Being Black At Illinois

Illinois’ Black students have always built strong communities to help them survive and thrive on a predominantly white campus. Here, a group of fraternity and sorority members enjoy the Black All-Greek Picnic in 1955. (Image by Marie L. Johnson/University of Illinois Archives)

When the University of Illinois celebrated its 100th anniversary in 1968, only 1 percent of the student body was Black. African Americans had been on campus for nearly all of the University’s history—through its transformation from a backwater agriculture and engineering school into a world-class research institution; through the invention of electric lights, automobiles, movies, radio and television; through world wars and the Great Depression; through the Nuclear Age and the Space Race. Black students at the U of I had seen and heard it all. And yet: 1 percent.

This is a story about the experiences of Black students at Illinois, in the decades leading up to that 1 percent and in the decades since.

It is a story about courage, determination, discrimination, community and the struggle for equity in education that began the moment the first Black student stepped foot on the campus and continues in the present day.

It begins, as so many U of I stories do, on the first Monday in March 1868.

Black History Begins at Illinois

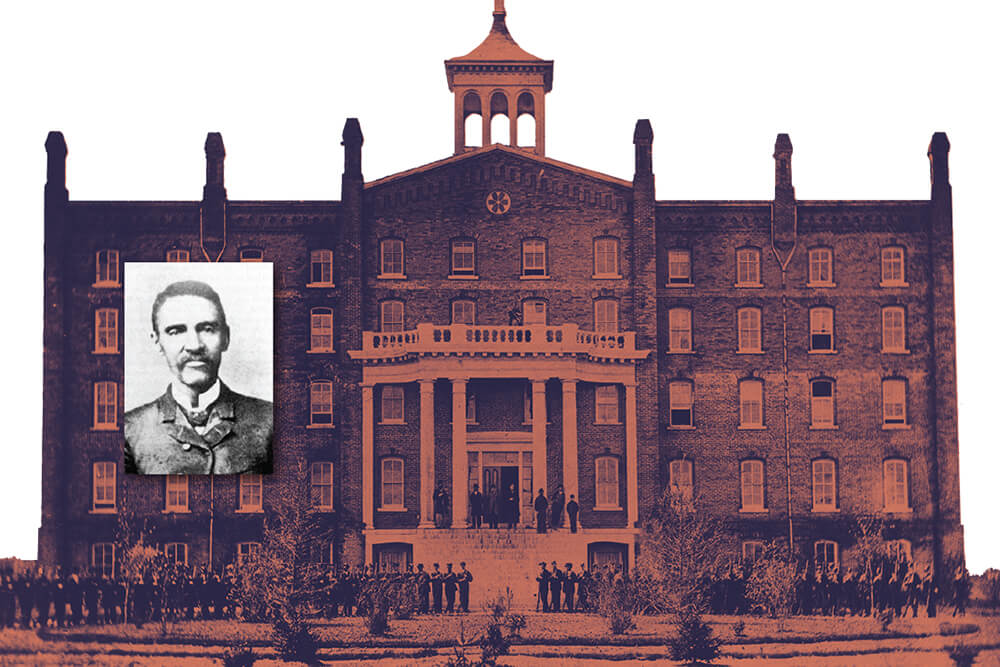

The original University building on opening day, 1868, and John J. Bird (Images courtesy of UI Archives)

On March 2, 1868, the Illinois Industrial University—later known as the University of Illinois—welcomed its first students. There were 50 of them: all young, all male and all white. Two years later, the school would admit its first women. There were 15 of them, and they, too, were all white. The year after that the first international student arrived. He also was white.

Black history at Illinois began in 1873—but not in the way you might think. The first Black person to be affiliated with the University was neither student, faculty nor staff, but rather, a member of the Board of Trustees.

Let that sink in.

His name was John J. Bird. An advocate for African American rights, he became well-known in southern Illinois for helping to elect Black Republicans to local offices, many of which had been historically Democratic. Illinois’ Republican governor, John Beveridge, rewarded Bird by making him a trustee of the new state university.

Illinois would not welcome its first Black student for another 14 years.

