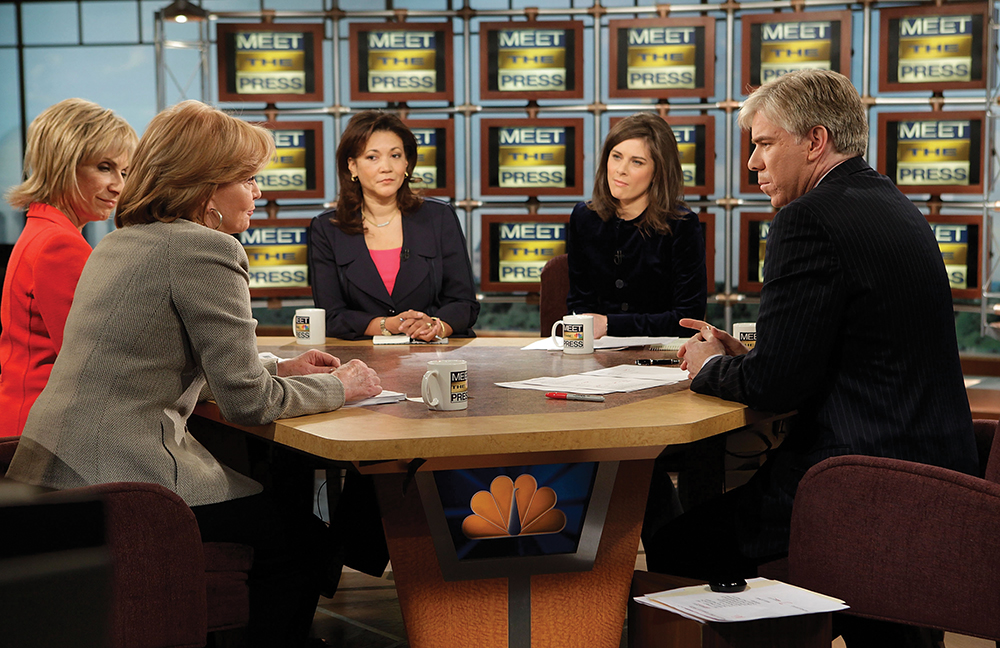

One in a million

Carol Marin (Image by Kate Schleicher)

Carol Marin (Image by Kate Schleicher) The November presidential vote might have confirmed a deep rift in the American psyche, but in Chicago, there was total unanimity. With the possible exception of corrupt politicians, anyone who has ever watched TV news programming saluted Carol Marin, ’70 LAS, when she announced she would be leaving the broadcast news business immediately after Election Day.

“When you look at the body of work she’s done, she’s the gold standard,” says Phil Ponce, who shared the anchor desk with Marin at Chicago’s PBS affiliate, WTTW. “There’s a phrase in Latin—‘sui generis.’ Carol was one of a kind.”

“Absolutely the best, there was no one like her,” agrees Mary Ann Ahern, Marin’s newsroom pal at Chicago’s WMAQ-TV, and half of their self-proclaimed “Thelma and Louise” team. “She was one in a million, a trillion.”

“We were together a long time but not long enough,” says Ron Magers, who co-anchored the WMAQ nightly broadcast for 13 years with Marin.

Her post-election retirement had nothing to do with the pandemic and nothing to do with who won or lost the election. It was a long-planned capstone to an extraordinary career.

“I’ve seen too many people stay too long,” Marin says. “So I made up my mind I was going to call my shot when I still loved the work and it was solid.”

Solid would be an understatement. Over her almost five decades in the broadcast news business, Marin has won just about every award imaginable, some many times. A paladin of civic rectitude, she grilled governors and tracked mobsters. Presidents and cardinals hailed her by name. She broke the story on the federal corruption investigations Operation Gambat and Operation Silver Shovel.

Few public officials escaped their fate in the Marin crosshairs. She made Chicago mayoral candidate Jesus “Chuy” Garcia, ’98 UIC, MUPP ’02 UIC, squirm as he tried to duck the subject of his payrolled cousin. When Rahm Emanuel responded to a debate question on what he would do as a second-term mayor and responded with his patented, “Let’s take a look back at what I’ve done,” Marin cut him off: “No, let’s look forward.” After a nervous chuckle, the mayor did what she asked.

A journalist by happenstance

Marin never intended to go into television news. At Illinois, she majored in English and lived for the debate team. “It makes you learn how to think; it [makes you] explore all different sides to a question,” she explains.

