Their Stories

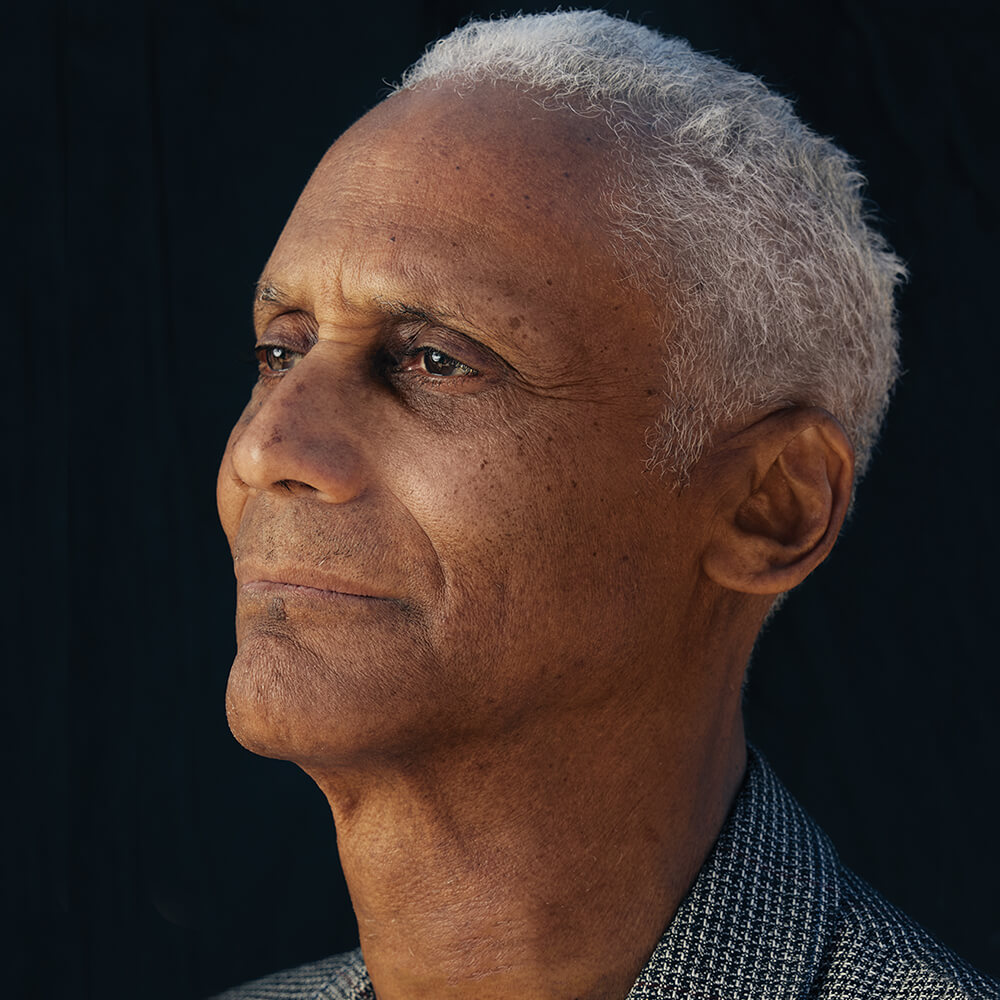

Damon S. Williams, ’78 ENG

The Managing Member of DSW Water Strategies hails an Illinois engineering professor who “took a chance on me” and now pays it forward with an Illinois scholarship for future Black engineers

As told to John W. Fountain

I showed up at Champaign-Urbana at the Civil Engin-eering Dept. and basically presented myself to a gentleman named [Professor] Richard S. Engelbrecht. He took a liking to me. He took a chance on me. He was in my corner.

Maybe it was my unusual approach—sort of like walking into a company and asking for a job interview without having applied. I guess I presented myself in a way that he took a liking to. We never talked about it.

I’m originally from Brooklyn, N.Y. In high school, I wanted to go someplace where I could pursue a degree in chemistry because I wanted to be a research chemist. I ended up at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago. But it didn’t take very long for me to realize that I wasn’t likely to become a research chemist because I didn’t like the chemistry lab.

“People were interested not only in my success, but also how I was feeling. They had a sense of humor. It makes all the difference in the world.”