The First Black Students

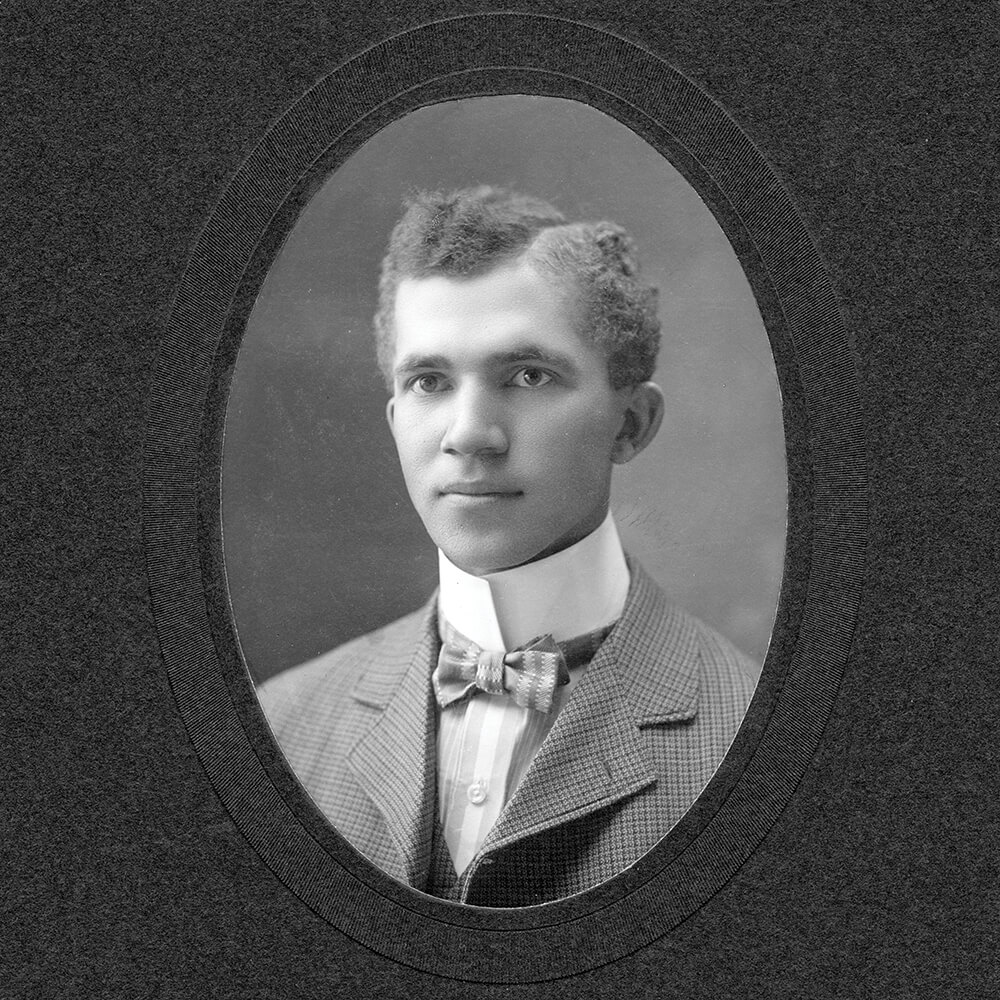

The U of I’s first Black graduate, William Walter Smith, earned two Illinois degrees. (Image courtesy of UI Archives)

The University of Illinois was nearly two decades old when its first Black student enrolled in 1887. He was Jonathan Rogan, of Decatur, and he stayed at Illinois for one year.

The first Black student to graduate from the U of I was a Broadlands native named William Walter Smith, the scion of a prominent, local family. A literature and arts major and editor-in-chief of The Illini newspaper (now The Daily Illini), Smith finished his first Illinois degree in 1900. In 1907, he completed his second Illinois degree, a B.S. in civil engineering. He later worked for the Chicago meatpacker Armour & Co. in Argentina, where he supervised the construction of refrigeration plants and other facilities.

Maudelle Makes the Grade

If you flip through the senior portraits in the 1906 Illio yearbook, you’ll come across one that stands out from the others—a young woman from St. Louis identified as “Mandelle Brown.”

She was the only Black woman on campus: isolated, alone, but determined to make the most of her education, even if theyearbook staff did not spell her name right.

Because her name was not Mandelle. It was Maudelle, with a “u.” And when she became the first Black woman to graduate from Illinois—with high honors, in mathematics—she did so with a dream: to be an astronomer.

But Black women were not allowed to be astronomers.

So she became a math teacher. And 20 years later, when she sat for the Chicago Public Schools’ principals exam, she proved all the people who doubted her wrong by earning one of the highest scores.

Maudelle T. Brown Bousfield, 1906 LAS, became the first Black principal in the CPS’s history.

In 2013, the U of I honored her legacy and achievements by making her the namesake of its newest residence hall. This time, they spelled her name right.

A Guiding Hand

It was 1895, just after New Year’s, and Albert R. Lee was at the U of I to see a man about a job. Black, 20 years old, autodidactic and full of confidence, the Champaign native walked into University President Andrew Draper’s office, “with all the egotism and fearlessness of youth,” and completed the interview without breaking eye contact. Draper hired him on the spot.

So began Albert Lee’s legendary, five-decade career at Illinois.

The second Black employee in University history, Lee quickly proved himself indispensable—supremely competent and suited for any and every task, often far outside his job description. He would grow into a model civil servant, eventually rising to the position of chief clerk and working under seven U of I presidents.

But his greatest contribution to the University was his service to Illinois’ Black students.

