The State of the University

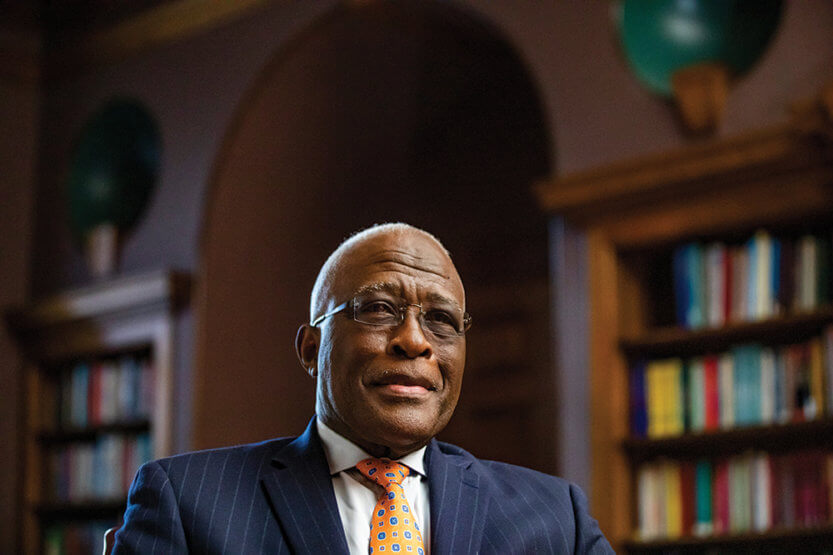

Chancellor Robert J. Jones joined the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

in 2016. Previously,

he served as president of the University at Albany, State University of New York. (Image by Fred Zwicky)

Chancellor Robert J. Jones joined the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

in 2016. Previously,

he served as president of the University at Albany, State University of New York. (Image by Fred Zwicky) IA: In the Spring ’22 issue of Illinois Alumni, we published a cover story on the first graduating class of the Carle Illinois College of Medicine (CIMED). What’s your take on the College?

RJ: It’s a game-changer. I was at a meeting with the deans, and our new dean of the CIMED, Dr. Mark Cohen, was there. I said, “Mark, you’re having a white coat ceremony for the fifth class? Sixty-four students, the largest number we’ve ever admitted at one time. How many applications do you think you had?” We had 3,000 applications for 64 slots! Eighty percent of the students have undergraduate, master’s or Ph.D. degrees in some form of engineering.

Most universities with medical schools have an academic health center with the medical school at its core and other related schools and colleges: nursing, pharmacy, dentistry, public health. We have expertise across every one of these areas—they’re just not sitting in their own colleges.

IA: Do you envision a University-wide model for medical education and research?

RJ: I have charged a visioning committee to determine how we can create a new type of academic health center, where we can get people to work together to find solutions to complex problems. I’ll give you one example. We can discover and test new drugs without having a formal school of pharmacy. We’re already doing this with a number of cancer-related drugs with partners like the Mayo Clinic. Next, we’re going to leverage across our other health-related entities: the Interdisciplinary Health Sciences Institute, the Colleges of Applied Health Sciences and Veterinary Medicine, our Translational Research Center, our Cancer Center and our Jump ARCHES Health Care Engineering Systems Center. We want to integrate across all the health assets that we have at the University in order to have a technology-driven academic health center that, over time, could be just as impactful in improving health and saving lives as the most massive, highly sophisticated clinical research enterprises in this country.

Chancellor Jones led the school’s record-breaking With Illinois fundraising campaign, which is expected to generate $2.75 billion in gifts. (Image by Fred Zwicky)

IA: How has the U of I maintained its position as a research powerhouse? What does Illinois do better than other schools?

RJ: We are the most multidisciplinary university on the planet. In addition to our 15 colleges, we’ve got 10 interdisciplinary institutes that work at the intersectionality of the different academic units. A lot of universities talk about being interdisciplinary, but it’s just talk. It just doesn’t work. Folks don’t get along. They don’t want to work with each other. We have just the opposite here. Interdisciplinary research is the rallying cry. It is our biggest recruitment tool for outstanding faculty. It is why we have been able to get some very large research grants. Outside funding for multidisciplinary research is now in excess of $750 million at this University. For six of the last seven years, we have been ranked the number one institution in the U.S. for the amount of funding we get from the National Science Foundation.

