Field Guide

As head of exhibitions at Chicago’s Field Museum, Jaap Hoogstraten has revitalized more than 200,000 square feet of permanent installations, ranging from a new Spinosaurus skeleton replica to the Cyrus Tang Hall of China. (Image by Katrina Wittkamp)

It’s showtime for the newest star attraction at Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History: Sobek, a 46-foot-long cast of a Spinosaurus skeleton. This fierce semi-aquatic predator ruled the seas around North Africa 95 million years ago and has won the hearts of dinosaur-obsessed kids everywhere over the past decade, topping T. rex in length and rivaling it in reputation as “alpha dino.”

The press has arrived to chronicle, live, the ascension of this 700-pound, foam-and-fiberglass cast to a swimming position 12 feet above the ticketing area in the museum’s vast Stanley Field Hall. There is a lot riding on this 15-second climb for Jaap Hoogstraten, ’84 LAS, head of exhibitions at the Field Museum.

Hoogstraten plays a pivotal role in coordinating what the museum’s 1.3 million annual visitors see at this world-renowned institution. Sobek—named for an ancient Egyptian crocodile-headed god—will be the only Spinosaurus skeleton on permanent display anywhere outside of Asia. Hoogstraten’s exhibitions team has spent a year planning and collaborating with paleontologists both in-house and in Morocco, artisans in Italy and rigging experts in Chicago to prepare for this momentous installation. “There’s such an incredible feeling of pride and community when you’re working so closely and intensely to make something on this scale happen,” he says.

As cameras roll, Hoogstraten watches anxiously. The skeleton is slowly lifted off the floor, and its weight is transferred to 1/8th-inch-thick galvanized aircraft cables, hung from the ceiling 75 feet overhead. There’s a sharp collective inhale as Sobek bounces a bit upon reaching its resting point. But once it settles into perfect balance, there’s a sigh of relief and a hearty round of applause.

When you work for an institution as historic as the 131-year-old Field Museum, there’s a constant challenge to remain relevant to changing demographics and new generations of museum goers while giving previous visitors a reason to return. That’s where Hoogstraten and his exhibitions team excel. Since 2000, he has been involved in the creation of some 200 exhibitions, many of which were subsequently adapted as traveling shows. He has helped revitalize more than 200,000 square feet of permanent installations, ranging from Sobek to the Cyrus Tang Hall of China.

Such prolific output is possible, in large part, because the Field Museum has always maintained an in-house exhibitions department, a rarity in an industry where outsourcing is the norm. The 60 staff members are as diverse as the exhibitions they create. They come from art schools, trade schools and four-year colleges. Their degrees range from anthropology to acoustics to literature. They’re welders, woodworkers and writers, mold makers, mount makers and digital designers. Their wide-ranging talents drive the department’s long-standing reputation for mastery and innovation. “It really takes a village—a large, crazy and argumentative village—to make an exhibition,” says Janet Hong, ’96 LAS, senior project manager.

Hoogstraten, who studied comparative literature at the U of I, visited many exceptional museums during his globe-trotting upbringing with his Dutch father and Indonesian mother. While attending high school in Cairo, he and a well-connected classmate spent several nights locked in at the Egyptian Museum in the company of King Tut and other royal mummies. He never envisioned that he might one day work in a museum. “I didn’t realize there were jobs in museums for people like me, who weren’t specialists,” he says.

His initial training ground for his work at the Field Museum came, surprisingly, at the farm-to-table Alchemy Cafe in Chicago’s Wicker Park neighborhood, which he owned with his wife, chef Diane Celia Rosen. Hoogstraten had to administer a budget, manage staff, consider group dynamics, gauge customer expectations and reactions, and rotate offerings to keep visitors coming back—all tasks he performs on a significantly larger scale now. “The restaurant set me up for my career at the Field Museum like no other experience,” he says.

He entered the exhibitions field with Ronsley Special Events, where he organized interactive fan experiences for the Super Bowl, Final Four and NBA All-Star Game. Instead of dinosaur bones, his marquee artifacts were jerseys, trophies and the first generation of Air Jordan shoes. “It was exciting work related to what I do now,” he says. “We were engaging with visitors and trying to tell a story.”