During the first half of the 20th century—a time when Black students were not allowed to live in campus housing or to eat in nearby restaurants—Lee was their unwavering advocate. Known as the “unofficial dean of Black students,” Lee used his standing in the local community to help them find work, as well as housing with families in Champaign’s North End neighborhood. Sometimes, he even deferred payment on their tuition and fees so that they could stay in school.

Lee also helped Black students find a sense of community, first by getting them involved with the historically Black Bethel A.M.E. Church and, later, by using his influence to find chapter houses for Illinois’ Black fraternities and sororities.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that the University’s Black students depended on Lee for their survival. He was their patron saint and protector, and he paved the way for generations of Black students to follow.

In 2018, 70 years after his death, the U of I recognized the importance of Lee’s life and work by dedicating a new headstone for his grave in Mt. Hope Cemetery on the south part of campus. The dedication was attended by Lee’s family, his church (which co-sponsored the effort) and members of the University community—among them, a number of current Black students.

Albert Lee would have been delighted.

Breaking Barriers

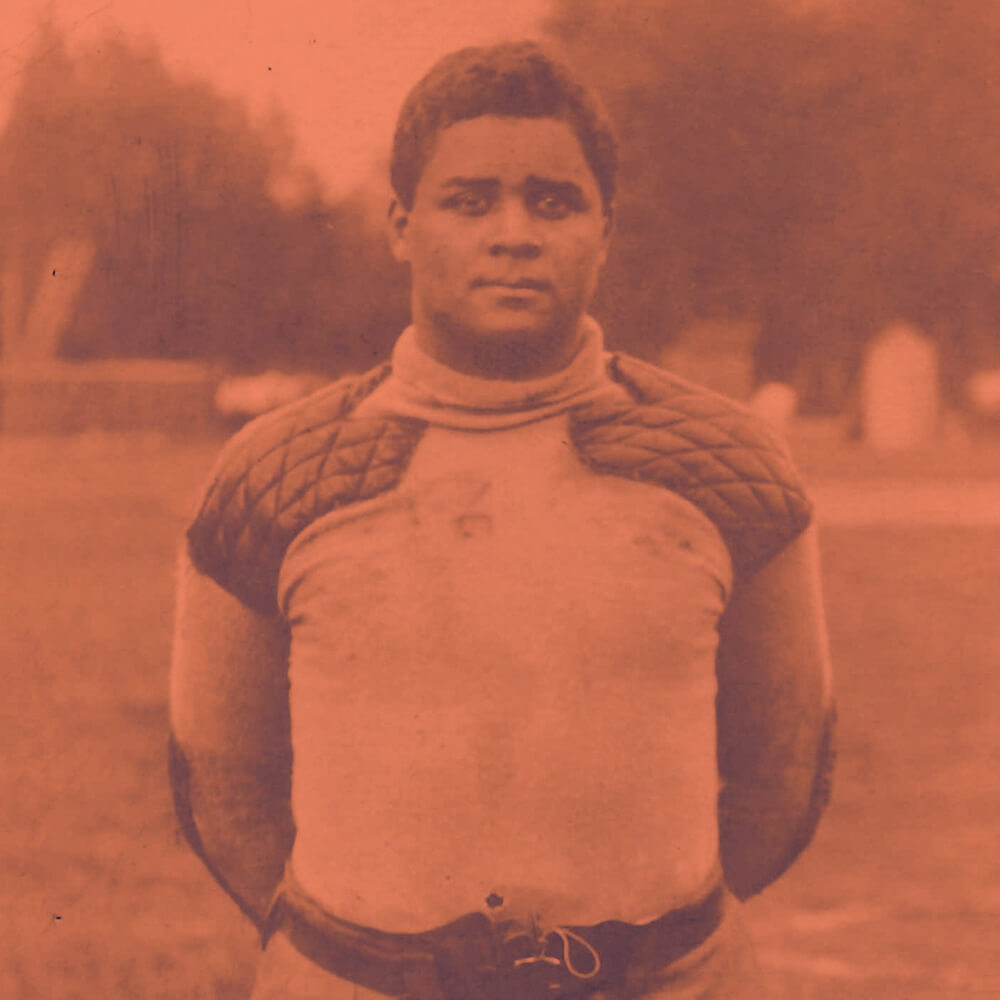

It’s spring 1904. William Walter Smith is in the middle of his second Illinois degree. Maudelle Brown (not yet Bousfield) is a sophomore. Albert Lee is not even a decade into his long career. And on the north part of campus, a young man named Hiram Hannibal Wheeler runs wind sprints at Illinois Field, and quietly enters the history books as the U of I’s first Black student athlete, as a member of the track & field team.

That fall, Wheeler also joins the football team. He and teammate Roy Mercer Young (shown here) become the school’s first Black varsity football players. Young goes on to letter twice.

