The Aha Moments

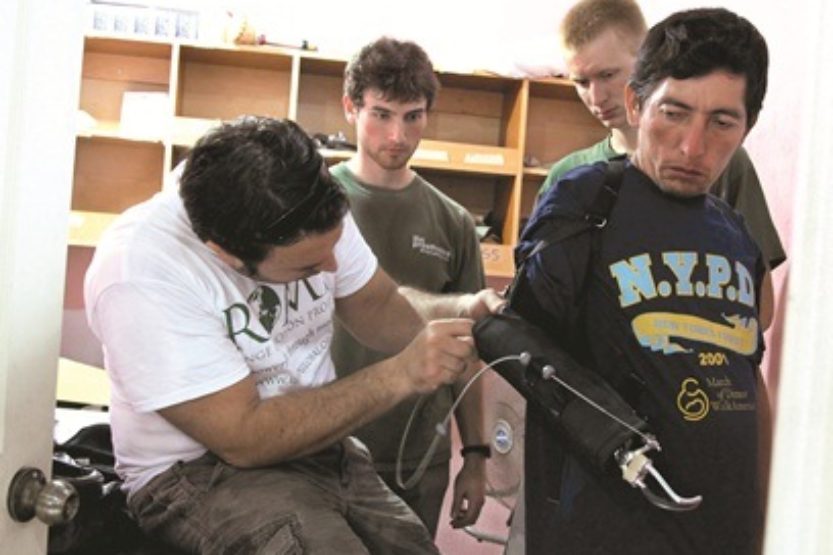

Jonathan Naber, center, and Adam Booher, right rear.

Photo courtesy of Bump

Jonathan Naber, center, and Adam Booher, right rear.

Photo courtesy of Bump The University of Illinois has long been a place where ideas come to be born, a crucible for the life and products of the mind, from novels to Nobels, technology to theory, practical applications of agriculture to the furthest glimpses into the structure and meaning of the universe.

Now as never before, inspiration is emanating not only from those who teach and do research at Illinois but from those who study here. More and more ideas are germinating and taking root among students and recent alumni, yielding collaborations and business plans and licensing and patents and products that work, often for the greater good.

As Goethe once observed: “Daring ideas are like chessmen moved forward: They may be beaten, but they may start a winning game.” What follow are the stories of six such gambits and the intrepid Illini who are moving the pieces forward.

Arms for the world

For Jonathan Naber ’11 ENG, the idea for the arm came when he was a sophomore, in a rush of altruism. He was contemplating an item called the Jaipur Foot and the statistics that produced it: 20 million people in the developing world are estimated to be missing limbs, with 90 percent of those having lost their legs. Hence the Jaipur Foot, a simple rubber prosthetic developed in India that costs approximately $28 and is distributed there and in countries worldwide.

But what, the young man wondered, about arms?

Naber put the problem to his friend Adam Booher ’11 ENG, and the two engineering students started raiding recycling bins and dumpsters, looking for expendables and disposables that could be used to fashion an inexpensive prosthetic arm. That was four years ago. Today, their company, Bump, is headquartered at EnterpriseWorks, a business incubator in the UI Research Park. Using an old, heavy-duty Singer sewing machine salvaged from someone’s aunt’s barn, Booher and other members of the growing company stitch together OpenSocket prosthetic arms, which come in small, medium and large sizes and can be fitted and tightened using an ingenious design that Booher likens to “the tongue in a shoe.”

As for Naber, he’s been spending more or less all of his time in Central America, where Bump has established its presence at several clinics (an effort launched in 2010 with the help of David Krupa’02 LAS, a biology major who has pioneered services for amputees in Central and South America).

At $300 base price, the Bump OpenSocket isn’t so inexpensive as the Jaipur Foot, but it is far cheaper than a custom-fitted model. Support has come through grants and awards, and the Rotary Club has in place a sponsorship program through which donors can fund arms for those in need. Beyond the countries of Central America await developing nations throughout the world. Need is so great, says Naber, that Bump will never be able to meet it.

But the work is a start. At press time, 40 amputees in Central America and India have OpenSocket arms in place of limbs lost, mostly in accidents and other traumatic incidents, and a team of prosthetists will shortly introduce the arms in Sierra Leone. When a patient is fitted with a limb, Naber observes, “sometimes the families cry because they’re so excited.”

Spin story

As an undergraduate, Scott Daigle ’09 ENG, MS ’11 ENG, became quickly and painfully aware of the Urbana campus as “a big place where everybody has to get around” – including people who do not have the use of their legs. Partnering with Marissa Siebel, a UI doctoral student who trains wheelchair athletes, Daigle formed a company called IntelliWheels and set about designing a wheelchair with gears.

