Baptism by fire

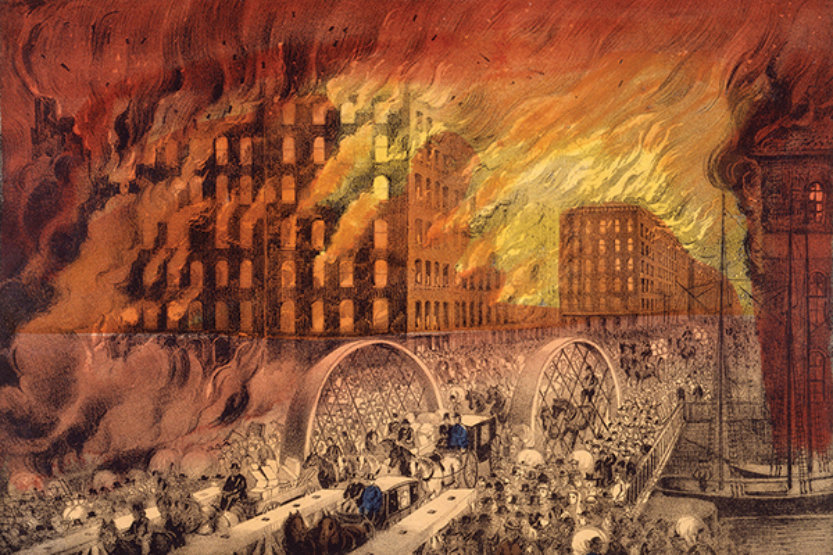

Chicago fire, 1871 (Image courtesy of Currier and Ives)

Chicago fire, 1871 (Image courtesy of Currier and Ives) The train from Champaign lumbered through the black Illinois night, just past the witching hour, en route to a city on fire. Nineteen-year-old Dillon Brown, Class of 1875, sat in his seat, smelling the wood smoke of the locomotive, listening to the iron-on-steel clack of the train on the tracks, too excited and nervous to sleep. His destination: Chicago, “the Garden City of the West,” which had been burning for three days in what was already one of the most famous blazes in American history, the Great Chicago Fire of Oct. 8-10, 1871.

Brown wasn’t traveling alone. He was a cadet in the Illinois Industrial University’s military battalion, and on the train with him were 156 fellow cadets, ready to serve the state university that would one day become the U of I.