Neither man will graduate, though Wheeler will go on to work as a clerk in the U of I’s College of Agriculture. Young will finish his education at Northwestern University, becoming a dentist and finding his calling as a minister.

But together, way back in 1904, they set the stage for the thousands of Black student athletes who would follow in their wake.

“Jim Crow Must Go!”

It’s 1945: the war is over, the world has changed, and a measure of progress comes for Black students at the U of I.

In the fall, Quintella King and Ruthe Cash become the first Black students to live in U of I residence halls. Frederick Ford, ’48 BUS, MS ’49 BUS, is elected to the Student Senate. (Three years later, he serves as its president.) And the Student-Community Interracial Committee—a group of faculty, staff, students and locals—forms to fight discrimination by Champaign-Urbana businesses.

Over the next decade, the SCIC and its descendants successfully protest against discrimination in local restaurants, theaters and other establishments, many of which open to Black customers for the first time.

But their work is never done. In 1953, All-American halfback J.C. Caroline is illegally denied a haircut in a campus barbershop because of his race—despite the fact that his photo is on display in the shop’s front window. A series of protests end such outright discrimination by local businesses.

Yet no amount of protests can stop business owners from making Black students feel unwelcome.

Greek Life

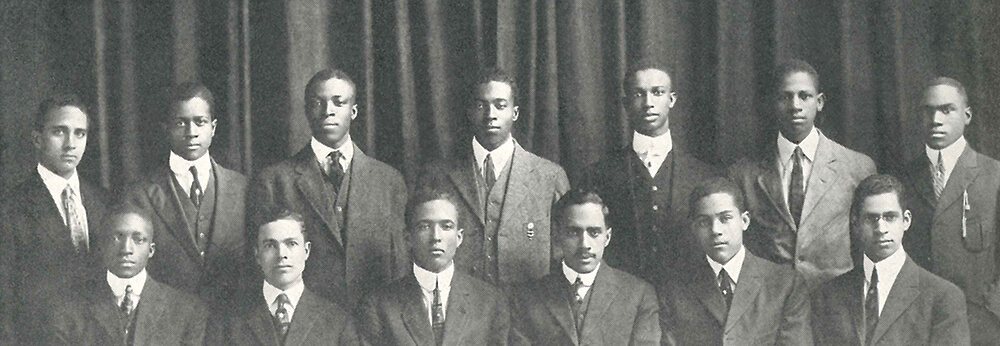

On a cold February day in 1913, a fellowship of nine young Black men met for dinner at Wheeler’s Cafe in Urbana—the only restaurant that would serve them. All were students at the U of I and, collectively, they were the original members of Kappa Alpha Nu Fraternity, Inc. (Two years later, the organization became Kappa Alpha Psi.) That dinner was their founding banquet and the beginning of Black Greek life at Illinois.

In time, the campus would have nine Black Greek Letter Organizations, including Alpha Kappa Alpha, Gamma Chapter, the first Black sorority.* Each provided housing and a sense of community for its members, who were not permitted to live in University housing and often faced open discrimination by local businesses and in the classroom.

Those organizations “were our salvation,” recalled Lorenzo Martin, ’57 LAS, in 2002. “We all had a bond because we went through so much hell just to exist,” he said. “The fraternities and sororities kept us sane.”

Today, more than 100 years after that dinner at Wheeler’s Cafe, the Black Greek community remains a salvation for its members—each chapter house a safe and inclusive place where Black students help each other survive and thrive at the U of I.

*The “Divine Nine” are Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc., Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc., Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc., Iota Phi Theta Fraternity, Inc., Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity, Inc., Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc., Sigma Gamma Rho Sorority, Inc. and Zeta Phi Beta Sorority, Inc.

Fifties Black Illini

Clarice Davis Presnell, U of I’s first Black Homecoming Queen, in 1951 (Image courtesy of the Chicago Defender)

The 1950s: It was a decade that saw the first Black Homecoming Queen in the Big Ten, Illinois’ Clarice Davis Presnell, ’52 LAS; the first Black players to start on the men’s basketball team, Mannie Jackson, ’60 AHS, HON ’08, and Govoner Vaughn, ’60 AHS; and an annual series of events, “Negro History Week,” that attracted students of all races.

Nevertheless, the U of I remained a largely inhospitable place for Black students. Fewer than 200 attended the University, and in their small number, they found a home on campus through their relationships with each other: hanging out at the Illini Union, holding Black all-Greek picnics and becoming part of the local Black community.

In the 1970s, those alumni began to organize reunions, and they gave themselves a nickname: the Fifties Black Illini, or “FBI.”

FBI reunions became cherished events where alumni could reminisce about their experiences, mentor each other’s children and grandchildren, and walk the campus that brought them together in the face of adversity.

