Shakespeare In The Cellblock

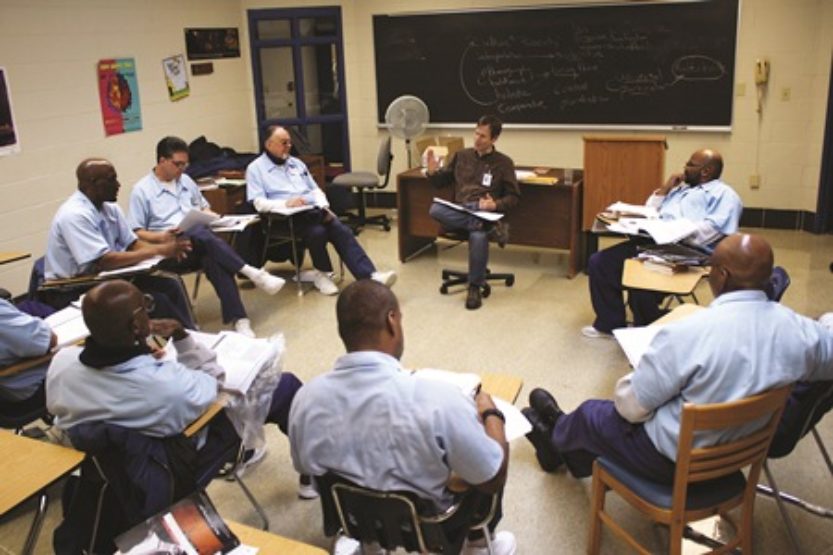

An anthropology course at Danville Correctional Center.

An anthropology course at Danville Correctional Center. Approximately 40 miles east of the University of Illinois campus sits a tight configuration of hard-angled buildings surrounded by fields. If you approach this place in the evening, as do many members of the Education Justice Project, you might not know what it is until you come close.

That’s when you see the tall fences and gleaming coils of wire, the looming guard towers. This is Danville Correctional Center, a medium-security prison home to 1,800 male inmates, including some of the most dedicated UI students you can find.

One rainy December evening, 60-some inmates – students – dressed in the standard “state blues” and bright white sneakers gather in the chapel of the correctional center to meet with members of the Education Justice Project, a robust, volunteer-based program initiated at the University of Illinois in 2006 to bring upper-level college education to the prison.

This was an organizational meeting, with curricula, scholarships and new programs on the agenda. There were no guards in the room. Speakers were greeted with loud applause, with the loudest reserved for a slim, soft-spoken woman named Rebecca Ginsburg.

Ginsburg, a UI professor of education policy organization and landscape architecture, co-founded EJP and serves as its director. Possessing a striking visage and a powerful belief in the value of a solid education, she came to Illinois from the University of California Berkeley, where she worked as a graduate student in a similar program at San Quentin State Prison.

Ginsburg’s efforts, along with those of the roughly 60 faculty, staff, students and other volunteers, are fueled by their concern over the societal impact of the cost of incarceration and the financial and emotional effects on prisoners’ families and communities – currently, some 2.3 million people in the U.S. sit behind bars, with millions more who have been released from prison facing an uncertain future. EJP volunteers believe in-prison education is a prime tool to address those issues.

A “win-win” situation

The chapel buzzes. It is no small achievement to be part of EJP. If an inmate wants to join, first he must have a high school diploma or its equivalent (and many don’t, with the average DCC inmate entering prison with a sixth-grade reading ability), along with at least 60 college credit hours, the same as a UI transfer student.

The credits can be earned through the prison’s community college programs, which provide 100- and 200-level courses. Although the state of Illinois had a long history of being in the forefront of offering higher education in prisons, says Ginsburg, today the only place where inmates can receive upper-level classes is at the Danville facility. Currently, approximately 100 inmates are enrolled.

EJP brings many academic opportunities to the prison, from science, cultural and writing workshops to courses in history, statistics, linguistics, engineering and how to teach English as a second language. Inmates have performed theater and organized art exhibits that feature their work on the UI campus. There is talk of learning media production through a new EJP program being aired on community radio in Urbana.