When he joined the Field Museum, Hoogstraten says he “felt like it was what I had always been preparing for.” His work has since taken him to many countries and behind the scenes on VIP experiences beyond his dreams. He has surveyed the skyline of Vienna from the roof of its Natural History Museum at midnight. He’s descended into the 7,000-year-old salt mine at Hallstatt, Austria, a site credited with the advancement of civilization in Europe. He’s stood shoulder-to-shoulder in excavation pits with the terra cotta warriors of Xi’an, as he cemented the partnership that brought a contingent of those famous soldiers to the Field Museum for their only North America exhibition of 2016. “Those experiences underscore how lucky I feel to have found this profession,” he says.

With more than 40 million items in the Field Museum’s collections—less than 1 percent of which are on display—possibilities for new exhibitions are limitless. “Jaap is always open and absorbing ideas for different ways we can display the material we have for public learning and enjoyment,” says Deborah Bekken, MS ’89 LAS, PHD ’94 LAS, former director of collections.

Ideas percolate in hallway conversations and at department happy hours. They arrive in proposals from other institutions. They’re suggested by museum members, trustees and the dozens of research scientists on staff. For example, Sobek was proposed by Matteo Fabbri, a postdoctoral researcher on staff. Fabbri was part of the groundbreaking excavation in Morocco in 2014 of the most complete Spinosaurus skeleton in existence (the one scanned for Sobek’s cast) and has since discovered how its dense, penguin-like bones helped it hunt underwater. “Spinosaurus is exciting because it’s evolving science,” Hoogstraten says. “The research is still ongoing.”

Donors are unlikely to contribute money to something that is merely a vague idea. And so every exhibition, from the smallest to the blockbusters, follows an exhaustive five-phase process that requires tremendous collaboration among and across departments. “The joke around the rest of the building is that if you sign up for an exhibitions project, you’re going to be in a lot of weekly meetings,” Bekken says.

While that process is, by necessity, exacting in its details about project costs and revenue, floor and content plans, artifact and interactive element inventories and so on, it’s also intended to foster creativity among Hoogstraten’s team, not stifle it.

“I like the creative freedom that I have on Jaap’s team,” says Latoya Flowers, senior multimedia creative. “I can come to him with the craziest ideas, things that the museum has never done, and he’s open to them.” The intense labor of Flowers and other members of that large, crazy village behind the scenes to transform ideas into reality is nothing less than magical. It’s a complex and mind-blowing blend of art, science and storytelling that can take years to bring to fruition, yet appears so effortless and engaging for visitors of all ages.

While by no means easy, given its size, Sobek was simpler and quicker compared to many other exhibition projects. It took only about a year to complete. There were no priceless artifacts on loan or fragile fossils to safeguard. The main element, the reproduction skeleton, was outsourced to the Italian specialty workshop Prehistoric Minds, which had just completed a similar Spinosaurus model for a Hong Kong museum. Only one touchscreen tablet, called a reading rail, provides context for Sobek to visitors in bite-sized sections of no more than 72 words, per exhibitions department specifications.

SUE—the world’s biggest and best-preserved T. rex—moved from the vast Stanley Field Hall into a smaller, custom-designed gallery. “It works much better because you are confronted by this terrifying animal head-on,” Hoogstraten says.(Image courtesy of The Field Museum of Natural History)

At the opposite end, in terms of complexity, is SUE, the world’s biggest, best-preserved and most complete T. rex. The museum’s top attraction spent its first 18 years in the enormous Stanley Field Hall. “Even though SUE is 40 feet long, in that cavernous space, people were underwhelmed by SUE’s size,” Hoogstraten says.

No longer. “The SUE Experience,” which opened in December 2018, introduces visitors to SUE on the T. rex’s home turf. Additional columns had to be sunk down to the bedrock to support SUE’s weight in its second-floor, 5,100-square-foot multimedia gallery, which transports visitors back 67 million years to a late Cretaceous forest in what became South Dakota. “In a smaller space, it works much better because you are confronted by this terrifying animal head-on,” Hoogstraten says.

Digital animations on multiple nine-foot screens show SUE in action, fighting a triceratops and hunting an Edmontosaurus. Those alone took a year to render with scientific accuracy. Sensing stations let guests experience how SUE sounded, felt and even how its breath smelled. (Answer: terrible.) Flowers, a new team member at that time, created a first-of-its-kind light and video show that’s projected directly onto SUE to point out key details of the reconfigured skeleton. The gallery’s location, within the Griffin Halls of Evolving Planet, places SUE’s chapter in the proper chronological context within the overarching narrative of life on Earth.