After graduation, she taught high school English in Carpentersville, Ill., then moved to Knoxville where her husband joined the history department at the University of Tennessee. When no teaching jobs materialized, friends suggested she try for a just-vacated local TV talk-show spot, despite her husband’s doubts. “Maybe you’re afraid of [doing] that,” he dared her.

“It was all he had to say to me,” Marin says.

On the set, Marin was told she would audition for the job by interviewing a fictitious film producer, played by a devoutly religious man who worked in the station’s videotape room. “He whispered, ‘Honey, they told me not to answer any of your questions,’ so I introduced him as a pornographer, which got him so nervous he started talking, and they hired me because I’d amused them,” Marin recalls.

She moved to WSM-TV in Nashville in 1976, where she did a series of stories on Tennessee Gov. Ray Blanton, who lavished perks on his cronies and was accused of selling pardons and paroles. Figuring to brush the rookie reporter aside, he agreed to an interview with Marin and “came on air to ostensibly lynch me and brought a planeload of his cabinet with him,” she recalls. “His performance during that interview melted down our phone lines and led to his demise. He was my first governor.”

“I’m not an advocate reporter. My job is to tell a story and let the public get outraged.”

The Blanton interviews caught the attention of WMAQ-TV, which offered Marin a reporting and weekend news-anchor job in Chicago. Within months, she was teamed with Magers on the 6 p.m. and 10 p.m. weeknight anchor desk.

“Athletes will tell you that it increases your confidence to have someone equal or better on your team,” Magers says. “I always thought Carol was smarter than me. She was a much better reporter. Anyone in our newsroom would have purchased her contact book for any amount of money.”

“She’s got every darn number under the sun,” Ahern says. “Her phone belongs in the Smithsonian!”

Her contacts were legendary, and Marin often took great care to protect her sources from snooping feds. For one high-wire story, she had her producer deliver the tipster to his garage to avoid being identified. If nervous sources couldn’t be phoned, she’d wear her trademark red glasses to signal that they needed to contact her. Thanks in part to Marin’s reporting chops, WMAQ stayed a “solid No. 2” in the ratings for years.

She and Magers might have stayed on for a few more decades if the station hadn’t tapped Jerry Springer, the incendiary star of his own talk-show slugfest, to provide commentary on the 10 p.m. news in 1997. For Marin, it was the last straw in a toxic relationship with station management that she accused of “marketing our news stories to clients to make them seem less commercial.” Magers took a months-long break to golf, and Marin signed on with CBS in New York City.

(Clockwise from the top) Carol Marin winning a Peabody Award with her long-time producer, Don Moseley (Image courtesy of Carol Marin); leading a discussion with journalists Lester Holt and Ben Welsh at DePaul University’s Center for Journalism Integrity & Excellence (Image courtesy of DePaul University/Jeff Carrion); interviewing President Barack Obama (Image courtesy of Carol Marin) and reporting on the collapse of second World Trade Center at CBS News (Image courtesy of CBS News).

She was there on 9/11, rushing toward the World Trade Center, when the second tower came down. Sprinting to escape, she tripped and fell, saved by a firefighter who protected her with his body. Together, they stumbled blind through the hail of debris. Hours later, her clothes still covered with soot and ash, she recounted the harrowing ordeal at the anchor desk with Dan Rather.

Unscripted reporting was the exception. Mostly, Marin had a text and most were written with her longtime producer/collaborator Don Moseley. Producer and reporter teams were not unheard of in television, but few, if any, lasted as long or had as much of an impact as Marin and Moseley. Ask Moseley about who did what on their broadcast and you get a dutiful, fascinating answer about story “discovery,” first drafts, editing and Marin’s battles for more on-air time. The seed of their teamwork began in the Nashville WSM-TV newsroom where they met, and the place Moseley credits for instilling a belief that, for people in power, accountability comes with the territory.

“We were taught that when you’re running for public office, you should expect to be held to a higher trust,” Moseley says. “Part of journalism is holding their feet to the fire.”

That mission accounts for Marin’s tenacity as a reporter and her tough stance on election panels. But there was another side to her work, too, one that looked for the humanity in stories and sought out people who’d been ignored or discarded by society.

“What a lot of people don’t pick up on is her empathy,” Ponce says. “She’s one of the most compassionate people I know. It’s one of her strengths as a journalist. She hates to see people taken advantage of. Fairness gets to her at a level that’s visceral.”

None of Marin’s stories fit that bill better, or were more wrenching, than her reports on Guinevere Garcia, a young mother convicted of smothering her 11-month-old daughter in 1977 then later killing her husband in 1991.