The outcome of several iterations over several years, the IntelliWheels Easy Push is a set of wheels that fits any standard wheelchair. An Easy Push moves in low gear when the person seated pushes on the wheels. Moving the outer rims of the wheels engages an ingenious geared system with a 2-to-1 ratio, allowing the chair to, in effect, roll forward twice as easily.

Backed by more than $500,000 in venture capital funding and awards from grants and competitions, IntelliWheels is headquartered in EnterpriseWorks (where, until recently, it shared space with Bump). Daigle and Siebel have been joined by Josh George ’07 MEDIA, a Paralympian gold medalist who directs their marketing. Things look good for the business plan. The Easy Push is patent pending and has been approved for Medicare reimbursement. Twenty-five sets of wheels went on the market in January, targeted to residents of nursing homes and assisted-living facilities. Next project: a manual-shift version with three to five gears.

“The sky’s the limit,” says Daigle.

“People have worked on geared wheelchairs before,” he adds. “But we think we’re the first to do it right.”

Growing pains

Steve Heiss chose a practical major – perhaps the most practical major – when he entered the University’s highly rated accountancy program. In May, he will stride away with his degree, pointed toward Chicago and a job in consulting with Price-waterhouseCoopers. He’ll also leave behind a garden. This is not a totally good thing.

The garden came about through an annual competition sponsored by the accountancy firm Ernst & Young, which offers three awards nationally for business plans designed to make a difference in the community. Heiss and his interdisciplinary student team laid out their idea to create C-U Garden in a north Champaign park near an elementary school where 90 percent of students qualify for federally subsidized lunches. As Heiss and his team envisioned it, the garden would flourish on several levels. Pupils would study the plants, following a curriculum written as part of the project. The school cafeteria would serve the vegetables. More produce was to be sold at a farm stand, proceeds to benefit the community. Inexpensive individual plots ($10 for a season) were available to neighborhood residents.

The plan won the competition in March 2010, netting a $10,000 award. Press releases were sent and photos taken. Illinois Gov. Pat Quinn and First Lady Michelle Obama expressed support. Ground was broken, boxes built, a shed put up, seeds planted.

Then real life began to happen.

That fall, vandals smashed the garden’s crop of pumpkins and broke open the shed, tearing holes in the door and the roof. Worse, someone permanently removed a water pipe that was critical to the garden’s survival. A project that Heiss envisioned as a national model – schools could purchase the curriculum he and his team developed, which was the beauty of the whole thing as a business plan – receded into timbered boxes full of weeds with a broken shed in the background.

Currently, Heiss is at work on a succession plan, seeking partners to take over the garden and get it growing again. He fears the project could otherwise become for north Champaign “one more project in a series of projects of privileged University students coming and saying, ‘This is right for you.’”

But whatever grows or withers and dies, when Steve Heiss is at his desk in Chicago, he can remember the business he founded for a good purpose and a garden dug on a beautiful spring day by people from all over the community and the University.

“There is no other thing I’ve done on campus that has given me the life lessons that have come from this,” he concludes, and while his eyes are pained, his smile remains wide.

Fresh idea

For Zeba Samad Parkar, PHD ’11 ENG, ingenuity turned out to be a family affair.

Parkar came to the United States in 2006 from Mumbai, India, to study materials science and engineering at Illinois. When her father, the dean of Bombay Veterinary College, came to visit, she brought him to her workplace to meet her mentor, UI professor James Economy, an expert in water purification.

“All three of us were talking about materials that can kill bacteria in water,” Parkar recalls.

“My dad said, ‘We have a problem [preserving] milk in India – can this [process] be tailored for food products?’”

Parkar took her father up on his suggestion, and within two weeks concluded it “might have some promise.” Thus was born Milkshield, a simple insert that can be placed in any container of milk to preserve it for up to 72 hours at temperatures up to 100 degrees. For farmers in India, who routinely sell milk from the few cows they own for their livelihood, a spoiled product means the family goes hungry.

As Parkar refined the technology, her husband, Nihal Parkar, MS ’10 (UIC), got involved. With a background in food science and chemical engineering, he supervised the quality and taste of milk that had been exposed to the shield, which is a screen injected with nanoparticles of silver, known for its anti-microbial properties.

The University continued to play a part in Parkar’s venture. She co-founded Silverscreen, a company to commercialize the idea (with Economy), and received funding, networking opportunities and lab space at the UI Research Park via Illinois Launch, a program that supports entrepreneurship. UI business students helped with financial planning, while law students drafted the first patent proposal.