I changed my major to physics and got my physics degree from Roosevelt University in Chicago. I then became involved in a religious group that was building a community southwest of Kankakee, Ill. I also got involved in a lot of that community’s civil engineering work, designing and building roads and drainage systems. I was not an engineer—we were doing it by the seat of our pants. We designed and built our own drinking-water and wastewater treatment facilities, and I ultimately ended up operating both of them. When I decided to leave the group, I thought, “Well, what do I do with the rest of my life, my career?”

I decided to pursue engineering at Illinois. I chose the

U of I because it was close and a major university.

Little did I know that it had one of the best civil engineering schools in the nation. And Professor Engelbrecht [who died Sept. 1, 1996] found some scholarship money for me.

Later, I realized that I had had a sense that the professors at IIT were kind of on a pedestal, which created a certain amount of standoffishness, aloofness. I never really felt that I could have a personal relationship with those professors. When I went to Illinois, it was totally different. People were interested not only in my success, but also in how I was feeling. They had a sense of humor. That makes all the difference in the world. I still have many of the relationships I developed at Illinois.

When I graduated, I made a commitment to help other engineers continue their education in civil engineering, particularly water engineering. So, I started putting money into a fund at Illinois. Over the years, it’s grown considerably. In fact, we’ve had a dozen individuals, all African American, receive the Damon S. Williams Scholarship [established in March 1998].

That’s actually the thing I’m most proud of about being a part of the University of Illinois: the establishment of this scholarship that will continue well into the future. I want to dance out of this life feeling that I’ve done something that impacts people in a positive way.

Cheryl W. Thompson, ’82 LAS, MS ’84 MEDIA

The Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and NPR investigative reporter on the importance of support and giving back

As told to Monica Fountain

There were three of us. I was the youngest. My parents said, “You can go to any school in the state of Illinois. That’s what we can afford. A state school.” We were all in college at the same time. I chose Illinois because I thought it was a really good school, and my brothers were there.

After I completed my undergraduate degree, I applied to graduate school at Illinois. Tom Littlewood was director of the journalism school then. I remember getting a letter from him saying, “We would love to have you, but we don’t have enough seats.” I wrote back to him and said, “That’s OK. I’ll bring my own chair.” That’s how I got into the journalism program.

The person who was my savior and guardian angel was Professor Robert [Bob] Reid. He was a print guy, but he liked me. I think he saw potential in me. I adored him, but he was tough. I remember a paper for which he had originally given me an A-minus. He scratched out that grade and changed it to a B-plus because I had a comma in the wrong place. I never forgot it, and to this day, I check every comma before sending in my copy. He was by far my favorite professor.

“Thank goodness for [Dean] Michael Jeffries and his Council for Opportunity in Education program, because that’s where I and other Blacks could go for help.”

I had an advisor. He could not have cared less about me. I was just a Social Security number. As a freshman, you need that guidance, or at least I did. The person who kept me sane was Dean Michael Jeffries. He was the kind of person you could go to, and he would always listen. He never judged. Thank goodness for Michael Jeffries and his Council for Opportunity in Education program, because that’s where I and other Blacks could go for help. I don’t know one Black student who knew Dean Jeffries who didn’t think the world of him.

There weren’t a lot of Black students in our classes. That’s why I was so social. That allowed me to get to know a lot of Black students on campus. I was the editor of The Griot. I was in Black Chorus and an Alpha Angel. I pledged Alpha Kappa Alpha.

My aunt was an AKA who pledged in 1932 at the U of I. She’s the reason I became an AKA. She hated the U of I because she had professors who would sit her in the front of the class and tell “Black jokes.” She said, “I will never set foot on that campus again.” But she would—three times, to see each of us graduate. All three of us got our undergraduate and graduate degrees from Illinois.

I had a good experience because there were people at Illinois who really cared about me. That made a huge difference. I vowed that if I were ever in a position to help young people who looked like me, I had to do it. I had a lot of people who lifted me up along the way.