“With our exhibitions, we create narratives, much like making a movie or writing a novel,” Hoogstraten says. “As opposed to a science center, where you have individual displays that you read about and then move on to something different, we have a story arc that takes you on an emotional ride throughout the exhibition.”

Such narratives can take a long, long time to develop when you’re dealing with irreplaceable artifacts, large teams and competing institutional priorities. “You develop a slightly different view of time, working in this place,” Hoogstraten says. “Ten years, 15 years can pass. It’s okay, as long as you still see things through.”

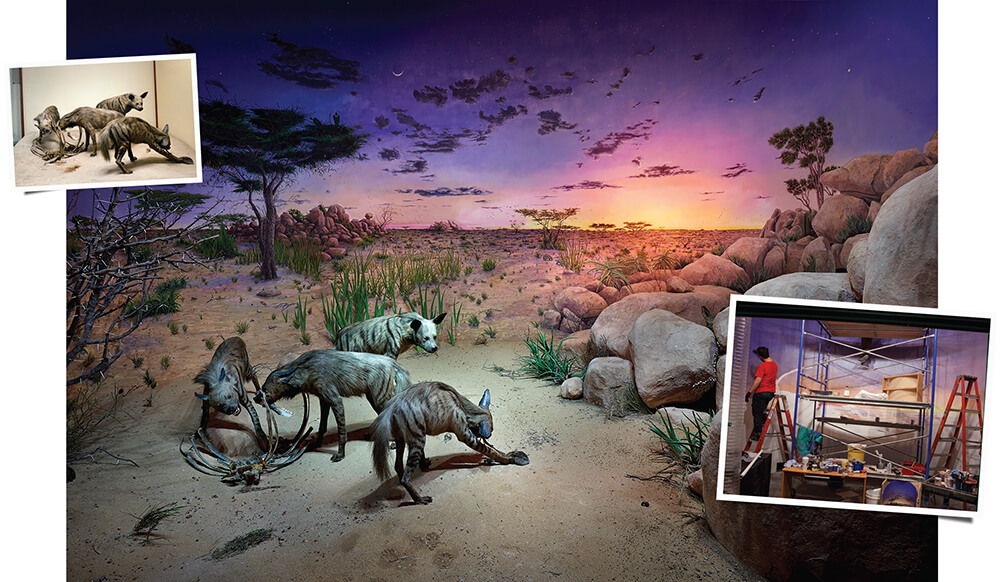

On Hoogstraten’s left forearm is a testament to his patience and perseverance: a tattoo of a striped hyena in the museum. When Hoogstraten joined the museum as operations director in 2000 (he was promoted to director of exhibitions in 2010), a retiring exhibitions staffer named Paul Brunsvold handed over a file on his long-unfulfilled dream project. It would be a new diorama in the Hall of Asian Mammals featuring four striped hyenas mounted in 1899 by Carl Akeley, a legend in the museum world and the father of modern taxidermy. The hyenas had been stuck in a plain glass case in the reptile hall for 30 years. “Paul made me promise to get this done,” Hoogstraten says.

The hyena diorama depicts the African locale where the animals were found in 1896. “There’s talk about dioramas being outdated,” Hoogstraten says. “That’s not true. They really connect with the audience.” (Images courtesy of The Field Museum of Natural History)

While ideas are limitless, budgets are not. The file languished on Hoogstraten’s desk for years. In 2015, the host of The Brain Scoop, the museum’s YouTube channel, asked Hoogstraten if there was an exhibition he’d always wanted to do. Cue the hyena diorama.

“There’s a lot of talk about dioramas being outdated,” he says. “That’s not true. They really connect with the audience. We know that kids relate to these animals, in some ways, better than at the zoo, because they can see them up close.”

The Brain Scoop launched a crowdfunding campaign that raised more than $155,000 from more than 1,500 donors in just six weeks. The finished habitat diorama—the first new one in 60 years—showcases the exceptional talents of the exhibitions department. The mural artist consulted with the Adler Planetarium to portray the pre-dawn sky exactly as it was over that spot in Somaliland (modern-day Somalia) on the day Akeley hunted the hyenas in 1896 for the sake of preserving specimens of an already-shrinking population. The scene’s landscape—aloe plants, dung beetle and bat-eared fox—are all precisely rendered, based on notes and sketches that Akeley made in the field.

