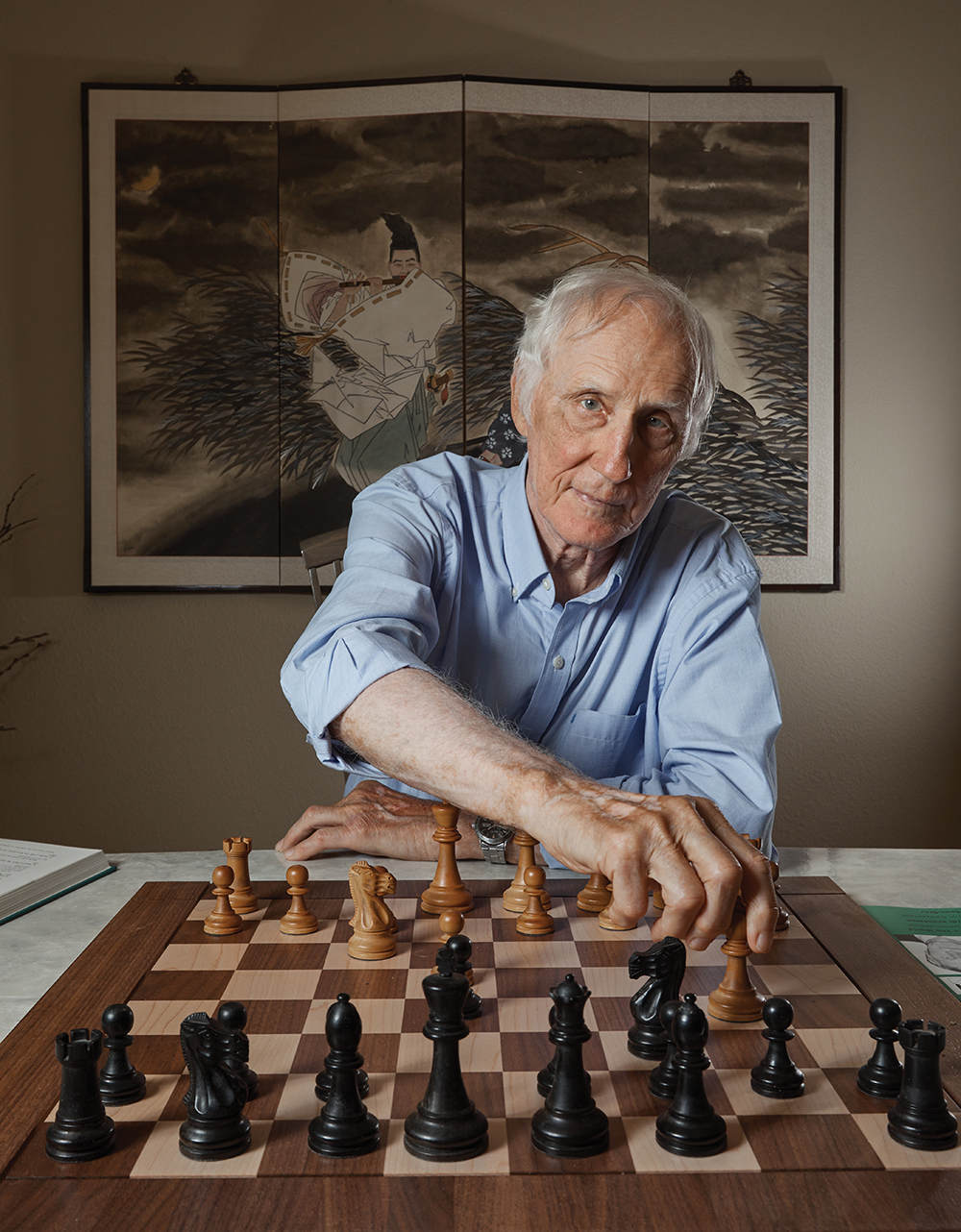

Chess King

Although the most cerebral of games, chess is lodged in the physical world: the site of the match, the pieces, the players squaring off across a board. But apart from a handful of unobtrusive post cards, correspondence chess—a long-distance competition form of the game—takes place entirely in the mind.

In 1982, Vytautas “Victor” Palčiauskas, ’63 ENG, MS ’64 ENG, PHD ’69 ENG, became the 10th World Correspondence Chess Champion; today he is the venerated elder in the International Correspondence Chess Federation and its lore, as well as a member of the World Chess Hall of Fame.

Born in Lithuania, Palčiauskas was introduced to chess by his grandfather. As a Chicago high school student, Palčiauskas became a rising star in the junior leagues of what correspondence players call in-person, “over-the-board” chess. The only qualm he had about studying theoretical physics at Illinois was that Champaign-Urbana was hardly a world-chess center.

That hurdle was overcome by an article in Chess Life magazine about Hans Berliner, the eminent computer scientist and chess master. While reading about how the Pittsburg-based Berliner had become the fifth world champion of the International Correspondence Chess Foundation, Palčiauskas says his mind began working overtime. “I was absorbing what I was reading and visualizing the events,” he recalls. Soon, Palčiauskas was playing chess by mail nearly every day, as many as 50 games at a time.

Correspondence chess requires specific skills. Reading the expressions and body language of an opponent is moot; focus is paramount. Says Palčiauskas: “You play your first move—which you then send to your opponent, usually by post card. Your opponent replies. You take up to three days to analyze that countermove, make your next move and mail it back.” A match of 10 moves per player can take up to 30 days.

Palčiauskas still plays an occasional “over the board” match. His opponent on this day

is 11-year old Ian Teng, a member of the U.S. Chess Federation. (Image by Peter Prado)

“You play your first move—which you then send to your opponent. Your opponent replies. You take up to three days to analyze that countermove, make your next move and mail it back.” —Victor Palčiauskas, ’63 ENG, MS ’64 ENG, PHD ’69 ENG

Palčiauskas’ lengthy trek to the World Correspondence Chess championship began in 1970, as one of thousands who entered a series of three tournaments. When the preliminary rounds ended, he was one of 16 remaining.

Next came a complex round robin competition in which everyone plays everyone else simultaneously. The tournament commenced in 1978 and ended four years later with Palčiauskas on top. Congratulations poured in from around the world.

A year after winning, Palčiauskas left his teaching job at the University of Illinois, resettling with his wife Aurelia in California where he had an offer to do research for Chevron and, later, the U.S. Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board.

After reaching the top of the heap as Grand Master, Palčiauskas continued to compete; in 2003, he tied for second place in a “champion of champions” tournament, the ICCF 50 Years World Champion Jubilee. Now a spry 80, Palčiauskas occasionally plays in-person opponents and keeps in contact with his chess pen pals. “Correspondence chess has played a major role in my life,” he says, “providing joy, sometimes grief, but always excitement.”