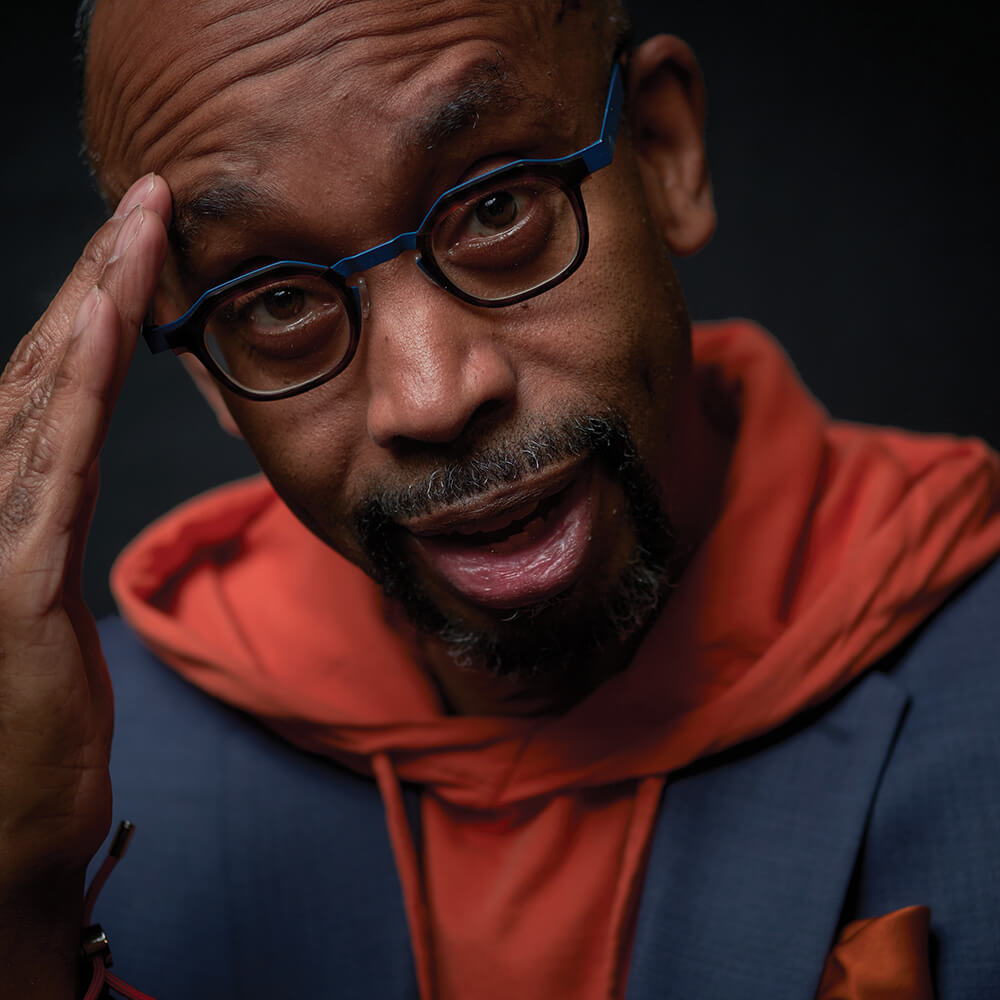

Kevin McFall, ’89 LAS

The digital transformation strategist for media and cloud-based tech companies credits learning to find his “tribes” at Illinois as key to his success, both then and now

As told to John W. Fountain

The University of Illinois grabbed me. I’m not exactly sure what it was. It is hard to put a finger on it. But I bleed Orange and Blue. I arrived in August 1981, having spent two weeks on campus in 1980 as part of a summer program called Minority Introduction to Engineering. That program probably cemented my desire to attend Illinois.

At its core, the program was another rung in my own coming-of-age story, of self-esteem building, of feeling some sense of independence and accomplishment outside of my parent’s home on the South Side of Chicago—my mother, an educator; my father, a scientist. But the core experience was one of building camaraderie, of literally walking into the buildings on campus and taking my seat. It really resonated.

I suspect that feeling could have occurred at other institutions. But there was something about the Urbana-Champaign campus that really grabbed ahold of me.

This occurred despite having landed in east-central Illinois on a quintessential Midwestern college campus surrounded by “sundown towns.” Central Illinois was absolutely part of that same phenomenon that was occurring in the South and other places.

“I came to realize, despite what I may have experienced, that I have full ownership and a seat at the table of that experience. And since I came to that reconciliation of sorts, that is the sentiment I maintain: I bleed Orange and Blue. And it is just as much my University as it is anyone else’s.”

Throughout my life, it has been all about finding my “tribes.” That was probably accelerated—or exacerbated—at Illinois. The Association of Minority Students in Engineering was one of those key tribes that helped me feel like I belonged. It provided a pathway toward what I’ve ultimately come to describe as the embodiment of the U of I experience—learning how to be resourceful. In my less mature days, I saw it as learning how to survive.

I formed one of my other tribes on my own. It was a collective of campus deejays who called themselves BMG or Better Music Group. Anytime freshmen would come to campus and had deejay talent and skills, I pounced on them, recruiting them to join. I also was part of a team that protested and demanded that WPGU radio station reinstate the Black programming slot on Sundays. The station’s management ultimately gave back some time to us on WPGU, and we got WBML established [a Black cable radio station housed at the African American Cultural Center].