When the museum’s tattoo exhibition opened in 2017—complete with an onsite tattoo parlor that sold out its appointments within minutes—Hoogstraten decided that circumstances were ideal for getting the hyena tattoo, his first tattoo, at age 57. “I would never have gotten a tattoo if I hadn’t built the tattoo parlor,” he says with a chuckle.

Hoogstraten has since added others, including cassava leaves, representing his maternal ancestry from Java. Before he retires, he aspires to stage an exhibition highlighting the museum’s Javanese artifacts, which were among the tens of thousands of items preserved from the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago that formed the museum’s founding collection.

Of course, much has changed since the Field Museum was established in 1893, from the processes and materials used to preserve artifacts to the technological leaps that have made immersive multimedia projections and reading rails staples of exhibitions.

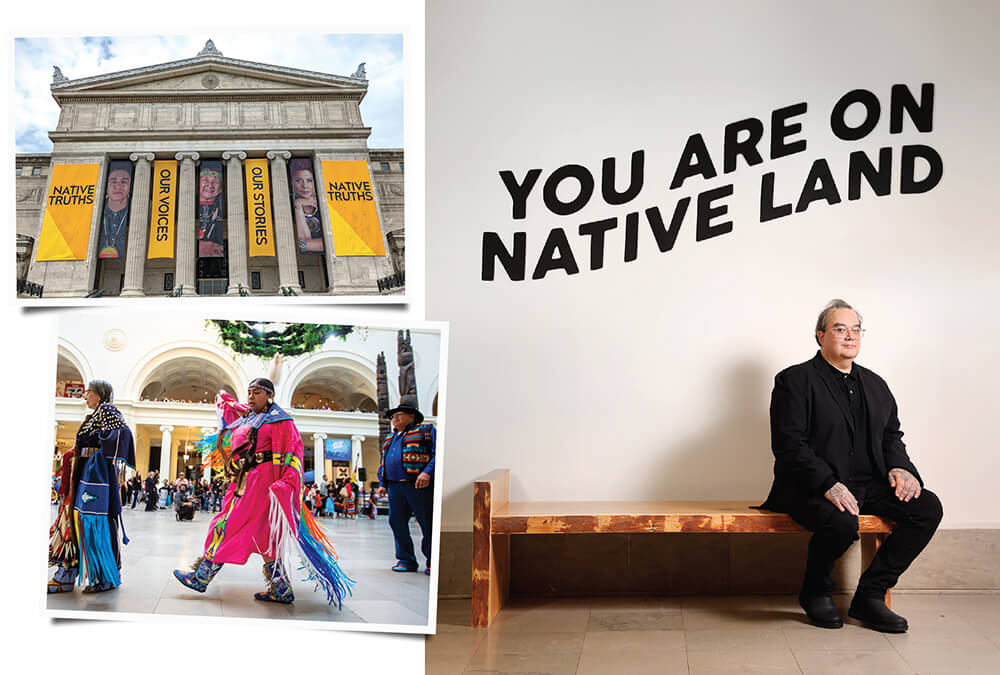

The greatest change, especially in recent years, is in the Field Museum’s approach to how it presents the history and culture of the diverse peoples reflected in its exhibitions and collections. “The world has changed,” Hoogstraten says. “George Floyd [and the subsequent heightened focus on racial justice and inequities] had a huge impact on the museum world. Now, especially with our cultural collections, we’re not speaking for people, but collaborating with them for them to tell their own story. That’s a real game changer in how we approach our work, now and in the future.”

When the museum embarked in 2018 on a complete overhaul of its badly outdated Native North American Hall, Hoogstraten traveled extensively—across the country and to the Te Papa museum in New Zealand—to observe how other institutions had successfully collaborated with indigenous communities. “The one thing we heard consistently was, ‘Don’t start your process without having your collaborators in place,’” he says. “Otherwise, you’re asking for buy-in and approval instead of organically creating a direction together.”

