Mr. Roundtree

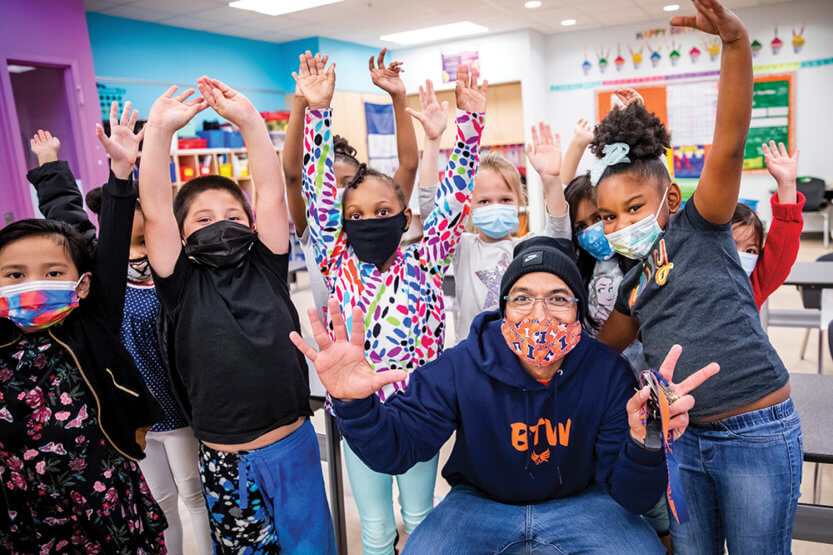

Jaime Roundtree admits he doesn’t dress like a conventional principal. His morning classroom video message doesn’t sound like a typical administrator either. But, Roundtree says if it helps break down barriers and connect him with kids, then his message of believing in yourself and embrace opportunities might just get through. (Image by Fred Zwicky)

Jaime Roundtree admits he doesn’t dress like a conventional principal. His morning classroom video message doesn’t sound like a typical administrator either. But, Roundtree says if it helps break down barriers and connect him with kids, then his message of believing in yourself and embrace opportunities might just get through. (Image by Fred Zwicky) When it comes to the urban schools of America, the name Booker T. Washington is, to be frank, a profile trigger, provoking thoughts of ambitious but crumbling architecture, ancient brick, wavy windows and restrooms that smell of generations of use. Such an elementary school once stood at the corner of Grove and Wright streets in north Champaign, a neighborhood with strong community ties but also gun violence and crime problems. After the building was demolished in 2011, a very different school went up—Booker T. Washington STEM Academy, the district’s showcase for science, technology, engineering and math education. Housed in 60,000 square feet of functional, pleasing areas that flow together to promote learning and community, it’s a singular elementary school, headed by a singular principal, whose name is Jaime Roundtree, ’98 LAS, EDM ’05, EDM ’10.

The building’s formal front entrance is low, behind an angular postmodern portico inlaid with a mural of the Fibonacci sequence. Within, spaces vault to two stories, such as the large lobby/cafeteria where one wall is devoted to a massive graphic of Black icon Washington and his scientific achievements 1856–1940. The lobby doors open on the back of the school, the “real” entrance where parents drop off and retrieve their kids each day. Offices housing secretaries, administrative assistants and the school nurse also are off the lobby, in a suite rimmed with colorful, aspirational college pennants—Yale, Harvard, Wisconsin, Howard, Mississippi State and, of course, Illinois. At the back of the suite is the office that is command central for Roundtree, who became principal here two years ago.

The walls are white. Big windows look out onto the street. A large desk supports books, paperwork and assorted stuff, succumbing neither to the excavation-of-Mesopotamia depths found in some offices nor the weird paper- and book-free minimalism of others. Muhammad Ali challenges all comers from a wall poster. Hung alongside kids’ drawings and motivational messages (Black Teachers/Black Community/Black Families/Black Students MATTER), the poster of Ali is inscribed in gold ink “to Roundtree.” The boxer, activist and Black icon presented it to Roundtree’s dad when the two met on a peace mission to Iraq in 1990. “It reminds me of who my Dad was,” Roundtree says from behind a face mask bearing the words, “No Justice, No Peace.”

