Ingenious: Eureka Moment

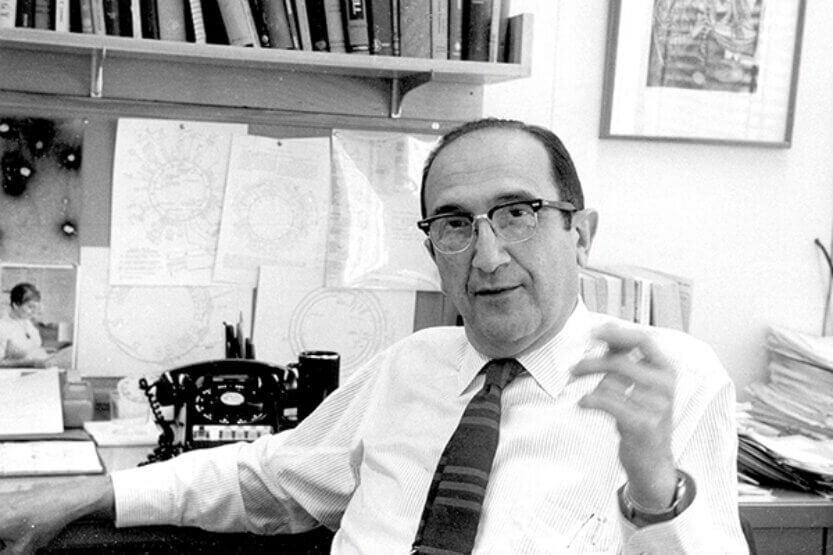

Microbiologist Salvador E. Luria also was known for his political activism, including opposition to the Vietnam War. (Image courtesy of the U.S. National Library of Medicine)

Microbiologist Salvador E. Luria also was known for his political activism, including opposition to the Vietnam War. (Image courtesy of the U.S. National Library of Medicine) Salvador E. Luria’s breakthrough research on bacteria and genetics can be traced to a chance encounter on a stalled trolley in Rome during which he struck up a conversation with bacteriologist Geo Rita, who told him about his work with bacteriophages—viruses that infect bacteria.

Luria would go on to devote much of his early research to these “phages.” His studies transformed genetics and “contributed to the foundation on which modern molecular biology rests,” according to his 1991 obituary in The New York Times.

Born in Turin, Italy, Luria planned to work on phages in the U.S. under an Italian fellowship in 1938. But the day after he received the award, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini’s Racial Manifesto went into effect, blocking Luria from accepting the fellowship because he was Jewish.

Luria left Italy to work in Paris. But as the German army marched toward the city in 1940, he had to flee again, this time by bicycle to Portugal, eventually finding his way to the U.S.

By 1942, he was working with biophysicist Max Delbrück at Vanderbilt University, where they began tackling the question of whether phages directly produce mutations in bacteria, or whether those mutations are spontaneous and random.

In 1943, Luria had a “eureka moment” watching a colleague win a slot-machine jackpot. He and Delbrück hypothesized that, like payouts on a programmed slot machine, mutations occurred randomly in bacteria exposed to phages. Their theory of “mutational jackpots” led to the landmark Luria-Delbrück Fluctuation Test. It also “marked the birth of bacterial genetics,” according to a National Institutes of Health profile on Luria.

Luria ultimately shared the 1969 Nobel Prize with Delbrück and Alfred Hershey for their pioneering discoveries about the genetic structures and replication mechanism of viruses.

Luria joined the U of I faculty as a professor of microbiology in 1950, where he learned that some phages grew well in certain host bacterial strains, but poorly in others. His observations of “restricted” phage growth were a crucial contribution to the later discovery of “restriction enzymes,” which became a vital tool in recombinant-DNA technology, or genetic engineering.

Luria also was well-known for his political activism, including his opposition to the Vietnam War. In fact, days after winning the 1969 Nobel Prize, his name was put on a federal funding blacklist.

The ban was ignored.

Sources: “Salvador E. Luria is Dead at 78,” The New York Times, Feb. 7, 1991; “Genetics Lessons from Bacteriophage, 1938–44,” the National Institutes of Health; “Salvador E. Luria, MD, Brief Bio,” the American Association of Immunologists.