Say It Loud, say it Proud

Three dozen students, half of them with Afros, many wearing dark jackets and combat boots, stand outside the English Building offices of Chancellor Jack Peltason. They are the Black Student Association, and they come with a list of demands.

Founded by students and community activists in 1967, the BSA was an advocacy group that frequently protested at the offices of administrators and eventually met privately with the chancellor to discuss their concerns: equity in education, increased Black enrollment, the end of discriminatory policies and an improved learning experience.

The BSA would serve as a major advocate for Black students throughout the late ’60s and ’70s, by helping to promote and preserve Black student experiences through publications such as Drums, The Black Rap and Irepodun (the Black alternative to the Illio yearbook), organizing arts weekends that celebrated Black creativity and hosting lectures by prominent Black thinkers, such as Bobby Rush and Fred Hampton.

But the quality of Black student life at that time was tenuous at best, and the BSA regularly protested against the treatment of Black students and what they saw as the administration’s token efforts to practice affirmative action.

Representation Matters

February 1960: Four young Black men sit at the “whites only” lunch counter at a Woolworth’s department store in Greensboro, N.C.

In the years that follow, the Civil Rights Movement will emerge as a clarion call for U of I students of all races (though there remain many who are opposed to racial equality).

On campus, students continue the anti-discrimination protests of previous decades and respond to national events by taking action. (For example, in 1963 they host candlelight vigils for the victims of the infamous Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, Ala., inspiring like-minded vigils at more than 400 schools across the nation.)

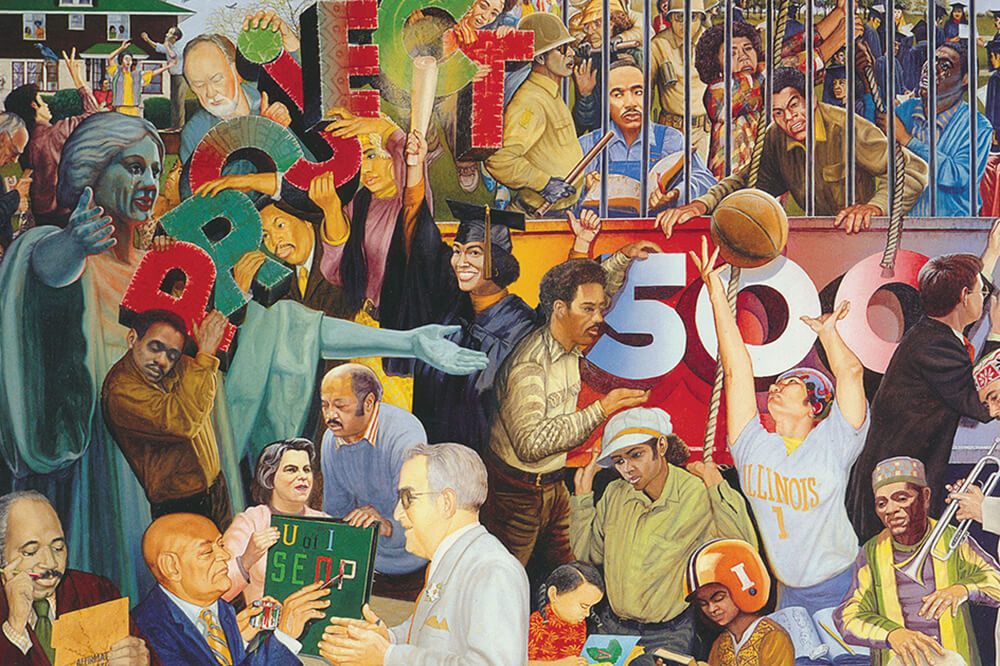

University administrators also respond to the demands of the movement, devising plans to create equal educational opportunities for “underrepresented” students and especially Black students, who comprise only 1 percent of Illinois’ enrollment.

Following the April 4, 1968, assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and spurred by student activism, the U of I

feels an increased urgency to admit more Black freshmen.

Less than a month after King’s death, Chancellor Jack Peltason announces the Special Educational Opportunities Program, an effort to increase Black enrollment. Ultimately, the program becomes better known by its nickname: Project 500.

Under the leadership of Dean Clarence Shelley, the program admits 583 students that fall, tripling the number of Black students on campus.

However, the growing pains, resulting from both systemic racism and the aggressive timeline, are immediate.

On Sept. 9–10, more than 200 students hold a sit-in at the Illini Union over housing and financial aid discrimination related to Project 500. Protestors argue that the program’s organizers did not provide enough housing or sufficient financial-aid packages to cover the cost of attendance. The University’s Black students demand better. Unfortunately, someone calls the police, leading to the arrest of all 244 protestors. It is the largest arrest of Black students in U.S. history and is widely criticized as a racially motivated miscarriage of justice.

Today, it remains one of the most shameful episodes in U of I history.