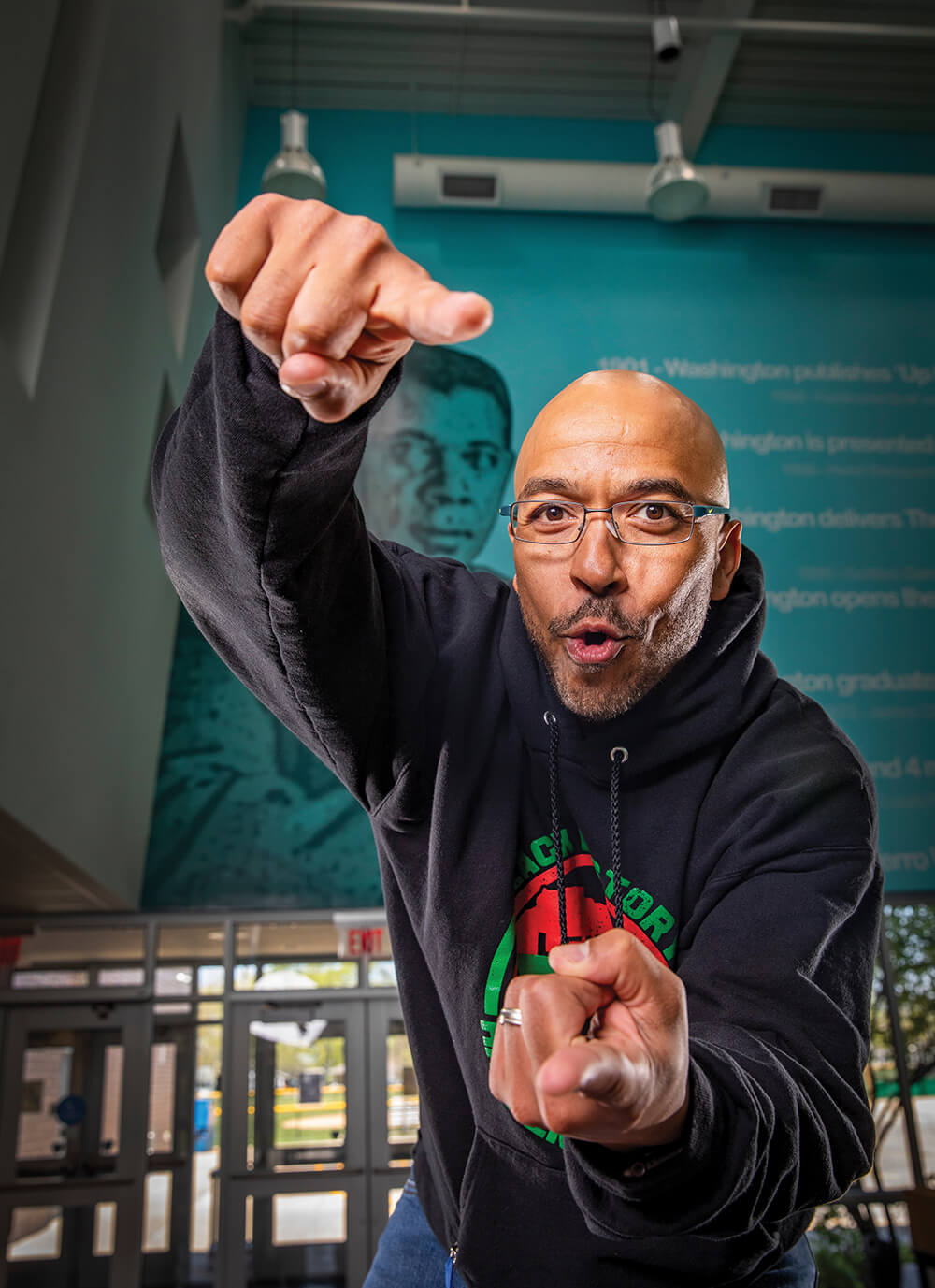

Jaime Roundtree has a level of energy and enthusiasm that many school principals might envy. The one-time leader of the rap group the primemeridian began his career in education as a substitute teacher in Oak Park, Ill. (Image by Fred Zwicky)

Roundtree grew up on Chicago’s West Side. He’ll be the first to say that bad things were going on there, and he’s also the first to defend the “beauty in the slums that I was from.” Perhaps this sense of perspective helped power him past the many pitfalls of Chicago’s mean streets to the University of Illinois, where he took his time earning a history degree—years of study and hustle comprising, in his words, “the very longest undergraduate tour you could ever do.” Meanwhile, tours of another kind began to happen for him. He and a couple of musicians met up and started rapping. They called themselves the primemeridian; they played on campus, they went on the road. They stayed in that groove for years, doing gigs around the country—Jaime Roundtree, aka, “tree,” the lyrics man, a short skinny guy in a big shirt, syncing out the words to the beat as spotlights drown the stage in wild light and the crowd chants back.