While Milkshield remains in a transitional phase, Parkar’s flair for ingenuity is continually honed at her current job at 3M in Minneapolis, where she is a research engineer. Every day, Parkar says, she strives to “invent something for the common people, something that’s useful. I try to get funding, try to get interest. So I continue to be [an entrepreneur].”

For Zeba Parkar, fresh ideas never stop.

Objects lesson

Kevin Karsch not being a young man inclined to aha moments, his genius idea – and “genius” does not seem to be an exaggeration – took shape over a period of years, beginning with his undergraduate career at the University of Missouri, where he studied computer science because he wanted to make video games. Heading to Illinois to continue computer studies in doctoral mode at the College of Engineering, he encountered computer science professors Derek Hoiem and David Forsyth, who pointed him toward work in 3-D computer graphics. The upshot has been the development of a program of eerie character and profound implications.

Karsch can take a digital photograph and electronically insert one or more objects into it, creating a completely convincing but essentially fictional new version of the image. He has written software that adapts the photos, proportioning and lighting the new objects, materializing each in a manner that recalls a David Copperfield magical appearance in reverse – now you don’t see it, now you do.

When refined and streamlined, the technology could prove useful to, among others, furniture companies (how would that IKEA sofa look in the living room?), educators (the Colosseum in its heyday pictured in the cityscape of modern Rome, for example) and photographers (camera viewfinders that one day could allow selection and insertion of an object into a picture – Grandma, say, or the dog).

Far beyond such practical applications, though, Karsch’s research is about teaching computers how to see by delineating the parameters of photographic imagery. “If we can get a robot to understand a scene by taking a picture of it,” he explains, “the robot can then try to figure out how to move in that scene.” Difficult to grasp, yes, but an obvious advance over the Roomba.

And a big leap past Photoshop – an observation not lost on Adobe. The visual software company licensed Karsch’s technology from the University and hired him as an intern.

And that, for now, is as close to the business world as Karsch intends to get. “A startup is a lingering possibility,” he says. “But first I want to finish my doctorate.”

The EasyGo guys

The aha moment arrived on an Army plane making the long, long flight back from Afghanistan. Blake Schroedter ’08 LAS had been deployed there for a year, and when he came back out of the dust and blood, he was thinking about, well, protein shakes. Soldiers in the field stay alive on them, cutting the bottom off of an empty water bottle to serve as a funnel, then pouring the powder through it and into a second bottle containing water. Shake, quaff, toss, go. Efficient but messy. Couldn’t there be, Schroedter asked himself as he sat on the plane, a better way?

He teamed up with two other Illinois National Guard members: Mike Pett ’07 LAS, an old chum from the U of I and, beyond that, from Iraq; and Tony Genovese, a comrade from Afghanistan. The three brainstormed the EasyGo Pro, a container that stores, measures and dispenses protein powder. (The bottle of water still forms the disposable end of the process.)

They’ve been at work on the company for more than three years, funding it with their own money and soliciting pre-orders on Kickstarter (a website for entrepreneurs seeking support for their ideas). Through the Cozad New Venture Competition on campus, the trio got space in EnterpriseWorks; their operation has since moved to Chicago, where all three live, work and study. (Genovese is a student at the University of Illinois at Chicago.) When EasyGo launched in October, “we hit the ground running,” Schroedter says.

Unfortunately for the business plan, conflict of interest rules enjoin direct sales to the military. (A special program does allow folks back home to purchase individual dispensers for personnel in the field, and approximately 100 have made their way to Afghanistan.) The guys are shaking out plenty of market potential elsewhere, including bodybuilders, dieters and post-op bariatric surgery patients who aren’t allowed solid food. To date, EasyGo has sold more than 500 units in the U.S., Canada and Australia. The diminutive EasyGo Baby, specially created for mixing infant formula, is in design and expected to go on the market this spring.

Thanks to teamwork learned in the Army, Pett says, “at the end of the day we know how to get the job done,” while acknowledging “loss of sleep and fear of the unknown.”

Kind of like a soldier in the field.

Bringing it on

Such stories may never have happened without a cross-campus array of resources, from the encouragement of professors to the various programs and centers that support new University-related business ventures.

Hosted by the College of Engineering, the Technology Entrepreneur Center is an engine for startups. The College of Business houses the Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership as well as the Social Entrepreneurship Institute. Business students can also pursue course work and a major in entrepreneurship.

The Research Park nurtures student startups with space in a supportive environment. The National Center for Supercomputing Applications recently announced the launch of SPIN (Students Pushing Innovation), offering mentors and internships.

The annual Lemelson-MIT Illinois Student Prize carries a $30,000 award and has become synonymous with excellence in ideas and entrepreneurship. Prizes went to Naber (of Bump), Daigle (of IntelliWheels) and Karsch in 2010, 2011 and 2012, respectively.