Marin was outside the Stateville Correctional Center in Joliet, Ill., covering John Wayne Gacy’s execution when Moseley remarked, “You know, there are five women on death row.” Marin wrote letters to each one, but it was a year later before Garcia’s lawyer responded: She wants to talk. Marin’s subsequent taped reports from prison revealed a deeply damaged woman who’d suffered years of sexual abuse. Marin’s pieces stirred worldwide public support—Amnesty International activist Bianca Jagger flew in to lobby for Garcia—but Garcia refused to fight her own execution and was hours away from a lethal injection when the phone rang at Marin’s home.

“As long as I’ve been a reporter people have accused the media of having an agenda.”

“I picked up and heard [from the station], ‘Get in here, [Gov. Jim] Edgar stayed the execution,’ so I jumped on the news desk with Ron,” Marin says. “We were the only people who had video. To this day, I talk with her all the time.”

Memorable in a different way was the saga of Joel Sonnenberg, a 4-year-old who was horribly burned at age 2 when a 40-ton tractor trailer hit his family’s car, which exploded in flames. Marin stayed on the story for 20 years, chronicling how Sonnenberg’s disfigurement affected his life and how he triumphed over it. Her final piece about him on Public Eye With Bryant Gumbel won Marin and Moseley a Peabody Award for CBS.

Marin’s confessed “Big Three” favorite reporting topics—corrupt politicians, mobsters and prisons—might have suggested a hard-core crusader, which Marin was, but away from the camera she presented a very different persona.

An instantly recognizable face, she fiercely guarded her privacy and left celebrity status to others; her occasional fill-in for Jane Pauley on NBC’s Today show brought a sense of accomplishment, but she was ready to pack her bags for Chicago on Friday. Those closest to Marin know her as a totally unpretentious woman, always approachable, a fun, spontaneous colleague and a hugely generous friend.

Ahern first met Marin when she spotted her at a Texas airport while covering the 1988 Democratic convention. “I thought, ‘Omigosh, there’s Carol Marin!’ ” Ahern recalls. “I just beelined over and said, ‘I want to work in Chicago! Can I send you my tape?’ ” Three months later, Ahern was on the payroll.

“We’re not all so great to each other in this business,” Ahern admits. “Even in our own newsroom, it’s often who wants to be first or who gets to scoop everybody. Carol’s not that way at all. She’s always willing to give you contacts and information. Marin’s encouragement also could extend to strangers who were still too young to be in the business. Andrea Darlas, ’94 MEDIA, now a senior director of constituent engagement at Illinois, was a 16-year-old high school student when she called to interview Marin for a journalism class.

“She picked up and said, ‘Marin,’ ” Darlas recalls. “She asked about my deadline, apologized that she was on deadline and said to call her back in five minutes. Then she talked [to me] for 30 minutes, I kid you not! When I got hired at WGN Radio, she sent me a handwritten note of congratulations. When I became the morning news anchor, she sent another handwritten note. It was so rare to meet her as a teenager, then have her go from mentor to colleague to friend.”