I want to put an end to government corruption

I want the working class to own the means of production

Self-determination, not self-destruction

My people of the struggle need no introduction

Today his performances are all for “BT-Dub,” as the school is affectionately known to those who spend a lot of time there. At BT-Dub, Mr. Roundtree gets top billing every day. Masks cover smiles and elbow bumps stand in for high-fives, but the man knows every child’s name. There’s art and entertainment in the video announcements that he records every night and sends out every morning to everyone in the BT-Dub network, from classes in the building to pupils online to support staff. He even plays straight-up shows, like for the school holiday pajama party a couple of years ago—Mr. Roundtree in Santa hat, comfy winter onesie and red running shoes. Kids in pj’s hunkered on the floor of the gym/auditorium, clapping in time to the drum machines, their principal rapping up and down the stage.

Ain’t no party like a Booker T party

And the Booker T party don’t stop

Ain’t no party like a Booker T party

And the Booker T party gonna rock

It’s one gig he would not have imagined back in the days, post-U of I, when he’d tour with the primemeridian until the gig was done and he’d end up back at his mother’s house on the West Side, being, uh, a little broke. She suggested he try substitute teaching over in Oak Park. And, whoa. The rapper turned out to be a teacher. The kids liked Mr. Roundtree. Even more helpful, he liked them. He kept subbing. A long-term interim position opened up when a teacher went on maternity leave. The principal offered it to him. He will never forget her—Felicia Starks Turner. She saw something in him, even when he erred one day and didn’t make it to his classroom full of little kids, uh, exactly on time. She told him he couldn’t do that anymore, and he was never late again. He kept subbing. He started to see a life beyond rapping and gigs and coming back to his mother’s house, broke. He returned to Champaign-Urbana and the U of I, determined to become a straight-up elementary school teacher.

A professor at Illinois—Violet Harris—saw something in him, too. She guided him into a master’s degree program that included teacher certification. “I don’t know if I should thank her or blame her,” he says. He went through the program and signed on for student teaching at Southside Elementary. First-grade teacher Lisa Carney was surprised when the middle-aged white lady whom she had expected—based on the assignment notification and the ambiguous name “Jaime”—turned out to be a handsome young Black man. He got his certification and his master’s degree, and he stayed at Southside, teaching fifth grade for five years. Carney also saw something in Jaime Roundtree. She has since become Lisa Roundtree. They now have five kids.

