The early years

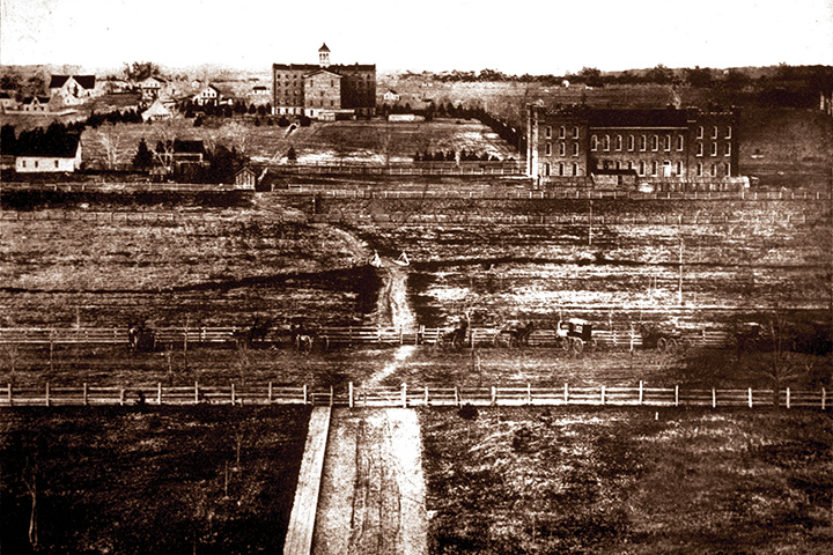

Animals of campus sometimes outnumbered students. (Photo courtesy of UI Archives)

Animals of campus sometimes outnumbered students. (Photo courtesy of UI Archives) Its beginnings were modest. When Illinois Industrial University opened its doors on March 2, 1868, the campus—if one could call it that—occupied a muddy pasture in the prairie town of Urbana. That day, the school’s three faculty members stepped forward to welcome an inaugural class of 50 men, all white, the majority from surrounding counties. By the conclusion of the first term, the University employed 10 faculty members and student enrollment totaled 77, more than half of them natives of Champaign County.

So lie the origins of the University of Illinois.

That first year, students paid a one-time matriculation fee of $10—a mere $172 when converted to 2015 currency values. Tuition was equally modest: $15 for Illinois residents and $20 for out-of-state students. Room and board were comparatively steeper in price, ranging from $112 to $130. Because rooms were unfurnished, students carted their own beds, desks and chairs to campus. Furnaces didn’t exist, prompting them to also cart small stoves to heat their rooms and to purchase coal from the University at cost.

Women soon enrolled, with Frances Potter Reynolds among the very first. Of her first day on campus in 1870, she wrote: “We arrived about midnight at our destination and the next morning took up our quarters in the University Building. You notice I say the building, for there was but one. A large, plain, red brick five-story building set down flat, in the black Illinois mud, with not a tree nor a shrub, a spear of grass nor a fence. It was as desolate a place as possible to imagine.”

Horticulture 101

In those early years, all campus activity centered on the University Building—nicknamed “The Elephant”—where students lived, learned, studied and worshipped. Students also were put to work sprucing up their surroundings, constructing boardwalks to circumvent mud, and later, landscaping the campus with trees, bushes and flowers. Students maintained a regimented schedule, cultivating grounds for two hours per day, five days a week. Their exertions weren’t without compensation: 8 to 12.5 cents an hour.

In 1874, the campus wasn’t much to look at. It was, however, growing. Enrollment had swelled to 400 students, representing the majority of Illinois counties, more than a dozen states, and the nations of Armenia, England, Germany, Greece and Japan. The school also enrolled nearly 100 women. Three new buildings had joined The Elephant: the Mechanic and Military Hall, the Farm House and University Hall (constructed where the Illini Union now stands).

Regimented living

University customs were true to their time, though today’s students would have chafed under some of the rules and restrictions that shaped the experiences of their fore bearers.

