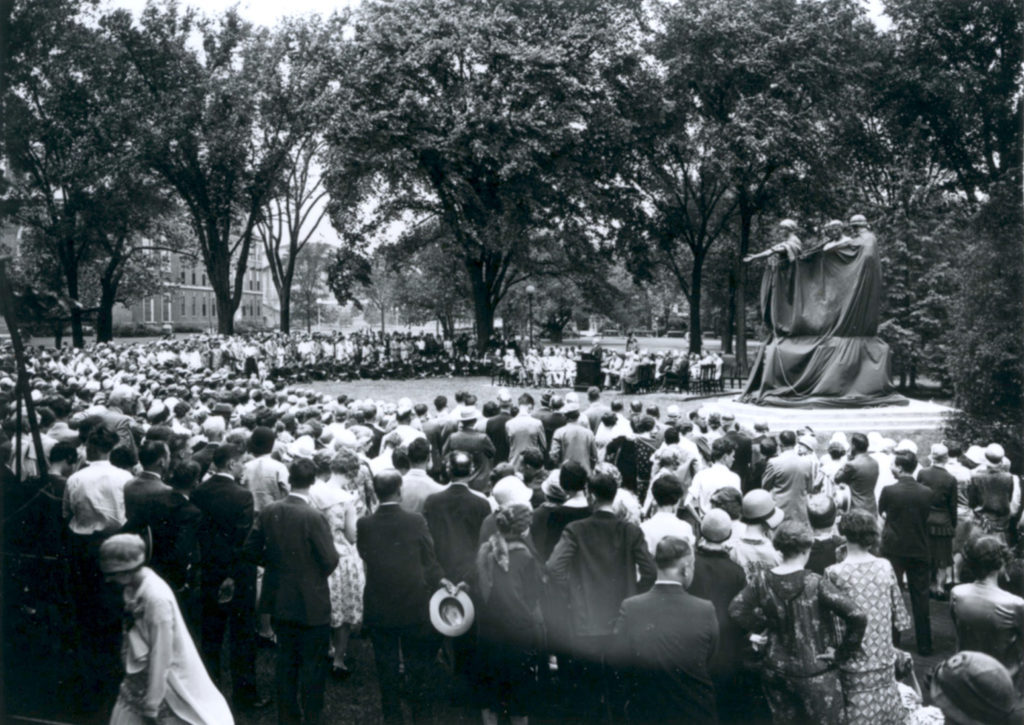

The sculpture group, consisting of three figures and a throne, is dedicated on June 11, 1929. (Image courtesy of UI Alumni Association)

Taft’s Mother, and how she grew

The classes of 1923-29 presented Alma Mater to the University on June 11, 1929, a gift also supported by the UI Alumni Fund and Taft himself, a prolific master of classical sculpture, whose work ranges from the 50-foot-tall Black Hawk Statue near Oregon, Ill., to the Columbus Fountain at Union Station in Washington, D.C.

Taft’s signature on Alma is as modest as the lovely dedication inscribed on her granite base is far-reaching: To thy happy children of the future those of the past send greetings. Hundreds of thousands of those children of the future have since wandered Alma’s campus and walked her halls and gone on to individual futures shaped in ways major and minor by their days at Illinois. The intervening decades have also bestowed a special celebrity on the 13-foot figure, especially after she was moved from her original location outside Foellinger Auditorium to a far more visible and welcoming site near Altgeld Hall and the Illini Union.

She has photo-posed with untold numbers of beaming young people clad in caps and gowns. She has also appeared in her own ultra-X-large cap and gown, as well as in basketball jersey, in enormous orange T-shirt, and in headband and runner’s bib for the Illinois Marathon. She has wielded an electric guitar for the Ellnora guitar festival and popcorn for the Roger Ebert Film Festival. Her image has lent gravitas and elegance to University publications and websites. A virtual Alma has even mastered social media, tweeting and posting campus phenomena and alumni achievements.

The decades, though, also washed Alma green, the powdery, slightly luminous, algae-reminiscent haze that is copper and chloride corrosion. The look was not unbecoming to a being as handsome and timeless as herself, and many Illini had simply come to think of Alma as green. But deterioration streaked her cheeks like teardrops.

“It’s important to note,” says Jim Lev ’73 FAA, MARCH ’74, an architect in capital programs for the Urbana campus, “that green patina is not a good thing.”