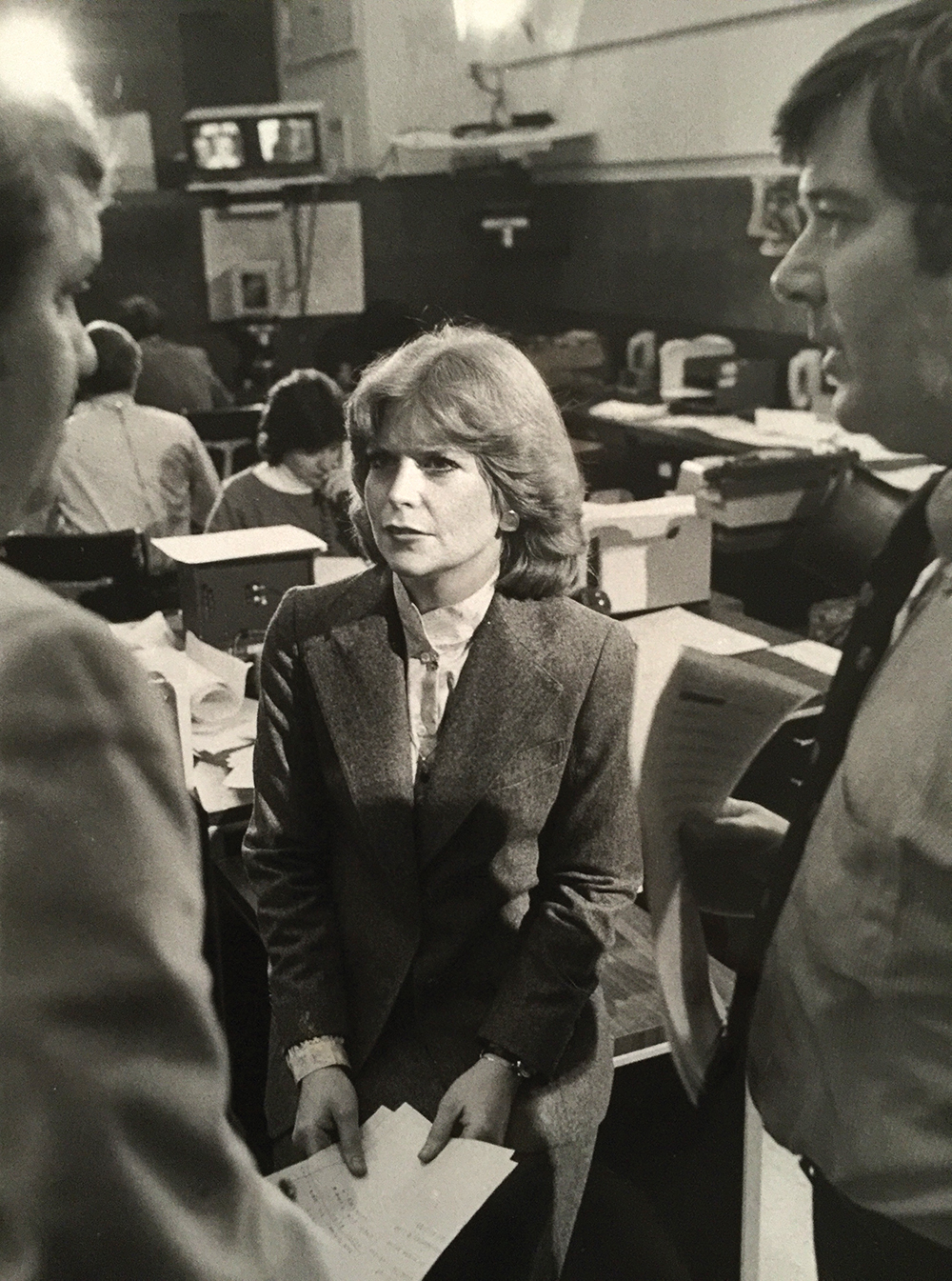

After stints at WBIR-TV in Knoxville, Tenn., and WSM-TV in Nashville, Marin joined Chicago’s WMAQ-TV in 1978 as a reporter and weekend news anchor. Soon, she was co-anchoring the 6 p.m. and 10 p.m. newscasts, and breaking stories like the ones about the federal government’s corruption investigations, Operation Gambat and Operation Silver Shovel. (Image by R.B. Leffingwell/Chicago Sun-Times)

Public’s distrust of media

Despite Marin’s tough exposes on organized crime and corrupt politicians, she is not an angry person. “I’m not that kind of reporter,” she explains. “I’m not an advocate reporter. My job is to tell a story and let the public get outraged.” She is not even outraged by attacks on the media that have sucked up so much attention over the past few years. Cries of “Fake news!” and the disparagement of print and broadcast news have not soured her on the future of journalism. That negative viewpoint, she insists, is nothing new.

“People have mistrusted the media for decades,” Marin says. “As long as I’ve been a reporter, people have accused the media of having an agenda. When I was doing interviews with evangelicals during the Bush administration, people didn’t want to talk to us because CNN was the ‘communist news network.’ Barry Goldwater, Phyllis Schlafly and Curtis LeMay all thought we were some left-wingers perverting the news. It’s always been like that.”

The problem, as Marin sees it, is the public’s lack of “media literacy.” Too many people don’t distinguish between NBC, say, and MSNBC. The latter is filled with opinion and talk; the former does reporting. Fox News may have seemed to be the Trump mouthpiece, but Marin points out that it also has a news organization.

Nor is she one to condemn social media. It’s only a “delivery system,” Marin says, “and it would be a mistake to throw out the baby with the bathwater. Maggie Haberman [of The New York Times] is a superb reporter, but she also does trenchant tweets. You have to be ready to do it all.”

Her optimism that young journalists can do just that and do it right is fueled at Chicago’s DePaul University where she and Moseley co-founded the school’s Center for Journalism Integrity & Excellence, whose select students have produced stories for Chicago Tonight on everything from the pandemic and poverty to car-booting companies. Marin’s immediate audience may have shrunk from hundreds of thousands to a single small classroom, but that’s more than enough to sustain her faith in the future.

“Do I sense any hope? Yeah! It’s why those students are in the program. They believe in journalism. Absolutely!”