BNAACC

The Bruce D. Nesbitt African American Cultural Center, past and present. Its new building, opened in 2019, was designed by Dina Griffin, ’86 FAA. (Images courtesy of UI Public Affairs)

Feb. 9, 1969: The Black Student Association is once again in front of Chancellor Jack Peltason’s office, with a list of 41 demands designed to improve the lives of Black students. Chief among them is the creation of a Black Cultural Center, echoing a request made by Dean Clarence Shelley several months earlier.

A week later, 125 white students protest outside the Chancellor’s office in favor of the BSA’s demands. Dean Shelley repeats his request to the chancellor for a cultural center.

In the Fall of 1969, the Afro-American Cultural Program opens in an American Four-Square house at 1003 West Nevada Street. Students affectionately call it “The Black House.”

It quickly becomes the hub of Black student life, helping Project 500 students adapt to life on campus. However, its early years are fraught with problems, including a lack of institutional support and broken promises by campus administrators, which lead to a revolving door of Black House directors, one after another resigning in frustration.

Finally, the program finds stability in 1974, when it moves into a larger house at the corner of Mathews and Nevada, and Bruce D. Nesbitt becomes its director.

Over the next 22 years, Nesbitt transforms the Afro- American Cultural Program into a bustling and beloved force on campus. Despite operating on a small budget and with a small staff, under his leadership the Black House expands its programming and services, launching such long-running initiatives as the Moms Day Fashion Show, Theatre of the Black Experience course, OMNIMOV Dance Troupe, The Griot newsletter and Black History Month programs for local schools.

In 2004, the Black House is formally renamed the Bruce D. Nesbitt African American Cultural Center, in honor of its longest-serving director. Forever after, students know it as BNAACC (pronounced “bee-knack”).

Today, from its new, modern headquarters (on the site of its former home), BNAACC continues to celebrate African American culture and to provide a campus sanctuary for Black students, keeping Nesbitt’s legacy alive through new initiatives such as the 100 Strong learning and community-building program and the Shelley Ambassadors, an effort to recruit more Black high school students to the U of I.

Stand Up and Sing!

In 1968, with the chaos of Project 500 affecting the lives of many Black students, four freshmen—Carol Pearson, ’73 AHS; Vickie Bastic; Roy Haynes, ’73 AHS; and Albert Moore—found a singing group as a way to bring people together. They call it the Black Chorus.

The chorus holds its first concert on May 26, 1969, in the West Lounge of the Florida Avenue Residence Halls, and it never looks back. That same year, the Afro-American Cultural Program and the U of I School of Music become its co-sponsors, and it slowly grows into a beloved ensemble that regularly performs on campus, casting a spell on audiences with its signature mix of jazz, blues, gospel, spirituals and soul.

In 1981, the Black Chorus strikes gold when Ollie Watts Davis, MMUS ’82, AMUSD ’88, becomes its director. Over her long tenure, Dr. Davis develops the chorus into one of the treasures of the University, a symbol of Black excellence and cultural celebration whose renown grows with each passing year.

A More Perfect Union

Mariama. Ebony Umoja. Ewezo. These are only a few of the beautifully and symbolically named organizations that help Black students adjust to life in U of I residence halls.

Known as Black Student Unions, they’ve been a saving grace for thousands of residents and a vehicle for social change for thousands more during the past five decades.

Overseen by the Central Black Student Union, the BSUs fulfill many of the same functions as the old Black Student Association of the 1960s and ’70s. They organize conferences that explore the challenges of the Black student experience; hold special events, like the Black Dad’s Day program; and protest injustice on campus and in the world at large, such as the 2014 killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo.

No matter what they do, the BSUs are united by the spirit of Salango—Pennsylvania Avenue Residence Halls’ organization—which means: We come together to create something beautiful out of love.