Many Black students had challenging experiences—from being called the N-word or being dismissed by instructors and professors to being left out of resource pools like study guides and old exams or knowing the right instructor from whom to take a class. All of those things resulted in Black students not having a great taste about their U of I experience.

Whether they finished at Illinois or left and went somewhere else to finish, they didn’t want any part of the University anymore. There were a large number of Black students for whom that was the case. There were some who felt they just never belonged.

For those of us who made it through and claimed ownership, there was a realization that “I can’t do this alone. I have to rely on my community to achieve what I set out to achieve here.”

I came to realize, despite what I may have experienced, that I have full ownership and a seat at the table of that experience. And since I came to that reconciliation of sorts, that is the sentiment I maintain: I bleed Orange and Blue. And it is just as much my University as it is anyone else’s.

My message to future Illinois students of color: Don’t limit yourself. Seek out your community. Seek out your tribe. Seek an understanding of the value you bring to your community and what it provides to you. Then use that as a superpower to engage in the broader community.

Kimi Brown Ellen, ’92 BUS

The co-founding partner of Benford Brown & Associates, the largest Black woman-owned accounting firm in the U.S., on micro-aggressions and finding community

As told to Monica Fountain

At the age of 10, I knew I wanted to be an accountant. I’ve always liked numbers and was good with them. My mother was a beautician. One day, one of her clients came into her shop with a paper ledger that had all of these numbers. I was so excited. I asked her what she was doing, and she said, “I’m an accountant.” I said, “I’m going to be an accountant.” She told me, “You should be a CPA like my boss because he makes all the money.” So I said, “I’m going to be a CPA.”

I chose the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign because at the time it was, and still is, the No. 1 accounting school in the country. It was a natural fit. And my father bribed me. He said if I stayed close to home [the South Side of Chicago], he would make it worth my while. So I turned down Princeton and came to Illinois.

I was often the only Black student in my classes. It was lonely. I remember one time we had a group project, and I did it by myself because no one let me into their group. Now we have a term for what that was: micro-aggression.

“I was often the only Black student in my classes. It was lonely. I remember one time we had a group project, and I did it by myself because no one let me into their group.”

One of my favorite things about Illinois was the community I experienced. At the time, we had about 2,000 Black people on campus, so there was a very strong sense of community. Together, we were our own small HBCU [historically Black college or university]. We would go to the Union parties, hang out at the cultural center. It was around that time when we were all becoming more “woke.” This was during the time of Rodney King. We started doing sit-ins. We sat on [President Stanley O.] Ikenberry’s lawn. On Thursdays, it was The Cosby Show and A Different World night. We would eat dinner together and then watch the programs in somebody’s dorm lounge.

After graduation, I went right into public accounting at Deloitte. On my first day, half of the room was U of I graduates, so I knew everybody. There was one Black girl from an HBCU—Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University. Her name was Alyssia Benford, and we became really good friends. Within two years, we had started our own accounting firm. I was working full-time during the day, and then I would come home and do accounting or taxes for my clients. Accounting is very male-dominated. When we started our firm, I said, “We’re going to use our maiden names because I want people to think we’re men.” [Editor’s note: Kimi’s and Alyssia’s married surnames were Ellen and Lee, respectively.]

The education I received at Illinois made it possible for me to pass the CPA exam. We were totally prepared for that exam. I appreciate the education I received. I also appreciate the community, because if it wasn’t for that, being in those classes and being the only Black person would have been unbearable. Both of my children were accepted to Illinois but I refused to send them. I wanted to send them where they would be celebrated and not just tolerated. There are not as many Black students attending Illinois as there were when I was there, and there’s not the same sense of community. I sent both to HBCUs because I wanted them to have that strong sense of community and family.

Wilbur C. Milhouse III, ’94 ENG, MS ’95 ENG

Once a struggling married college student, the chairman and CEO of Milhouse Engineering & Construction savors the lessons in life, survival and success he learned at Illinois

As told to John W. Fountain

I grew up on Chicago’s South Side. Back then, I wasn’t a very good student. My mom worked two jobs and was not there a whole lot, so I didn’t have a great support system for an education. My mother decided we should get out of the city. So we moved to Park Forest South, Ill., now University Park. I went to Crete-Monee High School, which was mostly white then. The Chicago Public Schools system was closed because of a teacher’s strike, so we couldn’t access my records. Consequently, Crete-Monee put me in classes that weren’t too full, mostly honors courses. I thought, “Man, I’ve got a big secret here; they don’t even know.” I worked my tail off. I’d always wanted to be a good student.

