Alumni Interview: Kerry Joels

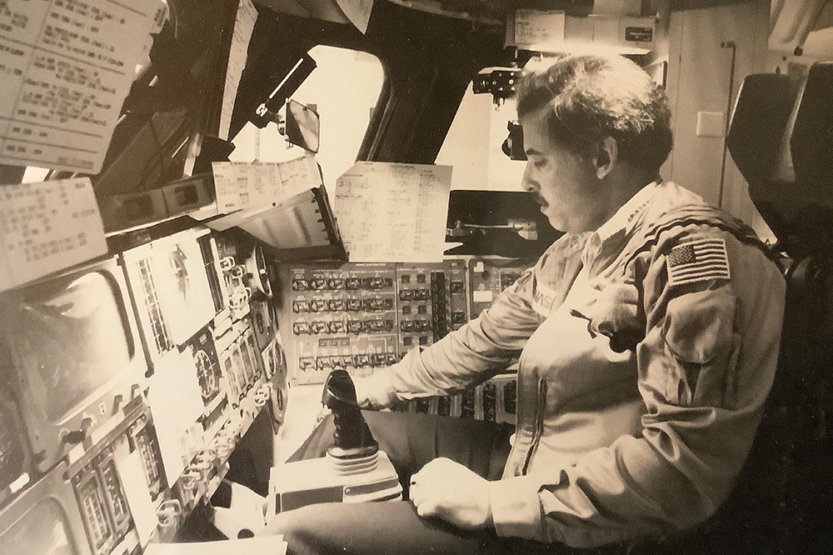

“Humans are explorers. We are driven to expand our frontiers,” says Kerry Joels, MA ’68 LAS, former curator of Space Science, Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. (Image courtesy of Kerry Joels)

“Humans are explorers. We are driven to expand our frontiers,” says Kerry Joels, MA ’68 LAS, former curator of Space Science, Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. (Image courtesy of Kerry Joels) Growing up as a child actor in New York, I won a role in the animated movie The Space Explorers. That hooked me on astronomy, so I soon retired from acting and wound up majoring in physics at Principia College [Elsah, Ill.]. Planning to teach college astronomy, I applied to Illinois’ graduate History of Science program.

It was on the Champaign-Urbana campus, with its world-class faculty, that I honed my research skills and enjoyed incredible access to cosmologists, historians—and even lasers! I also spent long hours transcribing astronomy treatises from the 17th and 19th centuries, which builds character.

In 1970, NASA, suitably impressed by my master’s degree from Illinois, recruited me for a doctoral program that combines aerospace and education. I made my way to NASA’s Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley and enjoyed working on space projects that seemed futuristic at the time. Equally exciting was working with actress Nichelle Nichols to bring diversity to the ranks of American astronauts. That’s how Star Trek’s Lieutenant Nyota Uhura and I became friends for life.

In 1978, I became the founding director of the Education Division at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. That led to the post of curator there—and my Illinois training really kicked in. The job was a privilege that called for every ounce of historical knowledge and tech expertise I had. It left just enough spare time for me to knock out a bestselling book, The Space Shuttle Operator’s Manual.

It was on the Champaign-Urbana campus, with its world-class faculty, that I honed my research skills and enjoyed incredible access to cosmologists, historians—and even lasers!

Tapped by the White House in 1984, I led a blue-ribbon panel that founded the nation’s Young Astronaut Program. Then, after the tragic Challenger accident that killed Christa McAuliffe and six other astronauts, I helped the crew’s families create the Challenger Center for Space Science Education, which simulates astronaut experiences for students nationwide as well as in Canada, the U.K. and South Korea. Thirty years later, more than 40 Challenger Centers serve more than 400,000 students every year. At every turn, I’ve employed the skills I honed at Illinois in an effort to think, communicate and work with purpose, success and even joy.

I’m often asked about the space program, which has been back in the news lately. Part of my work at the Smithsonian was devoted to what we called Future Studies, a historically oriented look at such questions. We found that public opinion about the space program was remarkably stable from the 1960s through the ’80s. One-third of the country—I’ll call them the Trekkies—were committed to human spaceflight as a final frontier, a sort of manifest destiny. Another third was unalterably opposed to it, convinced that we should spend the same money to improve life on Earth. The other third flipped situationally.

As a member of a White House commission on future missions to the Moon and Mars, I found myself debating Carl Sagan before a professional meeting in Virginia. He claimed that only robots should fly rockets into space. I argued that people wouldn’t care as much unless real flesh-and-blood people flew, too. Neither Carl nor I scored a knockout, but after we finished I was pleased to hear a congressional staffer who ran NASA’s budget tell him, “Carl, without the sizzle of a manned space program, I can’t get you a billion dollars for your robots!”

Today, interestingly, we are having the same debate. NASA’s Artemis program to the Moon, the Space Launch System super-rocket and the Orion spacecraft are making news, while private-sector partners like SpaceX and Blue Origin bring ambitious projects of their own. I think we’re going to see another lunar landing. If we don’t go back to the Moon, the Chinese will. Next will come a crewed flight to Mars, probably in the 2030s.

Humans are explorers. We are driven to expand our frontiers. Exploring the world, and ultimately the universe, isn’t just what we do. It’s who we are.

Now is no time to stop flying—not when there’s so much out there to discover.