“With our cultural collections, we’re not speaking for people, but collaborating with them for them to tell their own story,” Hoogstraten says. “That’s a real game changer in how we approach our work, now and in the future.” (Images by Katrina Wittkamp; Courtesy of The Field Museum of Natural History)

Over the next four years, the exhibitions team and other museum staff worked with an advisory council of 11 Native American scholars and museum professionals and more than 130 other collaborators representing 105 tribes and nations. The resulting new permanent exhibition, “Native Truths: Our Voices, Our Stories,” which opened in May 2022, showcases how Native American culture is not a historical relic but a vibrant, varied and contemporary community of self-determination, resilience and continuity.

Those concepts shine through not just in the hall’s content but in its very design. The beautiful wooden floors and benches were made by Menominee Tribal Enterprises, the largest sustainable lumber operation in the U.S. The hall’s circular pod galleries, which resemble woven baskets, reflect indigenous concepts of time, not as linear but as a circle or spiral. The pods host rotating exhibitions on topics ranging from fry bread to Frank Waln, a Sicangu Lakota rapper and activist.

“I’m really proud of the exhibitions department because I watched them grow throughout the process,” says Debra Yepa-Pappan, Field Museum Native community engagement coordinator. “They did such an amazing job honoring the integrity of our stories.”

A broader range of stories are being shared elsewhere in the museum. A recent pop-up exhibit titled “Chicago’s Legacy Hula” celebrated 130 years of the Hawaiian dance form in Chicago. The “Africa Fashion” exhibition, which originated at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, will debut at the Field Museum in 2025 along with an accompanying gallery highlighting local Black fashion designers. The combination will serve as the first expression of Hoogstraten’s next major permanent installation: A new Africa Hall, slated to open in 2027 or 2028, will explore the myriad cultures on the African continent and place Egypt, not in the traditional Mediterranean context, but within the broader scope of Africa.

The new “Changing Face of Science” rotating gallery challenges visitors’ perceived notion of what a scientist looks like by sharing stories of women and people of color in science. It currently features Jingmai O’Connor, the self-described “punk-rock paleontologist” who is the Field Museum’s associate curator of fossil reptiles (and part of Team Sobek). She describes, in her own words, discovering her passion for paleontology at age 10 and her breakthrough excavations in China.

That gallery’s location directly across from the man-eating lions of Tsavo—one of the museum’s top attractions—makes it “something you discover as you’re walking through the gallery,” Hoogstraten says.

Hoogstraten still makes daily rounds of the museum to check on his department’s work. He especially enjoys visiting the newest exhibitions to gauge how people interact with the show and each other. “We test elements before we open,” he says, “but there is nothing like watching how real visitors react.

“If I’m feeling a little heavy, burdened by life, I just go downstairs and experience people having a good time. The museum is always where I want to be.”

Going Farther a-Field

Look for these six gems during your next visit

The Field Museum has more than 283,000 square feet of public space spread across three levels. Most visitors cover only a tiny fraction of that ground as they beat a path to the museum’s best-known attractions, such as SUE the T. rex or the mummies in the Inside Ancient Egypt gallery. But there are countless other treasures, big and small, that are often overlooked by visitors but well worth discovering.

As a museum insider, Jaap Hoogstraten, head of exhibitions, has assembled the following scavenger hunt to share some favorite and quirky sights and stops, and to encourage visitors to explore more of the Field’s fascinating holdings. See if you can spot these gems among the galleries.

![]() 1. CYRUS TANG HALL OF CHINA: A Field Museum curator in miniature

1. CYRUS TANG HALL OF CHINA: A Field Museum curator in miniature

The figurine in the denim shirt in this hall’s miniature excavation diorama is no generic model. It was made to resemble Gary Feinman, MacArthur Curator of Mesoamerican, Central American and East Asian Anthropology.

2. GRAINGER GALLERY: An out-of-this-world fossil

A highlight of the Grainger Gallery is an extremely rare fossilized meteorite. It splashed down in an ancient sea during the Ordovician Period (500 to 435 million years ago) and was discovered in a limestone quarry in Sweden in 1952.

