His Dream Job

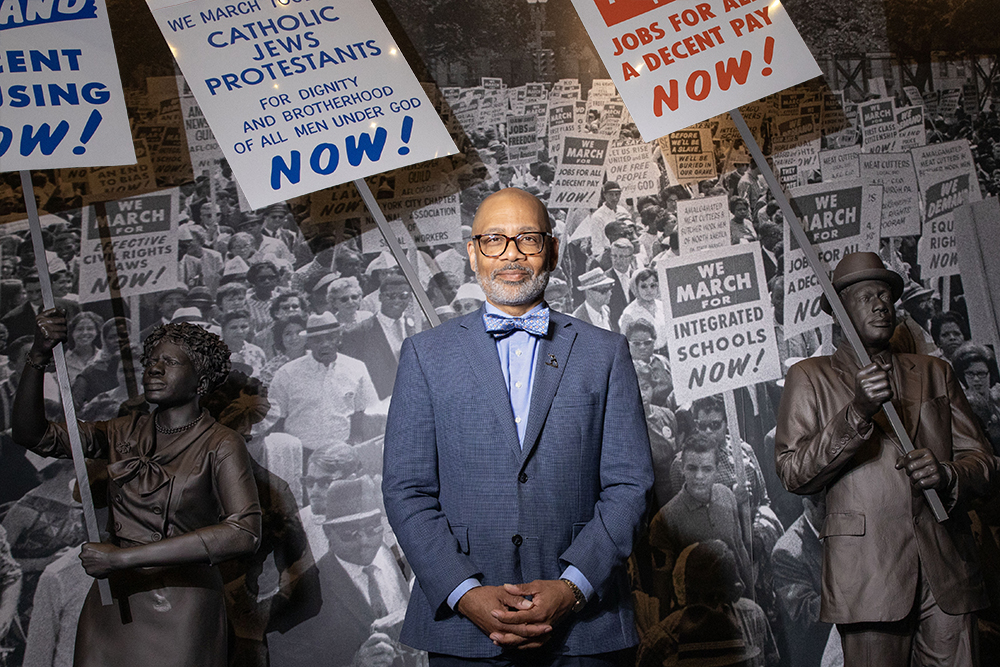

Dr. Russell Wigginton joined the board of the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tenn., in 2010, and became its president in 2021. (Image by Ariel Cobbert)

When Russell Wigginton, PHD ’01 LAS, walks into the National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel, he sees history.

Not just the history of African Americans and the struggle for civil rights in the U.S. Not just the millions of Africans transported as human chattel from Africa to the Americas. Not only nearly 250 years of slavery or the fight for those who had been enslaved and deemed fractions of human beings to be recognized as fully human and completely citizens.

But he sees his own family. He sees his history. He sees the future.

As the president of the National Civil Rights Museum, Wigginton wants others to see what he sees when they visit. The museum itself is a historical site. It is located at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tenn., the place where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968.

What does he want people to feel or do after they visit the museum?

“I want everybody who visits the museum to have a collision between their head and heart,” Wigginton says. “I want you to learn and relearn or clarify your learning about all manner of things. I am confident enough to say that I can guarantee that will happen at the National Civil Rights Museum.”

A native of Louisville, Ky., Wigginton has made Memphis his home for the last 28 years, and since 2021, served as president of the institution, the oldest civil rights museum in the nation.

Would he say it is his “dream job?” He thinks so, although he never thought about it that way.

“It’s a fascinating and beautiful culmination of my life and experiences to end up in this job,” Wigginton says.

As the museum prepares for a busy schedule of Black History Month events on a recent Friday in February, Wigginton sits across the street from the museum in his corner office of the administration building, reflecting on his journey.

“How I ended here I don’t think is an accident.”

One of his favorite parts of the museum is the lunch-counter exhibit, “Standing Up by Sitting Down: Student Sit-Ins 1960,” which tells the story of demonstrations by students who faced harassment and violence while desegregating lunch counters across the South. Four life-size bronze statues—two women and two men—sit at a lunch counter while two bronze statues stand to the side of them, depicting their tormentors who harassed and abused Black and white students who disobeyed segregation laws and demanded equal rights by daring to sit at the counters.

Wigginton’s mother was one of those students arrested for sitting at lunch counters in Louisville, Ky.