Removal of Alma Mater statue for restoration, August 7, 2012. Rigger Ben Bergeven-Smith (left) and senior rigger Luke Boehnke secure the Alma Mater statue for removal. Video of the removal shown here.

Of chemistry and X-rays

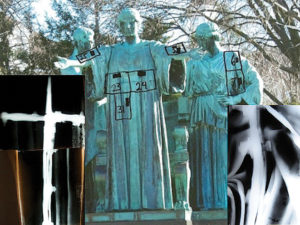

X-rays show major deterioration of bolts holding sculpture together. (Image courtesy of Andrzej Dajnowski)

By 2009—80 years after the sculpture’s dedication—the Preservation Working Group, a committee charged with watching out for the best interests of objects of all kinds at the University, was taking a very hard look at Alma Mater. “We realized that the sculpture was in worse shape than we thought,” according to PWG’s Hain Teper, who heads preservation and conservation for the University Library. Three years of study and support-seeking ensued. Chancellor Phyllis M. Wise granted $99,962 (in nonpublic, non-tuition funds) for removal and cleaning of the sculpture. Bids went out, and CSOS was awarded the job, expected to take a few months. Alma, the committee promised, would be back for Commencement 2013.

But after Dajnowski got the sculpture back to his studio in Forest Park, chemical analysis and X-rays confirmed her condition to be extremely serious and fragile. When Taft created the Alma Mater group, he used approximately 1,000 iron bolts to hold the figures and klismos together. Alas, iron and bronze are not friendly on an elemental basis. Combined, they create galvanic cells, causing the iron to rust. And the lead and tar caulking on the sculpture’s 50 pieces had deteriorated in places, resulting in water erosion of the bronze.

Laser cleaning—or, more precisely, laser ablation—began soon after Alma’s arrival in Forest Park. But University approval to address the further problems took time. With alumni and the press extremely interested in Mother’s condition, a kind of lockdown at the studio ensued. “It happened quite often that somebody just rang the doorbell and expected to see the sculpture,” Dajnowski says. Other projects crowded the docket—as conservators and plastic surgeons well know, the world is full of aging beauty. When the go-ahead came, Dajnowski and his staff were facing a restoration twice as long, three times as expensive and infinitely more difficult than originally anticipated.

Partly disassembled and green with corrosion, Alma Mater awaits restoration alongside her throne and companion figure of Learning. (Image by L. Brian Stauffer)

Corroded iron bolts holding the sculpture group together are replaced with bolts of silicon bronze. (Image by L. Brian Stauffer)

To replace the deteriorating bolts, the heads had to be removed from the sculptures. Alma’s left arm was also separated from the main figure. (The arm alone weighs 400 pounds.) Labor had to be taken apart, while access to the interior of Learning was “very tight,” Dajnowski says. “We could not work very fast in removing all of those bolts and

replacing them.”

New bolts of silicon bronze were fabricated, as well as negative casts of bronze to fill gaps between the sculpture’s leaded joins.

On March 4, 2013, the University released the revised estimate for restoration: no more than $360,000.

And announced that—for the first time in 83 years—Alma would not be with her children at graduation.

In the hall of the conservator

The Conservation of Sculpture and Objects Studio is housed in an Aldi-sized space—13,000 square feet, including offices and a dining/conference room with a long, stately table, massive chairs and the homey aroma of savory breaks taken there by staff. Flanked by twin loading bays, the main workshop is illuminated by a big skylight and warmed with gas heaters. The place is a lively, authoritative jumble of equipment, materials and statuary. A bronze Native American maiden stands with a bull (the sculpture was salvaged from the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair). A colorful St. Patrick looks fresh from some Irish congregation. Brass lions growl, and a brass elephant raises its trunk. A huge clock sits quiet, bereft of clock tower. A massive urn awaits the flowers of summer.

Even so (and despite the absence of their heads), Alma and Learning tower over the studio, as they have towered over its agenda since Aug. 7, 2012. Poised on curvy, dog-toed legs, the klismos seems alive, ready to click away on pointed claws. Labor lounges off to one side, recumbent in three pieces. Looking into his torso is like a glimpse into the brachiating geology of a cave, albeit a cave glittering with bright new bolts.

