Set master Anshuman Prasad

"I watched thousands of movies ... from really cheesy B-grade movies right down to big-budget ones like Armageddon, Deep Impact and Gladiator," Prasad says. "In those films, there was so much attention paid to sets and architecture." (Photo by Jeffrey Fiterman, renderings courtesy of Anshuman Prasad)

"I watched thousands of movies ... from really cheesy B-grade movies right down to big-budget ones like Armageddon, Deep Impact and Gladiator," Prasad says. "In those films, there was so much attention paid to sets and architecture." (Photo by Jeffrey Fiterman, renderings courtesy of Anshuman Prasad) Jamshedpur, India, is a major industrial center that boomed well before the rest of the Indian subcontinent hit its economic stride. Back in the 1980s, one of the signs your family was making it was that you got to watch videos. Even then, seeing a sort-of-recent Hollywood movie in the comfort of your own home involved a pretty serious commitment.

At least that’s how Anshuman Prasad, MARCH ’03, remembers it. The heavy lifting began at the video store, where a customer had to rent not just the videocassette, but the player as well—usually a clunky Panasonic unit that weighed you down all the way home. No wonder a simple viewing turned into an event. After the unit was hooked up to the Prasad family’s 20-inch TV, mattresses and other pieces of furniture were dragged into the living room until every square inch was taken, and even then there was never enough seating to accommodate the massive influx of friends and relatives who came to see the show.

It was from a perch in such a packed room that a 9-year-old Prasad, who is today one of Hollywood’s leading set designers, saw his very first movie: the 1978 version of Superman, starring Christopher Reeve and Marlon Brando. Prasad doesn’t remember being particularly taken by the plot or the acting; instead, the moment that affected him the most was distinctly architectural. “Superman is flying around Metropolis when he sees a cat burglar scaling a skyscraper,” Prasad recalls. “And then he lands, and he’s just standing sideways on the building’s glass façade, defying gravity and floating in the air. The effect was so real.”

Three decades later, Prasad creates similarly astonishing visual environments for global audiences numbering in the millions. If you have seen the cavernous Las Vegas hotel room where Bradley Cooper and Zach Galifinakis face all kinds of comedic craziness in The Hangover, or the austere Scandinavian torture chamber where Daniel Craig’s character comes close to death in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, you’ve seen his work. From the unconscious zaniness of contemporary suburbia in Little Fockers to the bleak future of Terminator: Salvation, Prasad has created the rooms our celluloid dreams inhabit.

Trained as an architect

Seven years after seeing Superman, Prasad was studying architectural design at the Manipal Institute of Technology, one of India’s foremost engineering schools. One of his teachers was Varkki George Pallathucheril, a visiting architecture professor from the University of Illinois. “He taught us architectural design,” Prasad recalls, “and it opened up my life to a whole other process of designing. It was a very good experience, and I kept in touch with him.”

At the same time he was immersing himself in his class work, Prasad often ducked into a local theater that showed films on videotape in order to pursue a parallel curriculum of his own devising. “I watched thousands of movies in this period,” he says, “from really cheesy B-grade movies right down to big-budget ones like Armageddon, Deep Impact and Gladiator. In those films, there was so much attention paid to sets and architecture compared to what Bollywood was producing in India at the time.”

After completing his degree in 1999, Prasad took a job at an architectural firm in New Delhi. The work was interesting; the firm designed office and home interiors, as well as large government projects. He worked on sustainable design—for example, designing an air-conditioning system without any electrical or moving parts. But Prasad found himself impatient with a profession that rewards even its most brilliant practitioners at a snail’s pace. “Frank Gehry is a big architect,” Prasad explains, “and when he draws something now—however convolutedly extravagant it is—people believe in him and he can get it built. But it takes many, many years for an architect to reach that level, if he reaches it at all.” A restless Prasad began thinking about Hollywood.

Armed with a recommendation from Pallathucheril, Prasad was accepted into the UI School of Architecture’s master’s program, enrolling in 2002. He knew exactly what he wanted to study—not Frank Lloyd Wright’s Robie House or Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe’s Seagram’s Building, but the architecture of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner.

To embark on an inquiry so novel, Prasad needed an ally and a mentor; his thesis advisor, Professor Kathryn Anthony, became both. “He did this very comprehensive review of movies from a variety of perspectives,” she recalls, “including the influence of physical environment on characters’ behavior and on the storytelling.” The finished product—“Beyond Mise En Scene: Narrative Through Architecture in Main Stream Cinema (1980–2002)”—stands out as one of the great adventure rides in the annals of UI graduate masters theses, packed with Hollywood action, horror and sci-fi, she says. Not one, but two, Bruce Willis futuristic sagas—12 Monkeys and The Fifth Element—receive star treatment. “His project was so good,” Anthony says. “It was one of a kind.”

During spring break at UI, Prasad visited Los Angeles, where as part of his research, he interviewed some of Hollywood’s leading art directors and production designers. “They were really friendly and helpful,” he says, “and more than happy to help me out.” Once Prasad completed his degree, some of the subjects he’d interviewed became his most valuable contacts. “I came from out of the blue and had no idea how to get started in the film industry—like who might be the right person to email. Through them, I was able to find out how the industry works, who hires you and what the expectations are.”