Getting Creative

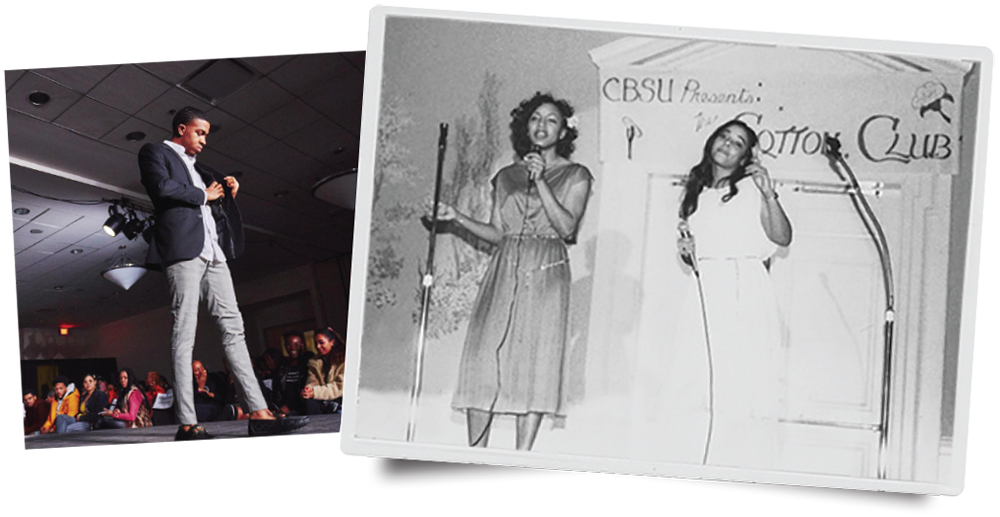

Fresh, dressed like a million bucks, students walk down the runway (but not in all-blue Chucks). Dresses, suits, boat shoes and scarves are a few of the items on display as the audience, from ringside seats, watches their friends play model for the day.

This is the Cotton Club Fashion Show, a long-running, annual tradition for the University’s Black students. First organized in 1981, the Cotton Club was originally created to showcase Black students’ talents in the arts. Forty years later, it is a weeklong celebration sponsored by the Central Black Student Union, with events all over campus, including gospel, rap and Motown concerts, a Soul Train Karaoke Night, a variety show and, of course, the fashion show.

The Cotton Club is an enduring example of the many ways in which Black student groups have used creativity, art and performance to celebrate who they are and where they come from.

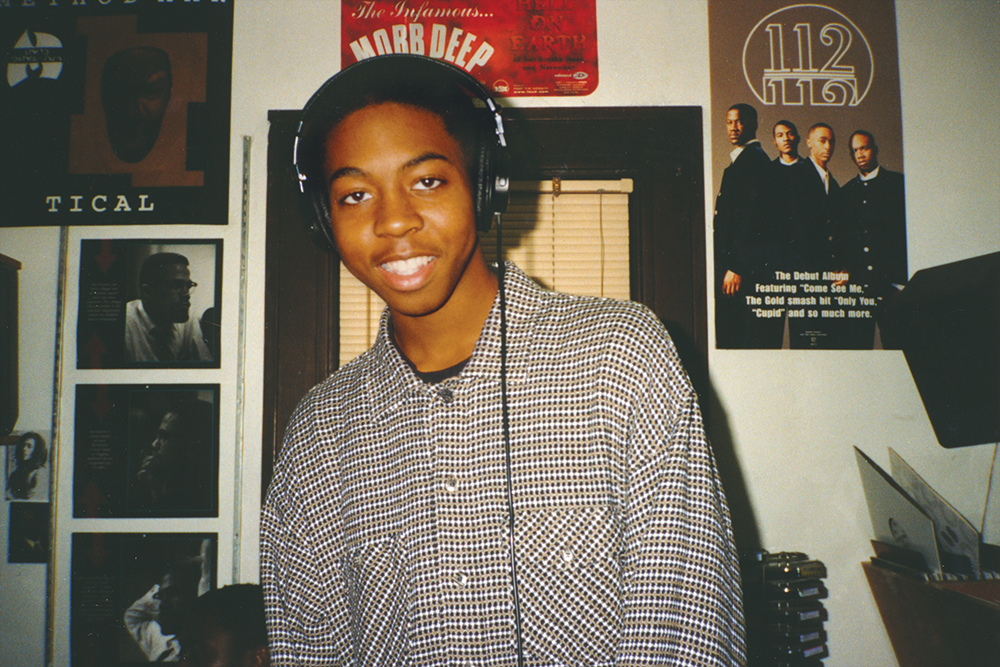

Where Black Music Lives

In 1982, controversy struck when the campus radio station WPGU decided to cancel its soul music programming, leaving students with no Black music programming of any kind. In response, students from BNAACC founded their own radio station: WBML, “Where Black Music Lives.”

It was the first Black music station in Champaign-Urbana.

Over the next four decades, it would become a training ground and creative outlet for students and a beacon of the Black community.

After a period of inactivity, last year BNAACC re-launched WBML for the newest generation of students, with a 21st-century tag-line: “Where Black Media Lives.”

Today, WBML is a place where you’re just as likely to hear a talk show about the Black diaspora as you are to hear music—it’s a station that makes you think as often as it makes you dance.

Black Empowerment

Since the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, one of the hallmarks of the Black student experience has been the celebration of Black empowerment.

Students explore their heritage and identities by getting involved in community events. These include the annual Martin Luther King Jr. Symposium, which honors Dr. King’s legacy and recognizes members of the Black community who embody it; conferences that address what it means to be Black in the modern world, such as Men of Impact and Women of Color; and community outreach, such as BNAACC’s Black History Month program for Champaign County schools, which was initiated in 1988.

