Ingenious: At the quantum level

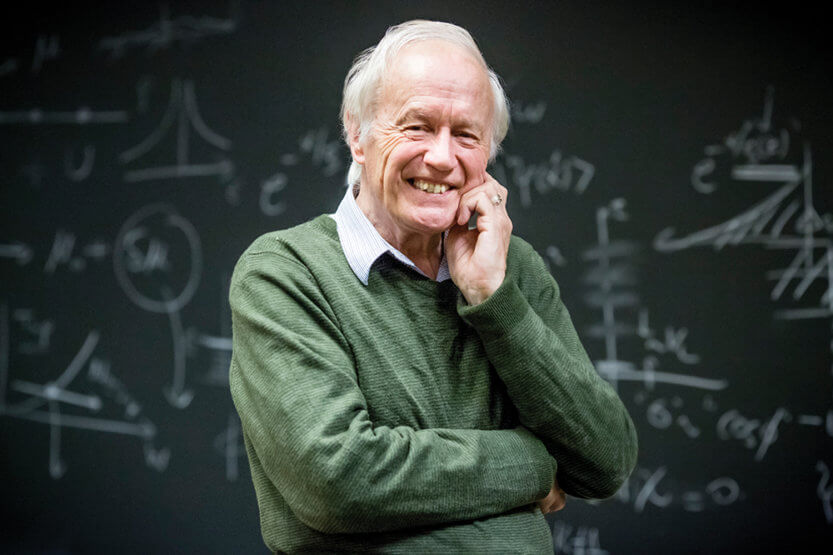

Professor Anthony Leggett’s 2003 Nobel Prize recognized his research into the superfluid properties of isotope helium-3. (Image courtesy of UI Archives)

Professor Anthony Leggett’s 2003 Nobel Prize recognized his research into the superfluid properties of isotope helium-3. (Image courtesy of UI Archives) When University of Illinois physics professor Anthony Leggett was 7 years old, he had a fascination with digging holes in the family garden in Englefield Green on the outskirts of London.

Leggett continued his penchant for digging as a physics researcher, this time at the quantum level, where physical systems display often astonishing properties. His 2003 Nobel Prize in physics recognized his investigation into the superfluid properties of isotope helium-3.

Superfluidity can be observed when certain fluids, typically liquid helium, flow without internal resistance at mind-bogglingly cold temperatures. When Leggett applied for postdoctoral work at the U of I in 1964, he says he had “laughable credentials.” Nevertheless, he was accepted into Professor David Pines’ prestigious physics research group. At Illinois, Leggett made what he considered an exciting discovery about superfluidity, and it became a turning point in his career.

Researchers suspected that helium-3 could become superfluid when it formed pairs of atoms. Leggett compares this unusual pairing to two modern dancers who stay in synch with each other despite being separated by many other dancers between them. Leggett’s previous experiments on helium-3 at Cornell University fit this superfluidity analogy—a hypothesis that was not obvious at the time.

Leggett also contended that the bizarre effects of quantum mechanics could be observed at the “everyday” microscopic level. “But I was met by considerable skepticism,” he says. When a colleague tried to set up an experiment to test that capability, he was told, “You’re wasting the taxpayers’ money. Everyone knows this experiment isn’t going to work.” But in 2000, it did work, proving Leggett’s contention.