Learning and labor

Late autumn afternoon on the Quad. (By L. Brian Stauffer)

Late autumn afternoon on the Quad. (By L. Brian Stauffer) The University of Illinois’ history is reflected in our nation’s history. Founded in 1867 as Illinois Industrial University, it traces its origins back before statehood. In 1787, Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance, which established a public obligation for education. Declaring that “religion, morality and knowledge, being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged,” Congress set aside a square-mile section in each township to fund public education. It was up to each new state to decide what to do with it.

Illinois quickly became a crossroads. Stretching almost 400 miles from north to south, almost as far north as Boston and farther south than Richmond, Va., the territory was first settled along the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, with the population moving from south to north and from west to east. Urbana-Champaign was one of the last places to be settled.

Classes began on March 2, 1868. The University offered students courses in liberal arts and practical education in industrial classes.

Competing ideas, opportunities and traditions shaped the new state, as they would the new university. Five states were carved out of the Northwest Territory: Ohio (in 1803), Indiana (1816), Illinois (1818), Michigan (1837) and Wisconsin (1848), along with the northeast part of Minnesota (1858). Each state had its own approach to higher education. The Ohio University was chartered a year after Ohio became a state. Indiana University was established in 1820, four years after statehood. Wisconsin became a state and founded its university the same year, and the University of Michigan began 20 years before statehood. Historians have lamented Illinois’ “unique educational backwardness,” yet this overlooks Illinois’ pioneering of a competitive “system” of public and private higher education. Eastern states, such as Massachusetts, are still dominated by private universities; there are only a few strong private universities outside of the Northeast. Illinois is a major exception, with two public and two private research universities, one of the few such states in the nation.

In the East, higher education was almost entirely private and based on a classical liberal-arts curriculum, and Illinois initially followed this development. The first college in Illinois was Rock Spring Seminary, an institution for training teachers and preachers, in 1827. It was followed by McKendree, which was founded near St. Louis in 1828 by Methodists. Other colleges—all on the classical model—quickly followed, sponsored by different denominations. Methodists added a second college, Northwestern, in 1851, and Baptists followed with the first University of Chicago in 1857. Illinois had more than 20 colleges by the time of the Civil War, and this competitive environment shaped the history of Illinois’ public university.

Industrial Education

Jonathan Baldwin Turner (1805–1899) championed a different educational movement. Originally from Massachusetts, Turner studied classics at Yale and became a professor at Illinois College in 1833. He was an early abolitionist and agricultural scientist, leaving the school in 1848 to call for a new type of university, for “liberal education for the industrial classes.” Turner advocated for the teaching of practical subjects, especially agriculture, rather than classics, to produce “the finest products and greatest amount of human wealth with the least amount of human toil.” His was the vision of the Jeffersonian yeoman farmer and industrial artisan educated through science. Turner sought allies across Illinois, but also joined with proponents of a teacher-training institute to have the General Assembly create the Illinois State Normal University in 1857.

Turner’s idea was to have the federal government give public lands to fund industrial colleges in each state. He drafted a resolution, passed by the Illinois legislature, for its congressional delegation to introduce a land-grant bill. Unfortunately, that plan fell through, delaying the industrial education movement. In 1857, Vermont representative Justin Smith Morrill (1810-1898) introduced his own bill for land-grant colleges. Passed in 1859, the bill was vetoed by President James Buchanan. Three years later, with the Civil War raging and President Abraham Lincoln in office, a lightly revised version of the bill was re-introduced by Morrill. With the southern states out of the Union, President Lincoln signed the Land-Grant Agricultural and Mechanical College Act on July 2, 1862. As its name implies, the law gave federal lands to states, apportioned by the number of federal senators and representatives, for colleges “without excluding other scientific and classical studies and including military tactics to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts, in such manner as the legislatures of the states may respectively prescribe, in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions in life.”

States were not required to use such funds for public universities. New York endowed private Cornell University; Massachusetts supported the private MIT, although most states used them for public institutions.

With the passage of the act, Illinois was in a position to fulfill the vision of a university for “agriculture and the mechanic arts.” But how should the grant be distributed? As one historian put it, “Rival groups gathered like sharks around the carcass of the land grant, and Illinois Industrial University received its baptism in bloody political waters.” Chicago made a strong attempt to bring the “mechanic arts” to its industrial workers, leaving agriculture to downstate. Other regions called for the creation of two agricultural schools in the northern and southern parts of the state.