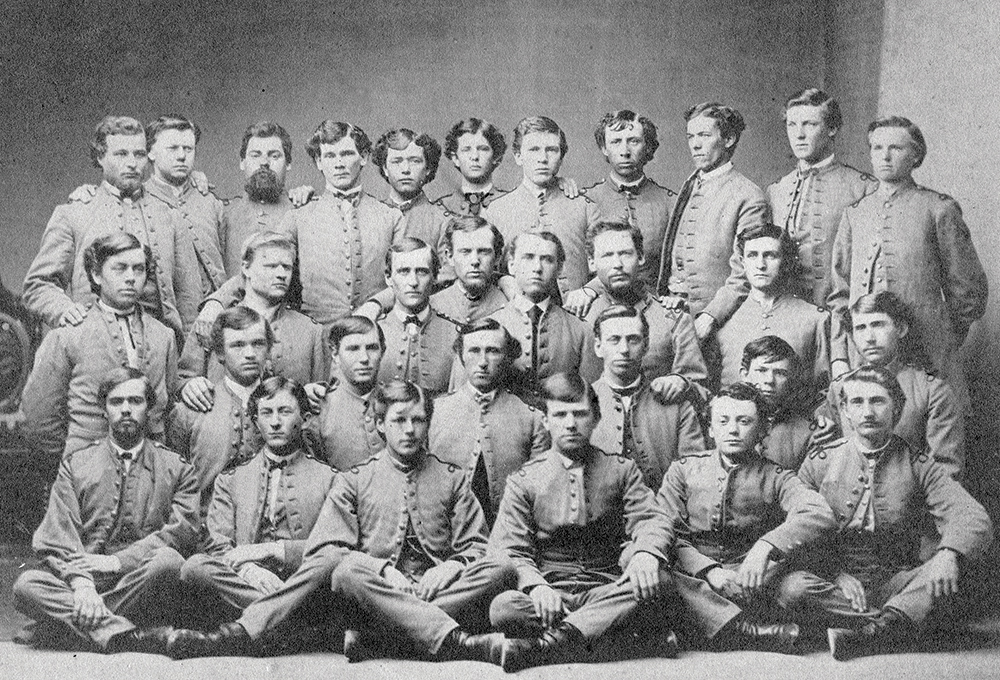

Maybe you can picture them: scores of young men, all white, many of them Illinois farm boys, some on a train for the first time, dressed in the rough gray wool of their cadet uniforms. They have been called up by Illinois Gov. John Palmer as part of an historic relief effort for the 100,000 Chicagoans who had lost their homes overnight. Like Dillon Brown, they are excited and nervous, wondering what the next days will hold—about the challenges that await them, and whether they’ll be up to the task.

By the time their train arrives in Chicago, just before dawn on Oct. 11, the Great Fire has been extinguished for nearly 24 hours, though the embers will continue to smolder for days afterwards.

When the cadets get off the train, they observe the remnants of a wooden city: three square miles of ash and charred timbers, a few surviving structures bearing witness, and boulevards trodden black by the hundreds of thousands of Chicagoans who fled in terror as the wooden streets and sidewalks literally burned behind them.

The cadets had fought many fires as part of their military duties—in fact, they had battled one earlier that week that had destroyed most of downtown Urbana—but they had never seen anything like the ruins of Chicago. Just days before, the city had been a beacon of progress, the industrial center of the new Midwest. And yet, in a matter of hours, it had become a land of desolation, felled by a dry summer, a strong wind and a spark that grew into an inferno, killing more than 300 people.

Fortunately, the still-new invention of the telegraph had enabled city officials to spread word about the fire as it was burning. Somehow, Chicago’s famous railroads and ports had remained mostly undamaged, making it possible for aid to reach the city quickly, from all over the world.

From the moment the cadets stepped off the train, they were in for three days of intense service. First, they reported for duty at what is now Union Station, where Lt. Gen. Philip Sheridan—the Civil War hero whose cavalry had forced Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox—gave them their orders and sent them on their way, but not without calling them the “best-looking, best-drilled battalion in the city.”

Sheridan split the cadets into two groups. One was assigned to patrol duty on the South Side, stationed at the corner of Prairie Avenue and 22nd Street (now Cermak Road), where it helped federal troops and local police transport people to safety, prevent theft and property damage, and promote peace. It also enforced the mayor’s emergency orders that were meant to ensure public safety and stop unscrupulous business owners from exploiting the downtrodden. Among the orders were those that banned smoking (for obvious reasons), fixed the price of bread and other staples, and prohibited horse-drawn wagon drivers from raising their rates, as panicked residents hired carts to move their remaining possessions.

The second group of cadets was stationed at the corner of West Randolph and Ada streets, where it guarded the West Side Rink—a community ice arena turned disaster supply house—and helped to distribute food, water, medicine, blankets, clothing and camping supplies.

Dillon Brown recalled the disorder at both the rink and the Ada Street Church, where thousands of displaced and desperate Chicagoans stood in line for free railroad passes out of the city. It was Brown’s responsibility—armed with a muzzle-loading, bayoneted, old Army rifle—to keep them in orderly lines and to prevent fights. People at the church were so famished, he recalled, that when an aid cart stopped and “tossed out” bread, “they grabbed and ran like a pack of hungry dogs.”

On the afternoon of Oct. 13, additional troops arrived to replace the cadets, and their service was done. Exhausted, they marched to the train station on their “pretty sore feet” and were back in Champaign that night—back to the insulated, daily routine of life on a college campus.

As for Chicago? Within weeks, its residents had banded together to clean up the city and to make way for the next chapter in its history.

In the end, the fire provided Chicago with an opportunity to renew itself, with a larger downtown, taller (stone and brick) structures, stricter building codes, and more clearly defined commercial and residential districts, setting it on the path to grow into one of the world’s great cities.

For the rest of their lives, those 157 Illinois cadets could take pride in knowing that they had played a small, but important, role in that story.