While watching the original 1978 Superman film on TV as a kid in India, little did Prasad know he’d one day end up designing sets for a much later installment of the Warner Bros. release, Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice. (Photo by Jeffrey Fiterman)

Live Free or Die Hard

In 2003, Prasad landed a job as an assistant in a special effects studio, whose owner helped him obtain a green card. He began working his way up, creating sets for a couple small-budget films. Within three years, he was hired as set designer for his first blockbuster—Live Free or Die Hard, which by happy coincidence starred Bruce Willis, one of the main protagonists of his UI thesis. One of his greatest challenges on that film was to conceive an elevator strong enough to accommodate an evildoer’s SUV as a passenger. “I remember being nervous before the screening,” Prasad says. “It was my first studio set design job, and I wasn’t quite sure how the thing would look on-screen. I had seen a few stills, so I knew what it looked like, but it was amazing to see it on-screen and all the action that went into it. On the whole, it was a learning experience; I saw how much ‘my’ set had come along. There was the lighting, painting and textures that brought it to life.”

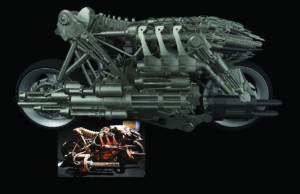

After that debut, it was onward and upward: Prasad has found continuous employment, working on the TV series Entourage and Big Love, and on films such as Rendition, Outlander, The Expendables, No Strings Attached, Ender’s Game and 300: Rise of an Empire. Each presented its own challenge. In Captain America: The Winter Soldier, Prasad was faced with the difficult task of designing an underground chamber that had, for five decades, housed the still-active brain of Arnim Zola, the hero’s not-entirely-deceased nemesis. “It was a tricky concept,” Prasad recalls. “The set had to look like the facility had been set up in the late 1960s, but it would have had the very latest and advanced technology of the era.” To capture the “retro futuristic” mood of that concept, the designer settled on a space inspired by an underground parking garage, with rows of thick columns. Then there were the aesthetics of the equipment that kept the evil mind alive and running. “The computers had to be somewhat sinister,” Prasad explains.

Immune to the elements

Prasad doesn’t regret spending his time designing buildings that aren’t real. “When I design a set,” he says, “I will often get to see that set just the way I originally visualized it.” Such real-world considerations, like the ups and downs of the real estate market or the need to include indoor plumbing or air-conditioning systems, never become a factor. “What we design, and how we go about it, allows us to be very, very free,” he adds. There is another hidden benefit, one even more extraordinary: Prasad’s buildings may be fictional, but they are immortal, immune to the elements and the passage of time. “You look at a building just five years old, and the rain and the sun will already have had an impact on it,” Prasad says. “But my set will never change. In real life, it might have turned to rubble, but on film, it will always be in the same pristine condition.”

Movies are a collaborative art form, and Prasad has plenty of company in his creative process. In the early stages of production, he constantly confers with an illustrator and production designer. Nearer to completion, he spends more time with studio construction crews. “The size of the art department varies, depending on the movie’s scale and scope,” Prasad explains. “For example, a science fiction film would employ a bigger crew as opposed to a drama.”

One of Prasad’s latest assignments has been for smaller screens, as the digital set designer for the Amazon original series The Man in the High Castle. Meanwhile, he has ambitions of becoming a movie production designer—hopefully sooner than later. To that end, he has been working with some friends on a Web series and on some ideas of his own. Lately, he also has been designing sets for Fox Television’s The Mindy Project, starring Mindy Kaling, the first Indian-American sitcom star. One episode was set in Kaling’s and Prasad’s mutual mother country and included outdoor scenes. Prasad designed a streetscape that drew on elements from his old neighborhood. “It would have been more authentic if we actually went to India,” he says, “but instead, we shot it on the Universal lot.”

Hasn’t gone Hollywood

Prasad is 40, but looks a decade younger, with a full head of dark hair, a close-cropped beard and inquisitive eyes behind narrow rectangular glasses. He favors what he calls “surfer-dude” attire—hoodies, jeans and baggy shorts. It’s not just a look—he actually is a late-blooming long boarder, embracing the larger Southern California lifestyle. While Prasad considers himself a part of the movie industry, he wouldn’t necessarily say he’s “gone Hollywood.” “I certainly feel a part of Hollywood, very welcome and rewarded for my talent,” he says. “Yet, I’d like to believe that I retain my unique cultural identity and even bring some of it into the melting pot that is Los Angeles.”

Sci-fi settings are a specialty for Prasad, whose fictional, futuristic designs come to life on the big screen. “When I design a set, I will often get to see that set just the way I originally visualized it,” he says. (Photo by Jeffrey Fiterman)

Despite the rigors of his schedule, Prasad visited UI School of Architecture several times the past year via video-conference. He’s been the featured guest in a seminar called Architecture, Cinema, Environment and Behavior, which is taught by Kathryn Anthony, his former thesis advisor. At the end of the first class, Anthony asked her students to raise their hands if they might consider a career in movie set design. Four arms shot up. “I believe one of the reasons they take the course is that they’re aware we have a UI alumnus who has done extremely well in the film industry,” she says.

Meanwhile, Prasad’s assignments continue to roll in, including one film on which he recently finished work. Prasad isn’t allowed to talk about the project, but we’re guessing it must have given him some special satisfaction. Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice doesn’t debut until March 2016, but Warner Bros. has already released a trailer of the film. For a few seconds, we get a glimpse of Henry Cavill’s Man of Steel plunging down the side of an office tower—defying gravity the way Christopher Reeve once did on a 20-inch TV screen in a living room in Jamshedpur, as a thrilled 9-year-old Anshuman Prasad looked on.