The General Assembly convened in 1867, besieged by various claimants for the land grant and for other state largess: Chicago wanted to develop its park system; Springfield wanted a new statehouse; southern Illinois wanted a penitentiary; and private colleges wanted to divide the land grant. Rather than decide itself, the legislature put the location up for bid. Four regions responded: Bloomington, Jacksonville, Lincoln and Urbana. Through legislative log-rolling, and buoyed both by the railroads and by pleas that it was the least-developed region in the state, Urbana won.

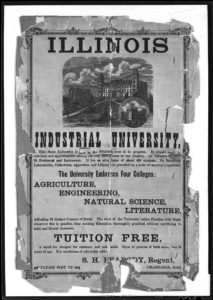

Establishing a university

The statute creating Illinois Industrial University emphasized the institution’s difference from a classical college. The trustees were to manage it so as “to teach, in the most thorough manner, such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts, and military tactics, without excluding other scientific and classical studies.” Rather than degrees and diplomas, students would receive “certificates of scholarship” in “the English language.” The senior academic officer was called the “regent,” as “president” was thought to be too classical. Matriculates had to be at least 15 years old and pass an exam in “common-school subjects.”

The trustees selected John Milton Gregory (1822–1898) as the first regent. A graduate of Union College in Schenectady, N.Y., Gregory started out practicing law and then became a Baptist minister before heading a classical college. He became Michigan’s superintendent for public instruction just before the Civil War and served as president of Kalamazoo College. The choice of Gregory disappointed many leaders of the industrial-education movement, leading Turner to lament, “O Lord, how long, how long? An ex-superintendent of public instruction and a Baptist preacher! Could anything be worse?” Gregory would, however, lay the foundation for a comprehensive university.

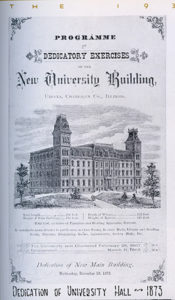

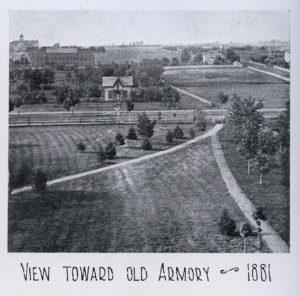

Classes began on March 2, 1868, with approximately 50 male students and two faculty members plus Gregory, in one grand, five-story building on the prairie, located on the banks of Boneyard Creek. The inaugural ceremonies were held on March 11, 1868, with an anthem written by Gregory: “And Learning and Labor—fit head for fit hand—Shall crown with twin glories our broad prairie land.” (The University’s motto is drawn from the anthem.)

In his inaugural address, Gregory reversed the order of the land-grant act, calling for “the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes.” He wanted to “unite scientific and art education—to make true scholars, while we make practical artisans, and to do this, not in one or two arts, but in the whole round of human industries.” Dismissing “mere book learning,” he insisted that “practical” education included the liberal arts. Praising discoverers and inventors, he pointed to a broader view: “Besides the workers in physical things, there are those who work in the great realms of social and spiritual life—who culture the soul to higher power and arm it with nobler purposes. Are not these, also, practical? Are not ideas possessions, as well as cornfields? Is not beauty a marketable quality, even in a horse?” Speaking to rural people, Gregory claimed that the “most practical thing on earth is brain power—the power to see, reason and understand. That education is most practical which most develops brain power—power to perceive, judge and act.” He concluded with a flourish: “Let us but demonstrate that the highest culture is compatible with the active purpose of industry, and that the richest learning will pay in a cornfield or a carpenter’s shop, and we have made universal education not only a possible possession, but a fated necessity of the race.”

John Milton Gregory’s grave between Altgeld Hall and the David Dodds Henry Administration Building. (Courtesy of UI Public Affairs)

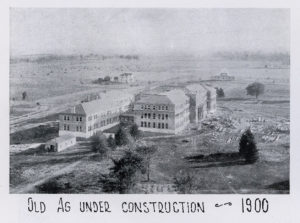

Illinois Industrial University grew slowly in its early years. Early colleges included Agriculture, Engineering, Natural Science, and Literature and Science. Most students took courses in engineering or other practical fields. Still, Gregory’s insistence on including liberal arts in a comprehensive curriculum was deeply controversial among those who advocated for industrial education. Early on, few students took the agricultural course, for which critics held Gregory responsible, but agriculture had yet to develop into a scientific discipline. That had to wait until Professor Manly Miles (1826–98) established his experimental plots on campus in 1876—the first such fields in the U.S.