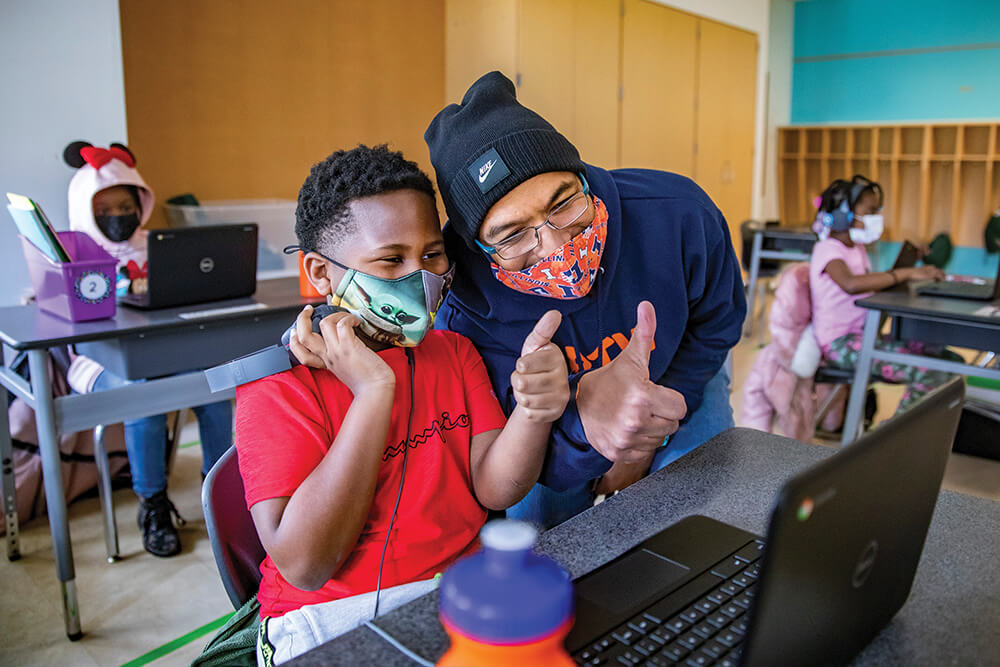

“There should be a space for students to come in here and be who they are, not what we want them to be,” says Roundtree, who became the principal of Booker T. Washington STEM Academy in 2019. (Image by Fred Zwicky)

Lisa Roundtree still teaches at Southside, while her husband moved to posts as assistant principal and principal. A Champaign School District 4 administrator—Susan Zola, EDD ’97—saw something in him. She promoted him to director of elementary teaching and learning for the district. Each upcycle was a leap into new difficulties. How to run a classroom. How to run a school. How to provide cutting-edge curricular materials to teachers. “Being a director was tough, especially my first year,” he says. “But being a principal—oh, my gosh.” Still, he went back to a school, becoming principal of BT-Dub in 2019. Principal means there’s incoming from every direction and dimension. Parents, teachers, administration. The facilities. The rules. The budgets. The mandates. The benchmarks. The goals. The dreams. The kids. The systemic racism.

He sees how the systemic racism of American society breaches the walls of BT-Dub and penetrates the minds of many of the pupils themselves. Black and brown kids. Kids like he was. Kids born into and steeped lifelong in the cruel misunderstanding that they are somehow lesser beings in a rich country that lards its huge opportunities with incredible ruthlessness. Kids who have got it in their genes to feel that they are not important, that they don’t matter. Genes from parents born into those same feelings, and from grandparents, and from generations before those generations, stretching back to slavery.

If you’ve never seen the sun you can’t enjoy it

Never heard the truth, I don’t expect you to voice it

What does a school principal do to combat this? Help them feel better about themselves in as many ways as he can. Get out there in the circle drive off the lobby and greet the kids by name as they arrive. “What’s up, Tanisha? Look at that smile!” Help them see what structure and discipline really mean—like why it’s bad to fight, how fighting doesn’t solve problems, even though sometimes it seems to. Connect with their parents and their community. Know the kids and help the kids know themselves. “There should be a space for students to come in here and be who they are, not what we want them to be,” he says. “We tell them, ‘pull up your pants,’ we tell them, ‘take off your hat,’ we tell them, ‘don’t talk like that, don’t use those words.’ But all their culture is about that.”

“Why go back to what we know wasn’t working? Take risks, take falls, take it slow.”

The building itself is a paradigm for education that flows and collaborates and adapts, sweeping pupils along to engagement and self-realization. Classrooms are flanked by pods of common space where several classes can simultaneously join in big, messy, exciting projects. A bright library beckons young readers with child-height bookshelves and tables. A lab devoted to STEM activities opens onto the school’s outdoor nature exploration areas. Panels and corridor walls sport fresh, startling colors—lilac, orange, gold, aqua, melon, lime-green, plum. Quotes by scientific icons such as Carl Sagan and Isaac Newton adorn the walls. There’s also Archimedes: “Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it and I shall move the world.”

It’s a great layout and atmosphere for learning—though not one designed with social distancing in mind. COVID has changed so much. Those big group projects? On indefinite hold. Classes this spring have been meeting four days a week, as per the district model. Two hours a day in person, 1-3 p.m. About a third of the kids are attending in person. For the other two-thirds, there’s online instruction in the mornings. No onsite art or music—teachers coach those subjects from a distance, working solo at their computers. It’s a mess, but one would never know from a random classroom visit—kids bent carefully over their reading, jumping up to wave as Mr. Roundtree comes through.