I’m in the classes and doing very well. Then around Thanksgiving, CPS sent my grades. The Crete-Monee administrators were like, “Hey, pump the brakes! This kid’s in over his head. We’re going to have to move him.” Ms. Hood, my math teacher, was a Jewish lady, about 4 feet 10 inches tall, with a little puffy gray afro. She said, “If you move him out of my class, I’m going to quit today.” From that moment, I went from being the below-average student to being the smart student and from being a kid who had promise in math—which my teacher saw—to being able to qualify to get into the University of Illinois.

“In my company, one of our core values is diversity. My experiences at Illinois made me want to have a diverse atmosphere similar to what I had experienced there.”

I get to the U of I, I’m on campus, I love it. I’m a first-generation student going off to a four-year school. I don’t know anything about sororities or fraternities or dormitories, nothing. I’m learning all of this stuff. Then, on Oct. 10 [1987], I had an awful car accident and almost lost my hand. You start to hone in on what’s important.

Then, after all the challenges I had created from having this bad car accident, I decided to get married my freshman year, second semester. My fiancée already had a daughter. Instantly, I’m a father. We’re working. We’re figuring it out. Poor as all get-out. I’m fighting to get into the College of Engineering. I’m fighting to keep us afloat. From working as a night stock clerk at Jerry’s IGA in Urbana to delivering pizza to studying, I just kept on pushing.

A bunch of folks did some amazing things to help me along the way. Dean Paul E. Parker [who died July 2, 2016] saw something in me. I was one of those individuals of whom he said, “I think he has what it takes to make it.” I did well and got my bachelor’s degree, then followed with a master’s degree in structural engineering.

In my company, Milhouse Engineering & Construction, one of our core values is diversity. My experiences at Illinois made me want to have a diverse atmosphere similar to what I had experienced there. Many things—down to the colors of my company, orange and blue—come from various foundational moments that I had at Illinois.

My greatest reward is seeing the growth and the access to opportunity we are able to provide to people. That makes me feel like we’re doing something.

Ruth Tekeste Dicks, ’12 LAS

In her fight for equity, the Teach for America alum and Habitat for Humanity volunteer spent the first part of her career teaching in low-income schools

As told to Monica Fountain

I had a lot of family who went to the U of I and had a great experience there. To be honest, Illinois was not my first choice, but financially it ended up making the most sense for me. I got into all of the schools I applied to, but they were just way too expensive and were not going to give me enough financial aid. The U of I was the cheapest and offered the most scholarship money. It ended up being an amazing choice and the best one for me.

I knew I wanted to major in psychology. I didn’t know what I wanted to do with it, though. I was heavily involved with Habitat for Humanity. I made a lot of trips to build homes in New Orleans, Missouri and Tennessee. I also was very involved with Alpha Phi Omega, a community service fraternity. We did 25 hours of community service per semester and partnered with different community organizations. I did things like tutoring at schools, and volunteering at a horse farm and a senior center.

I took so many cool classes that I didn’t need to take but I was interested in, like the History of Chicago. It was a really incredible class. I learned a lot about Chicago and the messed-up history that is Chicago segregation and racism. I did a research paper for that class about my experience growing up Black in urban Chicago, and it was pretty eye-opening.

“I took so many cool classes…like the History of Chicago…. I wasn’t sure I wanted to be a teacher, but I feel that what I learned in that class led me to become one.”

I wasn’t sure I wanted to be a teacher, but I feel that what I learned in that class led me to become one.

I wanted to help with the injustices in education. At the end of my senior year, I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do, but I knew I wanted to give back. I went to a Teach for America information session, and they got me. It seemed like a really good opportunity to give back and fight educational inequity.

I taught for Teach for America for two years in Miami. I found it very valuable to work with students and see their growth. I really loved working with them. I continued to do that when I came back to Chicago. I taught for about eight years, but eventually, I stopped teaching. I got a little burned out.

I’m in school right now at National Louis University, training in clinical mental-health counseling. I’m interning at a private practice and working full-time as an academic advisor at Loyola University Chicago. Being a teacher in predominantly Black schools, I saw the great need for mental health services and accessibility and the lack of it.

I had a wonderful experience at Illinois. It was an amazing four years. I’m glad I went there.