EJP, which is funded entirely by grants and donations, cannot yet offer degrees, but inmates are awarded college credit.

Through year-round course offerings, workshops, discussion groups and other efforts, EJP has earned deep respect – from inmates all the way up to administrators at the Illinois Department of Corrections.

Instructors talk about the project as changing “their orientation to the world, the way they teach, the way they learn, their ideas about who they are and what they can accomplish,” Ginsburg says with passion.

As for the inmates, “EJP opens up a whole new world to students, where achievement and opportunity exist,” says Debbie Denning ’84 (UIS), DOC’s chief of programs and support services. “That’s generally not within their realm of being, especially when they’re in prison. It’s not often that a major university knocks on our door and offers us the opportunity to have free programs and upper-level education opportunities.” Denning calls EJP a “win-win” for everyone.

That includes the University, whose land-grant mission involves engaging with the outer community. EJP’s engagement, says Ginsburg, is both moral and strategic, as studies prove that an uneducated population is a drain on society.

Engaged and focused

They come from various backgrounds, from young men to those who’d gone gray behind bars. Among the students is Samuel Santiago, 40, standing 6 feet tall and weighing roughly 250 pounds. With his shaved head, he would be intimidating but for his thoughtful demeanor.

EJP volunteers say they seldom speak with students about why they are in prison, but the inmates can be so friendly that it begs the question. When Santiago was 18, his life embroiled in drugs and gangs, “someone got hurt real bad,” he says.

He reconsiders the phrase and adds, “Somebody lost their life.” He has been under maximum or medium security ever since.

Today, Santiago’s path to redemption includes Shakespeare, theater, film noir and classes in education, all of them provided by EJP.

“After being in maximum security for so long, you become jaded,” Santiago says. “Being in EJP, it allows you to stimulate your mind and reminds you of the good nature of society.”

Ginsburg emphasizes that the inmates’ course work is evaluated in the same way as that of students at the Urbana campus, and that on the whole, the inmates’ work is on par with typical undergraduates. She points out that in a landscape design class taught last semester, Urbana students took the top and bottom marks, with Danville inmates enrolled in the same class falling in the middle.

EJP instructors add that the absence of smartphones and other distractions banned by prison rules, along with a sense of purpose among inmates who view education as key to overcoming their past, helps create particularly focused class environments – so focused, in fact, that one EJP instructor handed out a syllabus the first week of class and upon his return a week later, found that his students had already completed the list of readings.

With half of EJP instructors being female, the women volunteers say they feel safe teaching in a prison environment. Rachel Rasmussen, EJP’s tutor coordinator, and Nicole Brown, a UI doctoral student in sociology, taught an EJP class on feminist theory and say that, aside from the necessity of abiding by prison rules, their sessions felt like a normal, albeit lively, classroom.

The women say that one of their favorite moments in the discussion group came at the start of class. Students would file in and take their seats around the circle of chairs. The guard would leave, the door would close, and for the next three hours, it wasn’t a prison – it was a discussion.

And other behaviors rise to the fore as well.

“Every time I so much as pick up a Kleenex box, they run across, saying, ‘Let me carry that for you,’” Rasmussen says. When you’re incarcerated, “you don’t get to give anymore. … It’s interesting how meaningful it becomes for them to do something for someone else.”

At one time, programs like EJP were widespread, Ginsburg says. In 1994, however, the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act eliminated Pell Grants for prisoners. Stripped of their funding source, hundreds of college prison programs closed over the next decade, including all in Illinois that offered baccalaureates. Today only a handful of programs like EJP remains.

‘People are good’

Back in the chapel that December evening, the meeting runs two hours

and ends as the inmates say goodbye to the EJP volunteers.

“We have a tremendous respect and admiration for the instructors,” Santiago says, before heading back to the cellblock with the others. “It reminds you that people are good.”

Ginsburg says that when Santiago first joined EJP, he was hard to read. He was quiet, she recalls, and it was difficult to tell if he cared.

But she would soon learn that, like so many of the others, he did.

He was quiet because he listened very closely.

Evensen is a freelance writer in Champaign.

Learn more about the Education Justice Project.