As a student, Wigginton’s mother participated in efforts to dismantle segregation laws and was arrested for sitting at lunch counters in Louisville, Ky. The lunch-counter exhibit is one of his favorite parts of the museum. (Image by Ariel Cobbert)

A few feet away from the lunch counter exhibit, there is a photo of Stokely Carmichael, who would later become a key leader of the Black Power Movement and change his name to Kwame Ture. In the photo, Carmichael wears a “Property of Howard Athletics” sweatshirt. The information next to the photo details how Carmichael followed the 1960 student sit-ins closely as a high school student in New York City, and when he enrolled at Howard University in Washington, D.C., that fall, joined the Nonviolent Action Group, a campus branch of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

What it doesn’t say is that Wigginton’s father and Carmichael were college suitemates for a time when his father attended Howard from 1960 to 1965.

Wigginton grew up hearing the stories of how his parents and their peers risked their lives registering voters in Mississippi and the peril of the simple act of sitting at a Woolworth’s counter.

His father came from a long line of African Americans who broke barriers in education. His paternal grandmother and all of her siblings were college graduates and earned their master’s degrees. His great grandfather attended the historical Black colleges and universities (HBUCs) of Fisk and Meharry Medical College in Nashville, and was the first African American physician in Jackson, Tenn., in the early 1900s.

His mother was the third of six children and lost her mother at the age of 6. At 18, she became the legal guardian of her 14- and 15-year-old brothers. Even with all of her responsibilities at that young age, Wigginton said his mother was a “freedom fighter” who courageously sat at the lunch counter and was arrested.

“I get the benefit of being their offspring,” says Wigginton, who looks at his parents as his most important role models. “So I grew up in this environment, that as I got older, came together in some interesting ways to shape how I think about the world, and how I tried to go about choosing the kind of work and life that I wanted to live.”

Wigginton’s father was a railroad executive for the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, known as the L&N, so Wigginton spent his early years in Louisville; then the family relocated to Nashville because of his father’s job. His mother worked as an executive administrative assistant and at times stayed home to take care of Wigginton and his sister, who was a few years younger, and his brother who was 13 years younger.

Growing up, Wigginton attended majority white Catholic schools for junior high and high school in Nashville. Although he came from a rich legacy of family members attending HBCUs, such as Howard and Fisk, when he graduated from high school in 1984, Wigginton decided to go to Rhodes College, a small liberal arts school in Memphis.

Wigginton, who had several scholarship offers to play basketball, chose Rhodes because he was seeking a smaller school with a strong academic reputation where he could also play basketball. Although Rhodes was a predominantly white institution, it was located in a city that “intrigued” him—Memphis, which was 65 percent Black.

“It didn’t matter the demographic of the college, frankly, if I was in a city like Memphis,” Wigginton says. “I had the benefit of playing basketball, being in an academically rigorous environment, being in a smaller school and being in a city where I could make sure that I was getting my cultural fulfillment met.”

He had “zero” idea of what he wanted to study, describing himself as being in “discovery mode” for a few years. At the end of his sophomore year, he landed on history as a major. He found that the skills of a history major—understanding trends, patterns and analysis—would deepen his knowledge of not just this country but the world and why things are the way they are.

“It wasn’t until I found that lane that all the pieces started coming together,” Wigginton says. “It’s almost like all of those personal and potentially intellectual and professional dots got connected.”

Those dots included his own family’s rich history.

On the other side of his father’s family, Wigginton had a great grandfather who was a red cap for the L&N Railroad for 50 years. Red caps were the baggage handlers who carried the luggage at the train station, akin to sky caps at an airport, Wigginton explains. He had the opportunity to get to know his great grandfather and was fascinated, even as a child, by this man’s life and the way the world saw him versus who he was in his own community.

“So if you think about the image of essentially an old Black man toting bags at a train station, the stereotypes that had been portrayed in our society around those people were not that they were uplifting. But I’m thinking, my great grandfather does that. He owns his own home. My great grandmother doesn’t work outside the home. They have a lovely home. They sent their kids to college,” Wigginton says. “This is a different world than what gets portrayed.

“I’m thinking this dude is toting bags in this space but he is this in this other world.”

By the time Wigginton arrived in Champaign-Urbana to pursue a Ph.D. in history, he already knew what the topic of his dissertation would be: “Black Railroad Workers from 1915–1945 for the Louisville and Nashville Railroad.”

He conducted a community and labor history study about men like his great grandfather who were perceived to be one thing in the work environment but were pillars of their own communities.

In December, “Lest We Forget … Images of the Black Civil Rights Movement,” a traveling exhibit showcasing 35 portraits by artist Robert Templeton, came to the National Civil Rights Museum for the first time. It is also the first exhibit that visitors are escorted to in the museum. The art captures key figures and moments from the civil rights movement, from the Niagara Movement, a civil rights organization founded in 1905 by W.E.B. DuBois and other activists, to the 1970s.