IA: Quantum computing holds the promise of solving ever-increasing complex problems. What’s Illinois doing on this frontier?

RJ: We have partnered with the University of Chicago to leverage our collective strengths and position the state of Illinois to become a leader in quantum computing. Let me say it succinctly: I don’t know what quantum is but I know it’s important. A lot of it defies conventional explanation. Let’s begin with the fact that we use a series of zeroes and ones to do computation. That’s the digital system that most computers and supercomputers are based on. But in the future, we’re going to use the quantum state of matter at the atomic level to do computations, and sensing and modeling at a rate that makes current computational power, even with our supercomputers, look like a horse-and-buggy compared to a Model T Ford. It’s literally a quantum leap.

“Interdisciplinary research is [our] rallying cry. It is our biggest recruitment tool for outstanding faculty.”

IA: Why is quantum computing so important?

RJ: Quantum is a race for the next level of innovation in science and engineering. It will be like the space race, but many times more important. Whatever nation controls quantum computing will dominate the world economically for decades to come. Not only will we be competing against other institutions around the U.S., we will be competing globally, against many other nations that want to be leaders in this area. It’s a really big deal.

IA: Since joining the University, you’ve sought to expand opportunities for qualified students to attend Illinois. Tell us about some of those efforts.

RJ: It has been said that there is no civil right more fundamental than the right to an education. I’ve embraced that ideal all of my life. At the core of my administration and my administrative vision is keeping education accessible and affordable. We will be building on advances we’ve already made, like the Illinois Commitment scholarship program, which provides tuition and fees to incoming freshmen and transfer students who come from families earning $67,100 or less. That program, which has been in place for four years, has been great, but we recognize it as necessary but not sufficient. Now we’re working on Access 2030, a plan with the goal of almost doubling the number of African American and Latinx students we admit to this University.

Chancellor Jones addresses the 6,000-plus graduates who attended the 2022 Commencement. (Image by Fred Zwicky)

IA: In recent years, the U of I has had record enrollments. How are graduation rates holding up?

RJ: Overall, about 85 percent of our students graduate in six years, and the number graduating in four years is the highest among our Big Ten peers. Our graduation rates are also 24 to 25 percent higher than other institutions of public higher education in this state. We now have about 35,000 undergraduate students. As the largest university in the state of Illinois—the largest university, period—we are a massive land-grant, research institution and we do a fantastic job of educating at the undergraduate level. If you look at the University of Illinois System overall, we educate about 51 percent of all undergraduate students in the state.

IA: The rapidly evolving workplace is requiring people to learn and master new skill sets. How is Illinois addressing their ongoing continuing education needs?

RJ: The technology- and human-centric environment in which we live has created a whole new set of job and training opportunities. We have to think about partnerships with business entities around training current and future generations of employees—a paradigm known as lifelong learning. We have to be a leader in providing high-quality education and training to folks who may not be seeking a degree. There has been a fundamental shift in the last two years in the nature of work and the job environment. We’re hearing from CEOs of major companies that 50 percent of their workforce will need to be re-skilled or up-skilled in the next five years and every five years after that. The training needs of business are shaping higher education. Our digital/AI/data analytics society is really changing the nature of work. The types of jobs that exist today didn’t exist two years ago. There will be jobs five years from now that haven’t even been conceived yet. People will go into a profession. Then they will come to Illinois to seek skills tied to their employment. Some of these programs are going to be structured in a way that you can stack them, so that based on training and experience, you could qualify, for example, for a business degree.

“The technology- and human-centric environment in which we live has created a whole new set of job and training opportunities. We have to think about partnerships with business entities around training current and future generations of employees—a paradigm known as lifelong learning.”

IA: Many educational institutions are being challenged to improve their diversity, equity and inclusion. What actions have you taken on that front?

RJ: I made a critical decision within my first few days of becoming chancellor. I was very concerned that this University had never had a senior officer at the level of a vice chancellor in charge of diversity, equity and inclusion. We ran a search and recruited Sean Garrick, who has completely revamped the office—including hiring the first associate vice chancellor for native affairs, Jacki Thompson Rand. That has been a critical hire because we’ve had a legacy at this University for almost 90 years of inappropriate Native American imagery that has been very, very problematic in our community. Jacki is helping us think about how we can link more closely to the tribal communities that used to inhabit this land. We also hired Venetria Patton as the first African American to lead the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, the largest college at the U of I. She’s starting her second year here this fall, and she’s doing a fantastic job.

