In Class: Identity Explorer

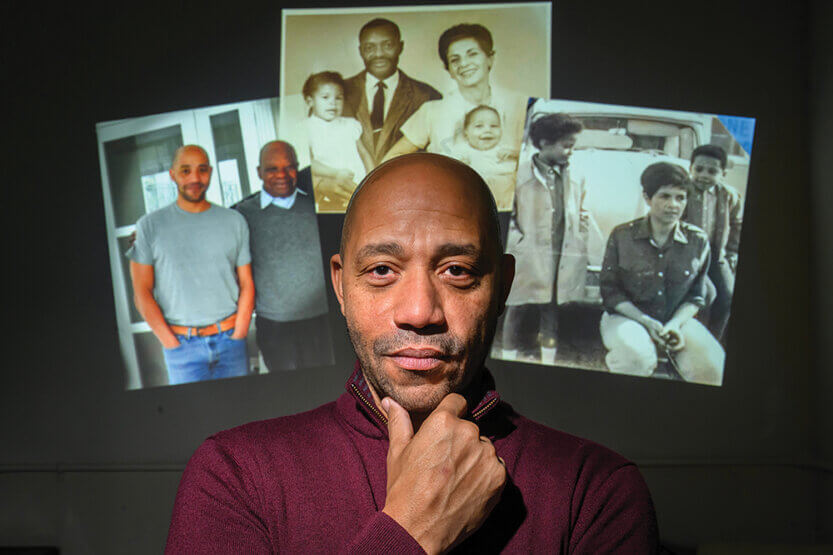

“I’ve been writing since I was 21, 22 years old,” says English professor David Wright Faladé. (Image by Fred Zwicky)

“I’ve been writing since I was 21, 22 years old,” says English professor David Wright Faladé. (Image by Fred Zwicky)

I teach graduate students in our writing program, and I teach literature and cultural studies courses, as well as creative writing, to undergraduates. One of my courses is on slavery and identity. We look at the experience of slavery from various perspectives, with historical documents and literature of the period as well as contemporary material. The literature and cultural studies classes are great vehicles to teach undergraduates how to think critically, to read closely, and to speak and write well.

The world of being a professional writer is so haphazard. I’ve been writing since I was 21, 22 years old, and I’m 69 now. Three-and-a-half decades, and I’ve written three books. Some writers would have that many books in one decade.

My mother was a French Jew who’d survived the Nazi occupation of Paris. She married Jack Wright—a black G.I. and the man I thought was my father—and they moved to the States in the 1950s. I was born in the ’60s and grew up in small-town Texas, a biracial kid. When I was 16, I found out that my biological father was an African who was descended from the slave-trading kings of Dahomey. His name was Max Faladé. He was my mother’s first true love when she was living in France. Long after she had married another man, they briefly revived their affair and produced me.

I met my father for the first time during my junior year in college when I traveled to Ethiopia to visit him. My mom and his sister had orchestrated the meeting. Things didn’t go that well. But he and I eventually got to be friends. He passed in 2018. My mom passed in 2016. I have always been David Wright. Taking his name seemed like honoring both of them.

When I was living abroad, my African grandfather found out about me and wanted to meet me before he died. I got to Benin [Africa] not knowing what to expect. His father was the last king of Dahomey. He took me to the ancestral site where he grew up. There was a family vodun [aka voodoo] altar. All these elderly African people were there. It was a ceremony so that my grandfather could say: “This is our child. He is part of the family.”

I’ve received a fellowship from the University’s Center for Advanced Study to research my family and to write a memoir. Writing memoirs is hard work. But it’s the best way to approach this complicated story.

Edited and condensed from interviews conducted on Aug. 10 and Aug. 28, 2023