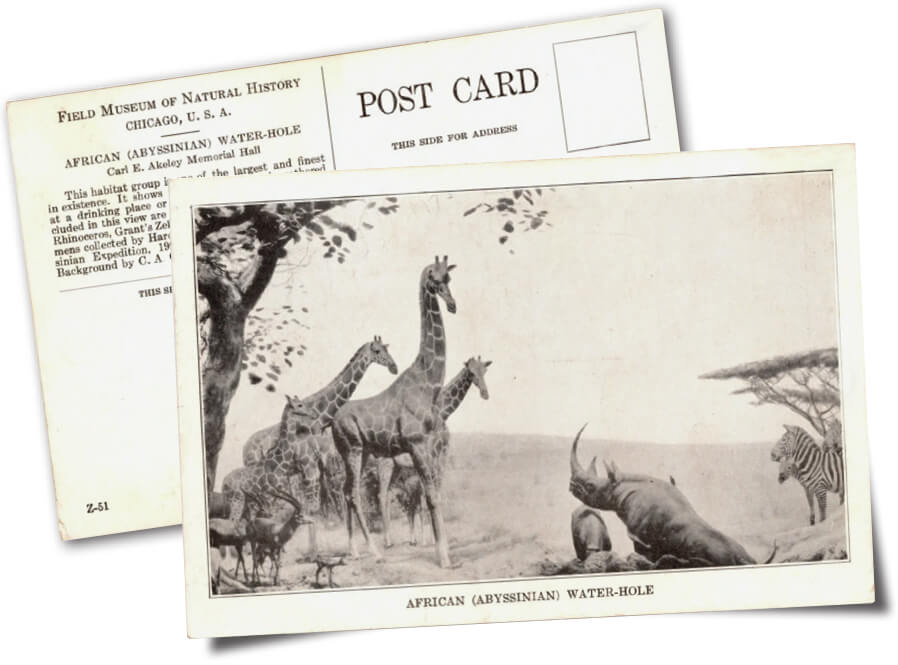

3. MAMMALS GALLERY: A wildlife diorama worth the walk

Built in 1932, the African waterhole scene is a stunning example of the Field Museum’s pioneering work in wildlife dioramas. The meticulously crafted landscape features 23 animals from six species drawn together around a crucial source of life: water.

4. GRIFFIN HALLS OF EVOLVING PLANET: A family member frozen in time

4. GRIFFIN HALLS OF EVOLVING PLANET: A family member frozen in time

One of the museum’s most Instagrammed spots is a sprawling collage of 131 photos capturing the diversity of life. There’s only one person in the collage, representing universal man: Daniel Hoogstraten, Jaap’s then-11-year-old nephew.

5. MULTIPLE SPOTS AROUND THE MUSEUM: Poetic license

Eric Elshtain, the Field Museum’s first poet in residence, has composed creative odes to wildly diverse items within the museum’s collections, such as “Dinkinesh, or, Lucy on the Brain,” and “Ode to a Coelacanth.” Look for his poems posted by their sources of inspiration—collect the whole set!

![]() 6. THE MACHINE INSIDE: Biomechanics: Have a heart

6. THE MACHINE INSIDE: Biomechanics: Have a heart

Just how hard does a giraffe’s heart have to work to pump blood all the way up those long necks? Discover for yourself in this hands-on display.

Home and Away

Touring shows defray costs

Sending shows on tour extends their life, defrays their cost and displays the exhibition team’s exceptional craftsmanship across the country. (Image courtesy of The Field Museum of Natural History)

One of the first exhibitions that Hoogstraten completed upon becoming the head of exhibitions in 2010 has come full circle. “The Machine Inside: Biomechanics” has returned to a permanent gallery in the Field Museum after traveling all across the country since its debut in 2014.

From the inside out, every living thing—including humans—is a machine built to survive, move and discover. “The Machine Inside: Biomechanics” investigates the marvels of natural engineering and gives visitors a highly interactive hands-on look into how animals survive. It also highlights technology inspired by nature’s ingenuity, such as Velcro, wind turbines and chainsaws.

“I love this exhibit because it has the specimens, science and storytelling of a natural history museum exhibition along with the fun and interactivity of a science center show,” Hoogstraten says.

Sending shows out on tour is part of the financial calculus of mounting most temporary exhibitions. “We plan for them to travel for a minimum of five years, and we try to have five or six traveling shows on the road at any given time,” Hoogstraten says. Current offerings include “SUE: The T. rex Experience,” “Antarctic Dinosaurs” and “Wild Color,” as well as the recently closed exhibitions, “First Kings of Europe” and “Death: Life’s Greatest Mystery.”