West Point of the West

1914 awards ceremony. (Image courtesy of UIAA Archives)

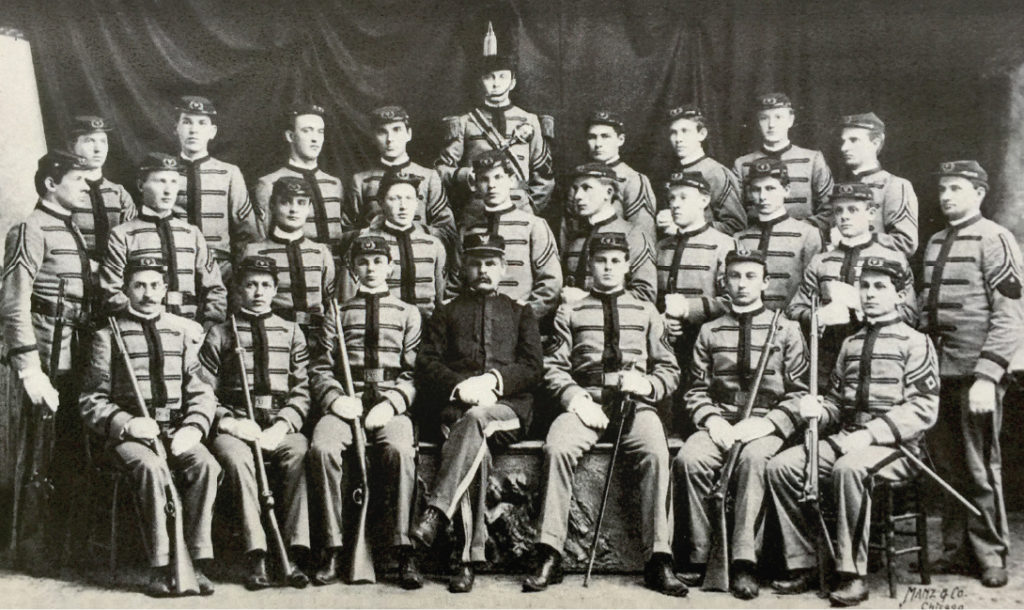

1914 awards ceremony. (Image courtesy of UIAA Archives) Outfitted in West Point-style dress grays and a blue scoop-shaped cap, Illinois freshman Clarence Shamel stood painfully at attention alongside dozens of other fledgling cadets. It wasn’t easy.

“We had our first drill today in the drill hall,” Shamel confided to his diary on Sept. 20, 1886. “We got along very well; it was very tiresome standing so erect.” A few weeks later, the freshmen cadets were issued their rifles, and Shamel’s inexperience with firearms was quickly evident. “In letting my gun slide down my side, the hammer caught in my coat pocket and tore a great hole in it,” he recounted on Nov. 3. It could have been worse: Later that semester, a running cadet stumbled and accidentally rammed his bayonet into another soldier’s shoe!

From its earliest years as the Illinois Industrial University, all male students were required to undergo military training. In May 1867, the school’s Board of Trustees made a momentous decision, declaring that the Morrill Act of 1862 called for compulsory military training at all land-grant colleges—and University authorities continued to endorse that interpretation of the Morrill Act for almost a century.

According to the University’s first catalog, the objective of the school’s military department was “to scatter through the state a body of men so far advanced in military art that, in case of war, they will furnish skillful officers ready to drill and lead the volunteer forces of the country.” The department was responding to a real need of the times: During the recent Civil War, the Union Army’s heavy losses were due in part to a shortage of trained officers.

The University’s founders ran the college like a military academy. John Milton Gregory, the school’s first regent, made no secret of his desire to turn Illinois into “the West Point of the West.”

“In the earliest years, male students marched in squads, worked in squads, responded to the call of a bugle rather than a bell, saluted the faculty, and were disciplined by adjutants in the dormitory,” wrote University historian Carl Stephens. “Until chapel was abolished in 1894, all students, men and women alike, lined up in companies in the corridors of University Hall before entering the assembly room for the daily fifteen-minute exercise.”