IA: The University’s achievements in education and research are even more remarkable, given the funding situation you inherited.

RJ: When I was named chancellor, I was still in New York [as president of SUNY University at Albany], and people were saying, “Are you crazy? U of I is broke.” Some $87 million in state funding had been cut. That was a big hit. I arrived at the beginning of the second year of that cut. We never have gotten all of that money back. But we have found ways to move the University forward—financially, programmatically and strategically.

IA: What was the most severe effect of the cut in state funding?

RJ: The biggest impact was reputational. Everybody in higher education knew that the state had imposed a budget cut on us, and our competitors, our so-called peers, came looking to steal some of our best and brightest faculty. That first year, we lost more than twice the number of people we normally would lose to natural attrition. And the financial impact of retaining those we were able to retain was pretty large.

IA: How did you deal with the cuts?

RJ: You can’t be in a situation where your vision, your big strategic plans, can be completely derailed because of a decline in state funding. We implemented a new budget model to help us manage our resources more effectively. And we asked questions. How do we become less dependent upon the state? How do we raise more of our own revenue? How do we drive philanthropy? That’s what led to the $2.25 billion With Illinois campaign.

IA: By all accounts, With Illinois has been an unprecedented success. What are some of the highlights of the campaign?

RJ: We secured the largest gift in the history of the University—a $150 million unrestricted gift from Larry Gies, ’88 BUS. We have named the Gies College of Business in his honor. Over the last 20 years, we’ve received very generous funding from the Grainger Foundation, named for late alumnus William W. Grainger, 1919 ENG. All told, gifts to Illinois from the foundation total about $300 million, including a $100 million contribution in 2019. We have named the Grainger College of Engineering in honor of that generosity. We reached our $2.25 billion goal 18 months ahead of schedule and expect to exceed our goal by $500 million.

The University’s groundbreaking SHIELD saliva test for COVID-19 provided students and others with their results in less than five hours. (Image by Fred Zwicky)

IA: An extraordinary achievement in an extraordinary time. What has it been like to guide the University through the pandemic?

RJ: This has been the most unsettling 27 months of my academic career. There is no manual, no handbook, about how to manage a university in the midst of a pandemic. On March 11, 2020, I did something unthinkable. I sent the students home to study remotely. This was not an easy decision but clearly it was the right decision.

IA: Yet, students returned for the Fall 2020 semester, at a time when many other colleges and universities remained shuttered.

RJ: Doing that safely meant that we had to develop our own testing protocol. Out of that came the SHIELD saliva test, the most amazing, scalable, effective, efficient COVID-19 test in the world. We developed and rolled out Safer Illinois, a smartphone app that linked to folks’ test results and could grant or deny them access to University facilities, according to protocol. It was this digital platform, integrated with some of the best epidemiological modeling in the country by a team of our faculty researchers, that informed Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s decisions about statewide COVID mitigation protocols. So we were able to bring people back in the fall of 2020 and to keep positivity rates extremely low, with no spread from the campus to the community. We felt that this was one of the safest places to be in the state of Illinois, if not the world.

“We developed and rolled out Safer Illinois, a smartphone app that linked to folks’ test results and could grant or deny them access to University facilities, according to protocol.”

IA: What does the future look like in terms of COVID?

RJ: As far as we’re concerned, we’re now in an endemic phase of this thing. And that’s how we’re going to act until the Centers for Disease Control, or some other scientific experts, tell us differently.

IA: Do you feel optimistic that the University will continue to move ahead despite the unprecedented challenges of the pandemic?

RJ: A good indicator of our success came last fall over a 10-day period when I was carrying around these two-and-a-half-foot scissors and cutting more ribbons on buildings than I had ever done in my life. Five key buildings, all funded through philanthropy or our own revenue: the world-class Siebel Center for Design; the Campus Instructional Facility, a new, state-of-the-art teaching facility; a renovated home for Carle Illinois College of Medicine; an expansion of the Sidney Lu Mechanical Engineering Building; and groundbreaking for the new Doris Kelley Christopher Illinois Extension Center. To cut the ribbons on state-of-the-art, innovative, adaptable facilities that are going to help advance the vision of this University going forward—in the middle of a pandemic—was beyond amazing. So, I’m more than just optimistic. I’m downright giddy and excited about the future. And you can quote me on that!