For nearly all of its first 25 years, the University banned the Greek system, with one administrator describing fraternities and sororities as “the traditional tinsel of a more barbarous time.” Consequently, they went underground, meeting in secret off-campus locations. In 1882, the University forced incoming students to sign an oath promising they would not join a secret society. However, it did an about-face in 1891, and the ban was lifted. In ensuing decades, the Greek system at Illinois emerged as one of the nation’s largest and most active.

Unlike the Greek system, the University harbored no reservations about religious worship. From 1868 until 1894, students were required to attend daily religious services in the campus chapel. During that period, Evangelical Protestantism dominated U.S. culture, coloring the fabric of its educational institutions. In keeping with other schools, the University’s first regent, John Milton Gregory, was an ordained minister.

The majority of students resented the requirement to attend chapel. By the late 1880s, their support for Gregory’s successor, Selim Peabody, had waned as a result of his strict policies, chapel attendance included. Beset by several student-initiated public pranks, including gluing his bible shut, Peabody realized he had lost support of the student body and resigned in 1891.

The requirement that male students participate in daily military drill exercises emerged as another bone of contention. Spurred by the Union Army’s lack of trained officers during the Civil War, the Morrill Act of 1862 required land-grant institutions such as Illinois to offer training in military science. The University’s first Board of Trustees took the provision a step further, mandating military training in an effort to establish Illinois as the “West Point of the West.” Each male student was, in effect, a cadet. The gray cadet uniform, modeled after those worn at West Point, was one of the highest costs of attendance at Illinois Industrial University.

Gradually, the University relaxed this requirement. By the 1870s, members of the military band—progenitors of the 20th-century’s Marching Illini—were excused from drilling. Seniors were exempted in 1881, and as a result of student protests, juniors were exempted in 1893. However, male freshmen and sophomores were required to serve in University battalions until 1963.

Debates, theatrics and more

When they weren’t engaged in classwork or mandated activities, students created a variety of outlets to channel their energies, including literary journals and newspapers (including The Student, which evolved into The Daily Illini); mandolin and glee clubs; stage plays; class contests, including tugs-of-war; and sports activities.

In the 1870s, student boardinghouses began creating baseball clubs. By 1879, the sport had grown so popular that the University established its own team. Likewise, football gained prominence, prompting Illinois to establish an official program in 1890. Students played on vacant lots, wearing street clothes and derby hats, tackling each other by the coattails. Faculty frequently participated in practice. Contrary to contemporary practices, tradition called for players to enjoy a heavy meal, including pie and ice cream, prior to games.

Despite their growing popularity, athletic events initially took a backseat to debates conducted by the Illinois Intercollegiate Oratorical Association and the activities of literary societies, including dramatic performances, social events, banquets and lectures. According to The Illini newspaper, baseball was “the activity of those left behind in the race for oratorical and literary honors.”

Students participated in a wide range of activities, including singing (Ladies Glee Club), riding motorbikes (Motorcycle Club) and playing tug-of-war. (Photo courtesy of UI Archives)

In his memoir of early student life at Illinois, On the Banks of the Boneyard, Charles Kiler recalled: “On the banks of the Boneyard …many an alumnus … got as much good from his membership in [the literary societies] as he got from class work in his particular field of study.” Kiler lamented that “the passing of these societies [in the 1910s and ’20s] was a distinct loss in student life.”

Students later spent time in contests among lower, mid and upper classmen, including Color Rush, Push Ball, Sack Rush, roller-skating matches and beard-growing competitions. They also engaged in interscholastic circuses, frequented campus bars and formal dances, and participated in “intramural sports” including panty raids, water fights, social protests and beer pong.

The takeaway: Each generation of Illinois administrators and students writes its own rules. That was as true of the early years as it is today.

Ryan A. Ross is the University of Illinois Alumni Association’s coordinator of History and Traditions Programs.