Under Professor Edward Snyder, the University’s military department flourished. A veteran of both the Austrian and Union armies, Snyder became commandant of Illinois’ military program during the 1869-70 academic year, formalizing its structure as the University Battalion and appointing student officers as drill sergeants and instructors.

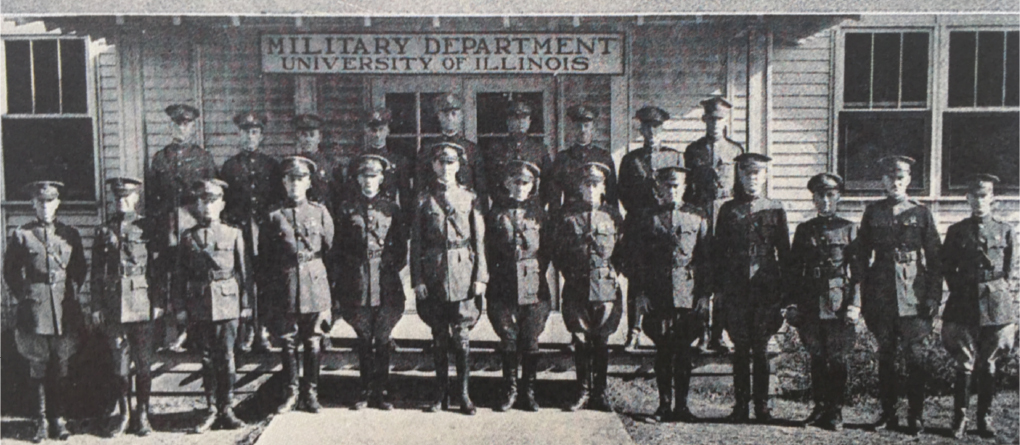

The 1925 University of Illinois Brigade. According to the University’s first catalog, the objective of the military program was “to scatter through the state a body of men so far advanced in military art that, in case of war, they will furnish officers ready to drill and lead the volunteer forces of the country.” (Image courtesy of UIAA Archives)

Dispatched to The Great Chicago Fire

The Battalion gave the struggling new college much-needed favorable publicity in October 1871 when 157 of its cadets were hurried onto a special midnight train to “the needy, terror-stricken, still-flaming Chicago” following the Great Fire. One company was dispatched to the city’s West Side to guard a supply depot while the rest of the Battalion patrolled the South Side. The State of Illinois awarded the cadets $3 each for their service to Chicago, a sum roughly equivalent to $62 today. The selfless students voted to use the money to “garnish with plaster” the walls of the newly constructed Mechanical Building and Drill Hall on Springfield Avenue. Ironically, the building burned down on June 9, 1900.

All students in the mandatory basic military course had to endure drill exercises an average of two to three hours a week on the Parade Ground—later known as Illinois Field—or on the second floor of the Mechanical Building in the Drill Hall, depending on the weather. The drudgery of drill eventually took its toll on student morale. One study found that between 1879 and 1884, six students were suspended for either disobedience at drill or missing it entirely. When a demerit system was established to punish such infractions, a whopping 87 percent of demerits were issued for violations related to order and attendance at chapel, military drill or military lecture. Writing in The Illini in 1879, an unnamed author poked fun at the University’s military training program, calling it, “a system devised by a wise and humane government … to give militia officers somebody to practice on.”

An 1880 training drill rebellion helped free University seniors from compulsory drill. “The final result of the rumpus was glorious,” student historians of the Class of 1881 crowed. Another such “rumpus” in 1891 ended mandatory military training for Illini juniors as well.