BT-Dub knows Mr. Roundtree. And Mr. Roundtree knows BT-Dub. He loves the school. He also sees its system as not working for many of its kids, as a terrible marginalizing trap for minorities. In the standardized testing that is entrenched in that system (as in public education everywhere), only about a third of his fifth-graders are meeting competencies at grade level. He’s been thinking hard about why this is, about the problems of a system that tells kids to do things they don’t understand, that files them in classrooms—“boxes of rows and desks”—according to age and the number of years they’ve been in school. A system that stresses drill and practice, educating some kids, sure, but causing many others to repeat their errors, getting worse and worse at what they do, feeling more and more disaffected with school. A new approach to teaching—that’s what he went to work on a couple of years ago, soon after taking over as principal. He began talking to teachers about changes to curriculum, about progressive scheduling, about replacing grades with more innovative assessment techniques. Some thought his ideas sounded great. Others thought he was crazy. Then COVID hit and blew up everything.

Roundtree believes that COVID-19 has presented an opportunity to reset the paradigm for teaching. For example, he’d like to see one that incorporates both classroom and at-home learning, and allows for greater tailoring of curriculum to individual classrooms. (Image by Fred Zwicky)

I peep the lies, I feed the blind, because I read and write

Beneath the skies, I hear the cries screamin’ freedom fight

We need to fly beyond the speed of light to free the mind

And once the mind’s free, we’ll find the key to see through time

It’s typical of the engaging Mr. Roundtree that he now sees what he calls “an alignment of the stars” beyond the pandemic. When school resumes in the fall, the kids who spent 2020–21 at home will come back with their levels of learning all over the place. Many will be a year behind. Those who had already been a year behind may be two years behind. Some will even be ahead because they found out that they liked to learn at home. So “why go back to what we knew wasn’t working?” he asks. The question is not rhetorical. The potential for change is there. How about, for example, keeping a COVID-inspired model in place, supporting kids to learn at home as well as at school? How about creating more time during school hours for exploration, when, as he puts it, “kids get to be who they are. Show us who they are. And we get to learn with and from them.” As for the teachers, so many of whom have stepped up and proved themselves amid the nightmare demands of elementary education in quarantine—how about supporting them now and helping them to develop and tailor curriculum to meet the needs of their individual classrooms? That’s what he himself did, back as a fifth-grade teacher, before public education policy swung back to basal instruction, with its prescribed learning outcomes and assessments. Here at BT-Dub, the very architecture is built on the concept that pupils and teachers learn together and from each other, including through projects that encourage them to collaborate and develop their talents and strengths. “How do we get back to that?” he asks. “How do we swing the pendulum a little bit?”

And how at the same time to keep moving forward? How to keep giving these kids pride in who they are? There is much to celebrate and commemorate throughout Black History Month in February. And during Women’s History Month in March. But what about commemorating learning every single day? “We’ve got enough knowledge and experience in our building and in this district to think of a different way to do school,” Roundtree says. “Especially for a school filled with predominantly Black students, a school that’s grounded and founded in the Black experience. Learning that experience is valuable whether you’re Black or not.”

When Mr. Roundtree talks, the ideas, the thoughts, the observations, the memories, the concerns, the obsessions come in an enormous rush, unstoppable as the thump and wash of waves on a beach or the driving lyrics of a rap song. He used to go to the beach with his grandfather in the summer. During fall, winter, spring, young Roundtree lived on the West Side of Chicago with his brothers and his sister and his mother, who had her own problems. His father went on social justice missions, like the one with Muhammad Ali, but faded away from his own family, ending up far away, in Detroit. Summers, though, Jaime Roundtree spent with his grandfather on the island of Martha’s Vineyard. This brought him what might be called, in a vast understatement, perspective. He had gang friends, and he saw kids get shot. He also got to go out on the ocean and fish in one of the prettiest spots in North America. He knows, oh he knows, what the kids at BT-Dub are going through. And he also knows there are ways out and places far beyond north Champaign. Ways out for these lovely kids, with so much ahead of them that could be good and so much more that will be tough. Keisha, Tyrone, Marcus, Tanisha, Amina, “Action” Jackson, all the pupils at the school, pupils past, present and future. So many kids, so alive in the moment, so needful of attention, so full of possibility. So glad to see Mr. Roundtree, principal of BT-Dub.

But really ain’t about where you’re from but where you’re at

So we choose to be in a place with harmony right and exact

Lyrics by Jaime Roundtree, 2005; used with permission.