Ingenious: Did exploding supernovas cause mass extinction?

A new study led by U of I Astronomy and Physics Professor Brian Fields explores the possibility of astronomical activity leading to an extinction event that occurred 359 million years ago during the Paleozoic Era. His team concentrated on studying rocks from the boundary between the era’s Devonian and Carboniferous periods because those samples contain hundreds of thousands of generations of plant spores that appear to be sunburnt by ultraviolet light—evidence of long-lasting ozone depletion.

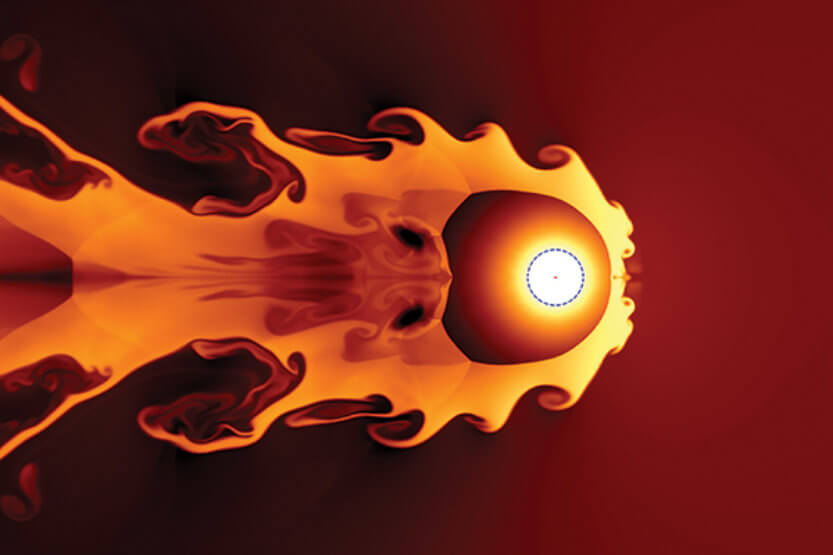

“We propose that one or more supernova explosions, about 65 light-years away from Earth, could have been responsible,” Fields says of the findings published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

“To put this into perspective, one of the closest supernova threats today is from the star Betelgeuse, which is over 600 light-years away and well outside of the kill distance of 25 light-years,” says graduate student and study co-author Adrienne Ertel, MS ’18 LAS.

The team explored terrestrial and other astrophysical causes for ozone depletion, such as meteorite impacts, solar eruptions and gamma-ray bursts. “But these events end quickly and are unlikely to cause long-lasting ozone depletion,” says Jesse Miller, U of I graduate student and study co-author.

A supernova, on the other hand, delivers a one-two punch, according to researchers. The explosion immediately bathes Earth with damaging UV, X-rays and gamma rays. Later, a blast of supernova debris slams into the solar system, subjecting the planet to long-term irradiation. The damage can last for up to 100,000 years.

However, fossil evidence indicates a 300,000-year decline in biodiversity leading up to the Devonian-Carboniferous mass extinction, suggesting the possibility of multiple catastrophes, maybe even multiple supernovae explosions.

“Life on Earth does not exist in isolation,” Fields says. “The cosmos intervenes—often imperceptibly, but sometimes ferociously.”