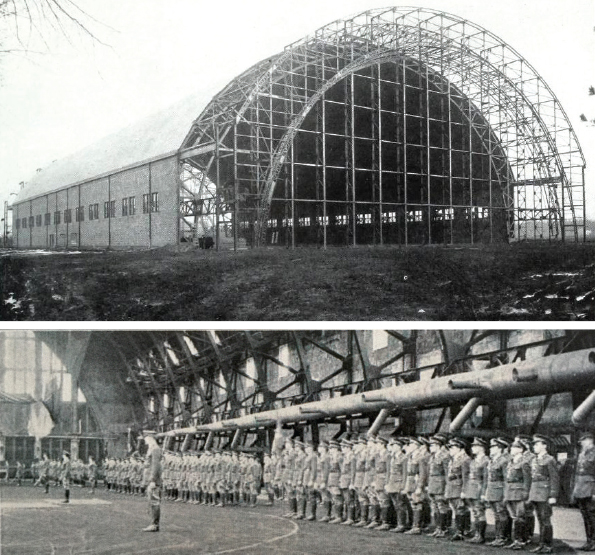

1915 construction of the Armory, which provided 80,000 square feet of unobstructed floor space (Image courtesy of “The Illio” 1915) and 1932 officers’ call inside the Armory (Image courtesy of “The Illio” 1932)

Detailed to the University in 1894 and appointed professor of military science and tactics, Captain Daniel Brush came to the rescue of the embattled Illinois Military Science program, putting it on an even keel after the previous decade’s disturbances. A Carbondale, Ill., native and a West Point graduate, Brush won the respect of the students, faculty, and most notably, University President Andrew Sloan Draper.

According to an effusive Draper, the captain was “an unusual man for getting on well with college boys. He has done more to popularize the military department at the University and to uplift the tone of honor among students since he has been here than anyone else connected with the University.”

During the subsequent presidency of Edmund Janes James (1904-20), the school’s military department prospered. According to a biographer, James held “a warm spot in his heart” for the University cadet corps because of his natural love of “pomp.” Under James, the military program finally received a suitable headquarters in the University’s new Armory. Completed in 1915, the Armory contained enough space for “the entire brigade to carry on its full schedule of drill no matter what the weather may be outside,” James said. He bragged that it was “the largest drill hall in the world.”

Top: The Engineering Corps erects a bridge during “The Sham Battle” of 1916, which pitted two regiments of the Illinois Corps against each other over control of the Crystal Lake territory. To simulate real combat, cadets fired blank cartridges at the opposing side. (Image courtesy of “The Illio” 1916); Bottom Left: Battery F, the Illini Battery, trains for deployment in Texas in 1916 in General John J. Pershings’ campaign to capture Mexican General Poncho Villa. (Image courtesy of “The Illio” 1918); and Bottom Right: 1924 members of the Army Air Corps and Signal Corps. (Image courtesy of “The Illio” 1924)

ROTC established at Illinois

Following the outbreak of World War I in July 1914, James, like Theodore Roosevelt, stepped up as a vocal advocate for greater military preparedness. James believed that the federal government should use land-grant universities to develop a reserve corps of much-needed Army officers. Testifying before a Congressional committee, the U of I president endorsed a program similar to what would eventually become the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps.

Thanks in part to the advocacy of James and others, the ROTC was created through passage of the National Defense Act of 1916, forever transforming the military programs of land—-grant universities. Under the provisions of the Defense Act, college students nearing the end of their sophomore year could choose to enroll for two more years of ROTC service. Those who made that choice were required to spend five hours a week in an advanced military science course and to attend two, four-week-long summer training camps. Students who completed the advanced course were eligible for appointment as reserve officers in the U.S. Army for 10 years.

The University of Illinois distinguished itself as one of the nation’s first colleges to apply to the War Department for an ROTC unit. In January 1917, the federal government gave the University the go-ahead to establish ROTC infantry, engineering and signal units. When the U.S. entered World War I several months later, however, the new ROTC program was put on hold because of the shortage of Army training officers.

In place of the ROTC, the Student Army Training Corps sprang up on hundreds of college campuses during the Great War. Intended to quickly churn out a supply of trained officers, experts and enlisted men for the armed forces, the SATC turned the University of Illinois into a “training camp” with close to 3,000 student soldiers by the fall semester of 1918. However, the end of the war in November 1918 terminated the unpopular SATC program, and many students rejoiced.