Two years after the University opened, the first women students were admitted, and in 1874, the School of Domestic Science—the first of its kind—opened to educate women in “the arts of the household,” including chemistry, botany and dietetics.

The 1870s were difficult for the University. Enrollment remained flat through most of the decade at about 400 students, and land sales failed to bring in enough money for the endowment. Deficits were absorbed by cutting faculty salaries, and the trustees did not affirm the regent’s larger vision. Gregory had grown more convinced of the value of the emerging German research model and wanted the state to have a true university, “where knowledge and science are discovered and perfected, as well as a center for its dissemination.” While not yet using the word “research,” Gregory wanted Illinois to be part of the transformation that created the modern university. But his vision of a comprehensive university spread the young institution’s limited resources too thin.

While Gregory had early on encouraged student government, students grew restless over compulsory chapel and military drills, along with the ban on fraternities and other social activities. Such unrest, coupled with continuing clashes with trustees and legislators, led Gregory to resign in 1880. His wishes were to be buried on campus, and he rests near Altgeld Hall, under a marker inscribed, “If you seek his monument look about you.”

Peabody and Burrill

In 1878, Gregory had hired Selim Hobart Peabody (1829–1903) as a professor of mechanical engineering and physics, in what was becoming one of the best engineering schools in the nation. On Gregory’s resignation, the trustees appointed Peabody regent. The University was in debt in the 1880s, with little endowment and not enough state appropriations. Peabody strengthened its finances by selling some of the land grants, thus tripling University income. He also succeeded in having the name officially changed to the University of Illinois in 1885, although he fought the law that allowed for the popular election of University trustees, which passed in 1887. An authoritarian president, Peabody continued to ban fraternities and enforce military drills and compulsory chapel. He also resisted the trend toward the elective system for courses. In the face of student unrest and unpopularity with alumni, the trustees asked for Peabody’s resignation in 1891.

Seeking a prominent successor, the trustees spent three years looking for a man with a national reputation. In the interim, they appointed Thomas J. Burrill (1839–1916) as acting regent. Burrill was a professor of botany and horticulture and a pioneer in the field of plant pathology. In response to student demands, he lifted the ban on fraternities and relaxed military requirements for upper classmen. Burrill also encouraged the development of intercollegiate athletics. He improved relations with the faculty by creating a tenure system and salary classifications, as well as by increasing faculty self-governance. The University also benefited from better federal support. The Hatch Act of 1887 provided needed assistance for agricultural extension, and the Land-Grant College Act of 1890 increased funding by thousands of dollars a year. The State of Illinois increased its biennial appropriations, putting the University on a solid financial foundation.

In 1885, the school changed its name from Illinois Industrial University to the

University of Illinois. (Courtesy of UIC Library of health Sciences)

Andrew Sloan Draper

In 1894, the trustees appointed Andrew Sloan Draper (1848–1913), naming him the first president of the University of Illinois. They had been seeking a nationally known scholar like Woodrow Wilson, but they settled for an administrator. Draper had not attended a university, instead taking a year’s law course before moving into politics in his native state of New York. He served briefly as a judge, then on the Albany school board, before becoming New York State’s superintendent for public instruction from 1886-92. He then headed Cleveland’s schools.

Draper’s grasp of legislative politics served him well in Illinois. His lack of formal education did not prevent him from hiring strong faculty and expanding the University’s offerings, including adding graduate courses, the schools of law, music and library science, and negotiating affiliations with the Chicago-based, for-profit colleges of medicine, dentistry and pharmacy in 1896 and 1897. State appropriations grew substantially, from nearly $300,000 in 1893 to more than $1.1 million 10 years later. The undergraduate population expanded from around 500 to almost 1,500 during Draper’s term.

The growth of the faculty and the strengthening of the college deans, combined with Draper’s authoritarian rule, led to clashes over educational policy. Draper resigned in 1904 and became commissioner of education for New York State. During the 10 years of Draper’s administration, the University of Illinois grew from a small college to a modern university. As historian Winton Solberg wrote, the “foundation had been laid” and it “was poised for takeoff.”

Fred W. Beuttler, Ph.D., ’83 las, served as the associate university historian at UIC from 1998-2005. He currently is the associate dean of Liberal Arts Programs at the Graham School of Continuing Liberal and Professional Studies at the University of Chicago.