On campus, students put their own spin on empowerment by creating lasting traditions, such as African American Homecoming, which grew out of the step shows that Black students began organizing in the 1970s. First sponsored by the Illini Union Board in the early ’80s, the tradition has grown to include a dance, pageant, fashion show and step competition over the past 40 years.

Black Congratulatory

Dashawn Julion with his family at the Black Congratulatory ceremony, 2017 (Image courtesy of Illinois Public Media)

You may have been to a Commencement ceremony or two in your day, but unless you’re a Black alum from the U of I (or a friend or family member of a Black alum), there’s a good chance that you’ve never been to a Commencement ceremony like the Black Congratulatory. First organized by the Afro-American Cultural Program in 1978, Black Congratulatory is a one-of-a-kind, annual celebration of Illinois’ newest Black graduates. Friends and family pack into Huff Hall—no tickets necessary, come one, come all—the soundtrack of cheers and whoops preceded not by “Pomp and Circumstance,” but by Donny Hathaway’s “To Be Young, Gifted and Black” and the Negro National Anthem.

For more than 40 years, the Black Congratulatory has been a cherished event for students and their families—an unpredictable and moving sendoff, made memorable by sorority sisters’ choreographed dances across the graduation stage and speeches by students that acknowledge the shared struggles they have experienced along the way.

Reunited

Oct. 10, 1980: Cecil Bridgewater is onstage at the Krannert Center for the Performing Arts, trumpeting up a storm, while his brother Ron matches him note for note on his sax, and the band falls in behind.

It’s another spectacular night at KCPA. But it’s also so much more.

Because when the Bridgewater brothers look out into the crowd, into the concert hall that’s almost always predominantly white, they see almost nothing but Black faces: 400 Black alumni, with their families in tow.

It is the first meeting of the University of Illinois Black Alumni Association.

Over the next two decades, the UIBAA becomes an essential part of the Black Illini experience—hosting reunions and networking events, and creating a scholarship fund for incoming freshmen.

In 2002, Alicia Gilmore Catching, ’89 LAS, EDM ’02, and Kevin McFall, ’89 LAS, restructure the UIBAA as the Black Alumni Network, guaranteeing its survival long into the 21st century.

“We Demand Better”

In the decades following the tumultuous 1960s and ’70s, Black students on campus continued to protest against social and racial injustices. And not only about local issues that affected them directly. Whether it was the murders of Black youths in Atlanta or the system of apartheid in South Africa, they were on the street, signs in hand, making themselves seen and heard.

Since the 2010s, Black Lives Matter protests have been a common sight on campus. First sparked by the 2014 killing of Michael Brown by police in Ferguson, Mo., BLM became a rallying cry for Black students and their allies, with demonstrations taking over the Main Quad, Green Street and other locations, often led by student organizations and Greek letter chapters, including Alpha Kappa Alpha.

Despite this activism for equity and justice, today’s Black students still experience personal and systemic racism as they try to earn their degrees. Yet they persist, in a quest for meaningful and lasting change.

Inspired by the students that came before them, in 2017 a group called the Black United Front advocated for a 21st-century version of Project 500—“Project 1000”—that would provide better educational opportunities for future generations of underrepresented students.

The group staged protests around campus and even interrupted a Board of Trustees meeting to make sure their voices were heard.

“We don’t have the resources that other students on this campus have,” said BUF member Shontierra Anderson, ’19 LAS, at the time. “There are luxuries that other students have that Black students don’t, and there’s support that we lack, and advisement that we don’t get,” despite being 5.3 percent of the student body.

The Black United Front spoke and the University eventually listened.

In 2022, the U of I announced the Access 2030 initiative, an effort to increase the number of graduates from underrepresented backgrounds by 50 percent by the end of this decade.

The Chancellor Jones Era

A man with a plan and a radiant smile, and an orange necktie he was born to wear.

In 2016, a new era dawned at Illinois, when the University hired Robert J. Jones as chancellor. An eminent crop physiologist and former president

of SUNY Albany, Dr. Jones became the first African American to serve as the campus’ top

administrator.

Seven years later, he has already earned his place as one of Illinois’ most impactful chancellors, not only through his leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic—which established the U of I as a standard-bearer for testing and accountability—but also for his tireless efforts to make the campus a more diverse and inclusive space for underrepresented students.

Among his many successes on that front, Chancellor Jones revamped the University’s Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion and hired its first vice chancellor, Sean Garrick, who is Black; created an open dialogue with Illinois’ Black students about their campus experiences; and made new investments in scholarship related to systemic racism and social justice.

The spirit of increased diversity and representation that Chancellor Jones has brought to Illinois is evident all over campus. In the past year alone, the University has installed a portrait of Albert Lee in the Student Dining and Residential Programs Building; hosted “Black on Black on Black on Black,” an immersive faculty exhibition at Krannert Art Museum that explores Black identity, trauma, healing and education; and dedicated a new monument outside BNAACC to celebrate the legacy of Project 500.