“Student Army Training Corps,” a frustrated poet at the University of Iowa quipped. “You sure made us awful sorps.”

The University’s ROTC program was re-established on Jan. 1, 1919, and reached its zenith the following decade. Boasting more than 3,000 cadets by the mid-1920s, the program gained a reputation as one of the nation’s largest. In 1919 and 1920, Illinois’ ROTC training curriculum expanded, adding field artillery, cavalry and air service units. The staff of the military department grew as well and by 1921 comprised 14 officers and 92 enlisted men.

During the rebellious 1920s, more and more students began to openly question the necessity of compulsory freshmen and sophomore military training, and The Daily Illini provided a forum for their discontent. The student newspaper ran a withering article written by a former Illini who took issue with a Chicago Tribune reporter’s contention that UI underclassmen were “nothing but overjoyed” by the prospect of drilling.

“Either the reporter didn’t know his business, or he was deliberately telling a lie,” the anonymous author wrote. “For, anyone with his eyes and ears open knows that a majority of the Illinois students object to military training.”

By 1925, the UI ROTC program numbered 3,000 cadets. Shown above are the full-time U.S. Army officers assigned to Illinois’ ROTC. (Image courtesy of “The Illio” 1926)

World War II boosts demand for officers

However, the debate over compulsory ROTC participation faded with the start of World War II. Since the ROTC’s debut in 1916, more than 4,000 Illini had taken the advanced military course and received Army reserve officer commissions. Many of them soon were called to active duty for WW II. Meanwhile, the ROTC accelerated its training efforts to meet the war’s gargantuan demands for personnel.

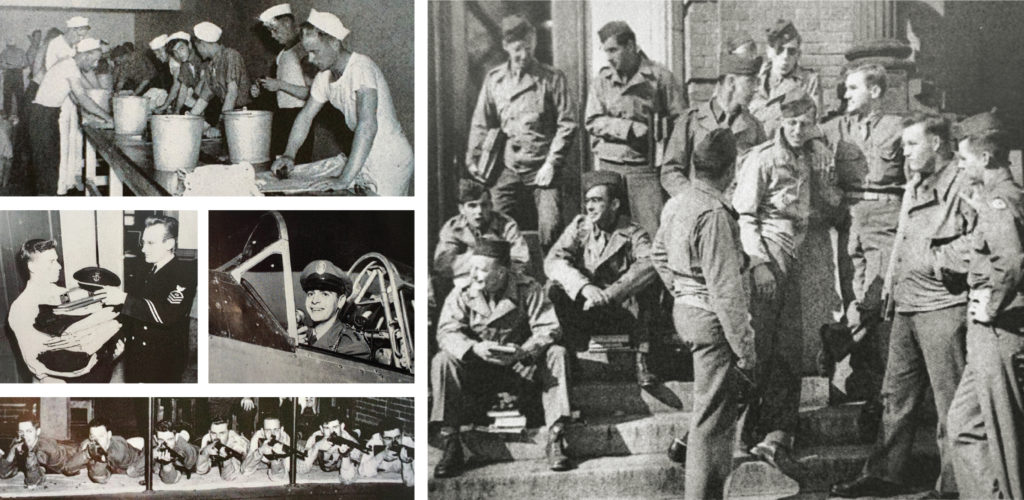

As the war progressed, the Army Specialized Training Program took over some ROTC functions. The ASTP was instituted on college campuses to supply the Army with men trained in medicine, engineering, languages, science, mathematics and psychology. Earlier, the U.S. Navy had established a U of I presence, organizing signal schools and training programs for cooks and diesel-engine operators.

During this timeframe, Illini women received military training for the first time in the University’s history. Wearing simple uniforms of brown skirts, blouses and ties, the U of I’s Women’s Auxiliary Training Corps drilled without weapons and received instruction in such subjects as military customs and courtesy, sanitation, first aid and map-reading. The WATC program disbanded after less than a year, however, due to a lack of interest.