In one corner of the space is an oil painting of a man with a precisely trimmed mustache and thick wavy hair with gray around the edges. It is Whitney M. Young Jr., a civil rights leader and executive director of the National Urban League from 1961 until his death in 1971.

Wigginton says Young is part of the reason he came to the University of Illinois to earn a doctorate degree in history.

“I had this image of being the next Whitney Young,” says Wigginton, who studied labor history. Young navigated the corporate sector to open more opportunities for people, particularly people of color, and that was the space where Wigginton wanted to operate.

After college, Wigginton, who had earned the equivalent of a minor in business, went to work in sales and marketing for the Oscar Mayer food company and had risen through the ranks. He was poised to be one of a handful of Black district managers in the country when he surprised his managers and parents by leaving his lucrative job to pursue a doctoral degree in history.

“I left that nice paycheck to be a poor graduate student and never had one day of regret,” Wigginton says.

As a 26-year-old graduate student who had worked in the corporate world, he was “laser focused.” He chose the University of Illinois because of its reputation and ranking as one of the nation’s top history programs. Wigginton worked with athletes in the Bridge Transition Program as an academic adviser. He had the opportunity to work with future U of I Athletics Hall of Fame football players Simeon Rice, ’96 LAS, and Kevin Hardy, ’11 LAS, both of whom became NFL players.

Wigginton’s advisors, professors and mentors included Dan Littlefield, who oversaw his dissertation, Orville Vernon Burton, James An-derson, EDM ’69, PHD ’73 LAS, and Jim Barrett, ’72 UIC. At the very beginning of his dissertation, he accepted a fellowship at his alma mater Rhodes College and finished his dissertation off campus. In the mid-1990s that meant mailing chapters to his committee via the U.S. Postal Service and saving work on floppy disks. With all the moving parts and not being on campus, Wigginton says it would have been easy for him to be forgotten and fall through the cracks, but the faculty supported him through the process.

“I was blessed to have people who cared deeply about me and invested in me and made me a better scholar,” Wigginton says. “I have great admiration and appreciation for those folks.”

Room 306. This is the place where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spent his last hours, unaware that in the boarding house across Mulberry Street an assassin lay in wait to take his life. It is the last stop in the museum tour, a sacred spot, preserved behind glass to look like that fateful day.

A framed replica of the Room 306 door hangs in Wigginton’s office, a reminder of the museum’s mission to honor and preserve King’s legacy.

But the complex of buildings—which includes the former boarding house across the street where assassin James Earl Ray had a room and The Legacy exhibits that explore the lingering questions about King’s assassination—is more than just a memorial. The museum also has a mission to chronicle the American civil rights movement and the ongoing struggle for human rights.

“This is not a 15-minute walk up to the balcony. That’s not what this is. This is a comprehensive look at civil and human rights in this country beginning with slavery, and we walk you all the way through and we talk about people you never heard of who are really the heroes and heroines of the Movement,” Wigginton says.

“I want everybody who visits the museum to have a collision between their head and heart,” Wigginton says. (Image by Ariel Cobbert)

Every day, Wigginton says he sees people who visit the museum show a range of emotions—from sadness and anger to hope and inspiration. About 300,000 visitors, 40,000 from outside of the U.S., come to the museum every year.

Wigginton’s relationship with the museum, which opened in 1991, started in 1996 when he returned to Memphis to work at Rhodes. There, he was developing a course on civil rights history and started a relationship with the museum, including an internship program for Rhodes students. He worked at Rhodes for 23 years as a professor and then an administrator. In 2010, he joined the museum’s board, and in 2021, became its president.

The museum is poised to go to another level in its work, and that work is even more critical as the nation faces forces that want to stifle the teaching of history, rebrand slavery and avoid the uncomfortable conversations.

“This stuff is uncomfortable for everybody,” Wigginton says. “What we cannot do is take 250 years of our nation’s history and pick and choose a few parts that we want to talk about and tuck the rest of it under the rug and act like it has nothing to do with the 150 plus years subsequent. That never allows the elephant in the room to go away.”

The museum is currently conducting a $55 million capital campaign called “Become the Dream.” The focus of the renovation comes from the title of King’s last book, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community. The projects that the campaign will fund include a $36 million renovation of the boarding house and park across the street to expand the civil rights narrative beyond 1968. Wigginton wants more people to make the connections between

what happened in the past and what is happening now and find inspiration.

He never dreamed of being president of the National Civil Rights Museum, but all of his history, experience and passion make it the perfect place for him to be.

“I’ve had the tremendous privilege of doing work that was both personally and professionally fulfilling. Even on challenging days and times, it has always been fulfilling,” Wigginton says. “My whole career has been a dream job.”