The Forest Park studio of conservator Andrzej Dajnowski is lively with restoration projects. Note heads of Labor and Learning and Alma Mater’s arm in the foreground. (Image by L. Brian Stauffer)

Bartosz Dajnowski, Andrzej’s son, dons eyewear with protective green lenses and a gas mask, then begins gently to stroke Alma’s robe with the laser. (While the laser beam itself is invisible, its action reflects off the metal like a sideways darning needle of light.) Behind him hums one of the studio’s two custom-built German laser machines, each powered by a huge electromagnet.

“Don’t put your wallet near the transformer supplying electricity to the lasers if you have credit cards,” Bartosz warns. “Don’t step on the hose coming out of the machine, because it contains fiber optic cable. And whatever you do, don’t look at the beam without protective eyewear.” Each laser pulse lasts only 100 nanoseconds, and the beam can injure the retina exponentially faster than the eyelid can drop.

Bartosz—who holds a master’s degree in conservation from Winterthur/University of Delaware and has traveled the world doing laser research and giving presentations at conferences—moves the instrument down Alma’s robe. Green haze abdicates to bronze metal, corrosion vaporizing into an exhaust extraction tube overhead. The laser is calibrated to remove the surface corrosion and leave the bronze beneath intact. In the ablation process, corrosion molecules on the surface of the sculpture absorb laser energy and are vaporized. The process also creates a plasma on the bronze surface, which reacts with oxygen in the air and forms a very thin, fresh patina of copper oxide. Application of more chemical patina and a protective wax coating are the last steps in the restoration before Alma Mater returns to her plinth among the hemlocks and crabapple trees outside Altgeld Hall.

Topping out at Philadelphia City Hall

A native of Poland, Dajnowski studied art conservation from the time he was a young man, eventually earning a doctorate from Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun, where he wrote his dissertation on the influence of the laser beam on copper alloys and practical application of the ablation process in fine art conservation. Since moving to the U.S. in 1985, he has burnished a reputation as the man to see if you’ve got a sculpture in trouble.

“Andrzej is very informed and at the forefront of people doing this kind of conservation,” notes University architect Lev. “He travels all over the world doing this work.” Dajnowski’s projects have ranged from restoring the 1882 bronze sculpture of George Washington on Wall Street in New York, to removing graffiti from the ancient pictographs at Hueco Tanks in Texas, to laser ablation of the stone exterior of the Samuel M. Nickerson House in Chicago. Located on the Near North Side, the historic mansion was the first building in the U.S. to be laser cleaned.

Literally topping these achievements is the 2005-06 restoration of four massive bronze sculpture groups and four eagle figures on the Philadelphia City Hall clock tower. The sculptures—cast by Alexander M. Calder in the late 1800s—required replacement of more than 2,600 bolts, screws and other fasteners, as well as cleaning. The work, moreover, had to be restored in place, 400 feet above the street. A photo from the site shows the straight-down view from scaffolding to sidewalk, the latter far below but somehow looming. Laser cleaning and restoration on such a scale were heretofore unprecedented.

“It was kind of a curse,” Andrzej Dajnowski says of the Philadelphia project. “Because now I start looking at every sculpture as possibly having structural problems on the inside. Relating to the Alma Mater, I knew it was potentially possible. So that ‘curse’ from Philadelphia, in a way, saved us.”

A restored Alma Mater returns to her pedestal on April 9, 2014. (Image by L. Brian Stauffer/UI Public Affairs)

Triumphant, if tardy, return

Though Dajnowski maintains, with cool, professional resolve, that no sculpture he works on is dearer or more meaningful to him than any other, he does allow a special esteem for Lorado Taft. Taft worked on the Alma Mater in his Chicago studio and cast her at a Chicago foundry. The city is endowed with many of the sculptor’s works, and Dajnowski and his team have restored a number, notably the Fountain of Time, a massive, visionary work on the Midway, shaped from concrete and considered among Taft’s masterpieces. “Any artist, including Taft, would be happy because of what is going into this project. It is proving that the University is very serious about the Alma Mater,” Dajnowski says.

Perhaps echoing the ethos of Taft, the conservator adds: “You always want to give a perfect job at the end.

“And that perfection can drive you crazy.”

When Alma is reinstalled this spring, the moment will undoubtedly unleash dual rushes of joy to the campus and relief to the conservator. The lovely robed figure with calm face and outstretched arms is poised for a return to campus looking as beautiful as she has ever been, bronzed without and healthy within. Hail, Alma Mater. Your happy children of the past, present and future send greetings. And just in time for graduation, too.