Left Top: During World War II, the U.S. Navy established training programs at Illinois for cooks and diesel-engine operators. (Image courtesy of “The Illio” 1944); Left Middle: In 1945, the Navy set up an ROTC program, with the U.S. Air Force following suit in 1949. (Image courtesy of “The Illio” 1949 and “The Illio” 1953); Left Bottom: 1949 also saw the Illinois Army ROTC rifle team defending their championship title in the Fifth Army intercollegiate rifle matches. (Image courtesy of “The Illio” 1949); and Right: To help address the shortage of men trained in the fields of medicine, engineering, languages, science, mathematics and psychology during WWII, the U.S. War Dept. established the Army Specialized Training Program. Nearly 4,500 men participated in the program at Illinois. (Image courtesy of “The Illio” 1944)

Following the conclusion of WWII, the University enjoyed record enrollments and so did the school’s ROTC program. A Naval ROTC unit was founded on campus in 1945, followed by an Air Force ROTC unit in 1949. Although these programs thrived during the 1950s, compulsory ROTC training was, in fact, on its last legs. Toward the end of the decade, one land-grant college after another phased out mandatory military training. Student protests played a role in the movement but by no means a decisive one.

“There is no question … that a great deal of the impetus relative to elimination of compulsory ROTC has emanated from student groups,” George Bargh, executive assistant to UI President David Henry, explained to a news correspondent early in 1960. “However, the fact is that the faculties, colleges and universities are really responsible for the successful campaigns to place ROTC on a voluntary basis.”

University administrators stated that the quality of ROTC classes was “not of college level.” They were further displeased with the amount of space required by ROTC facilities—space that was increasingly needed as enrollments soared.

On Dec. 18, 1963, the University of Illinois Board of Trustees closed the book on almost 100 years of student military history and made armed forces training voluntary at Illinois, effective Sept. 1, 1964. The U of I was one of the last big land-grant colleges to abolish mandatory ROTC training.

Although no longer compulsory, ROTC continues to be a respected University offering.

“Some may question the need for ROTC programs at institutions such as Illinois,” says Joe Rank, ’69 MEDIA, MS ’73 MEDIA, past vice president of the University of Illinois Alumni Alliance and a retired U.S. Naval officer. “I contend both the need and mutual benefit are greater than ever. While we no longer need the sheer numbers of officers we turned out between 1867 and 1963, our nation continues to benefit from the exceptionally bright, dedicated, liberally educated and worldly citizen soldiers who are commissioned each year through Illinois’ three ROTC programs.”

Duty Calls

Quick takes on ROTC today at Illinois

U.S. military branches with ROTC programs at Illinois: All

Undergraduates engaged in Air Force, Army or Navy/Marine Corps ROTC training on campus: 237

ROTC-related study carries: Up to 23 academic credit hours

Weekly time commitment for ROTC activities: Eight hours minimum

Financial support: A monthly stipend, and for many, federal, state and University scholarships and grants

Students in Army and Air Force ROTC are: Cadets

Students in Navy/Marine Corps ROTC are: Midshipmen

Long-time campus home of ROTC: The Armory

Summer ROTC activities: Foreign language immersion, leadership training with active-duty units, air assault and airborne schools, internships, exchange programs and, for midshipmen, a month or two at sea aboard Navy vessels

Minimum post-graduation military service required of ROTC-trained officers: Four years for Army and Air Force; five years for Navy/Marine Corps

Number of Army, Navy, Marine and Air Force officers who received commissions upon graduation from Illinois in 2018: 52

DID YOU KNOW…

UI midshipmen ring the Memorial Stadium bell that marks the opening of home football games and points scored by the Fighting Illini. The bell was salvaged from the USS Illinois, a World War II battleship.

In 2015, the Army ROTC battalion returned the flying of “Old Glory” to its place above the Armory, restoring a flagpole that had been out of use for 40 years.

UI’s Air Force ROTC Detachment 190 is known as the “Home of the Flying Illini.”