100-Year Remembrance: Ghost Story

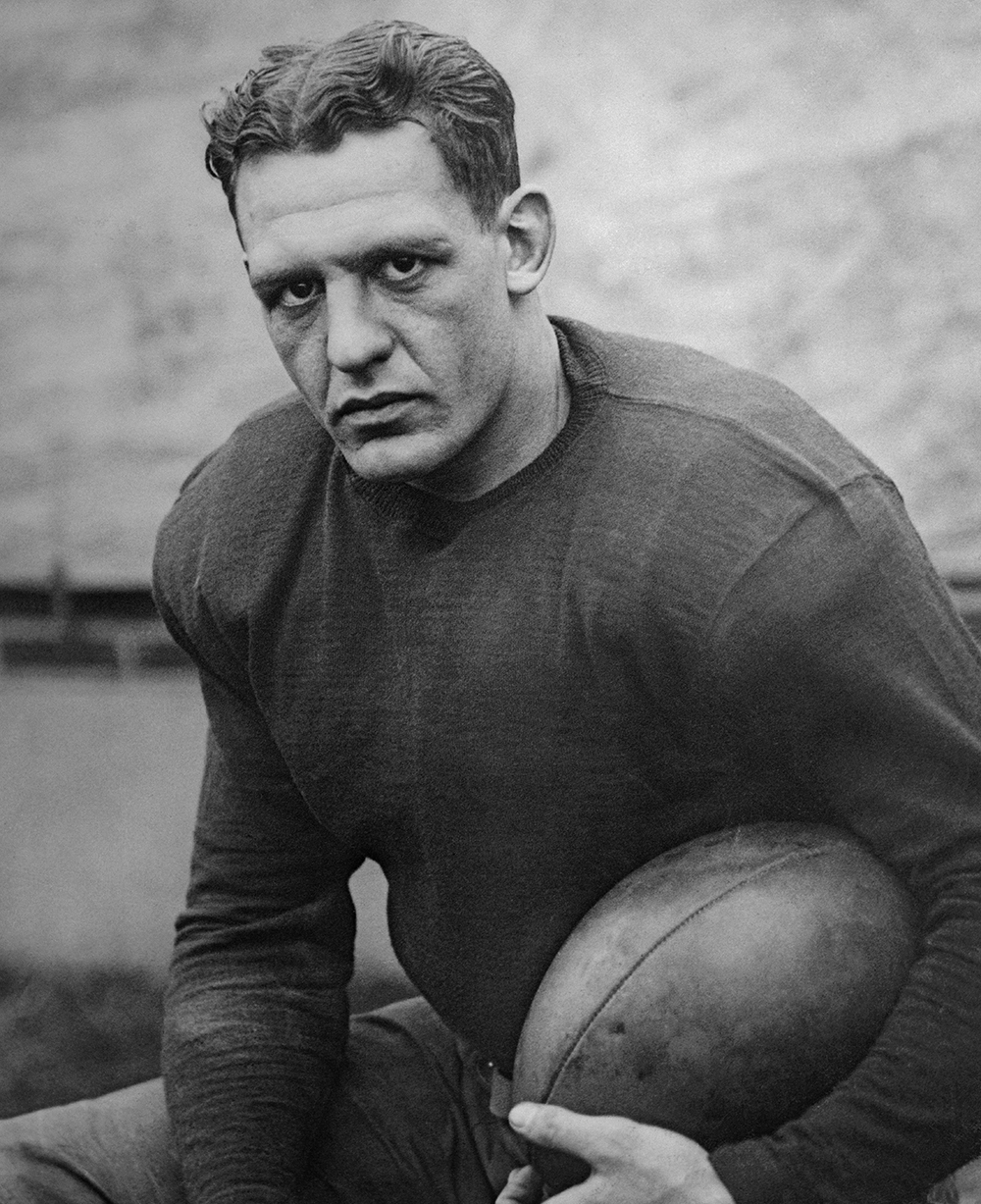

Running back Red Grange for the University of Illinois’ Fighting Illini. (Image courtesy of Bettmann/Getty images)

Memorial Stadium opened in 1923, but its formal dedication came a year later—at the next season’s Homecoming game. The mighty Michigan Wolverines hadn’t lost in two years, but after pregame ceremonies on the sunny afternoon of Oct. 18, 1924, Illinois’ Red Grange had them diving at his shadow as if they were chasing a ghost.

With a crowd of 67,000 roaring for the home team, Grange took the opening kickoff 95 yards for a touchdown. Minutes later, he bolted around left end and raced 67 yards for another score. He added touchdown jaunts of 56 and 45 yards before the first half was over. And Grange wasn’t finished yet. During the second half, he spun and stiff-armed his way to yet another score and threw for a 20-yard touchdown. On defense, he intercepted two Michigan passes.

Illinois’ 39-14 victory made Red Grange a national figure. “Never has any football player gained such prominence,” the New York Times reported, dubbing Grange “the bright bubble of Champaign.” Renowned sportswriter Grantland Rice, who covered the game that day, coined a better nickname in a poem hailing America’s first great football hero:

A streak of fire, a breath of flame

Eluding all who reach and clutch;

A gray ghost thrown into the game

That rival hands may never touch…

Red Grange of Illinois!

Soon, Grange was known as the Galloping Ghost, the star of an Illini team that became a national power, thanks to its uncatchable halfback, a humble young man who arrived on campus in shabby clothes, lugging a cardboard suitcase, wondering if he would ever fit in.

Born in tiny Forksville, Penn., a village of 150 souls named for a fork in the local creek, Harold Edward Grange was the third of four children born to lumber-camp foreman Lyle Grange and his wife, Sophie, who died of typhoid fever when the boy was six years old. Lyle picked up stakes and moved his family to Wheaton, Ill., where he joined the police department. He worked his way up to police chief, putting in 20-hour days while young Harold—known as Red for his copper-

colored hair—cooked meals and looked after his little brother.

The family doctor told them that young Red had a heart murmur. Physical exertion might kill him. “Never get excited,” the doctor said. “And stay out of sports.” But as Red recalled, “I’d sneak out and play anyway.” He spent his summers working on an ice truck, hauling 75- and 100-pound blocks of ice from dawn to dusk, building muscle. A multisport phenom at Wheaton High School, he chose the University of Illinois because “it was the cheapest place to get an education for Illinois residents. There were no athletic scholarships in those days. Besides, every kid in Illinois wanted to play for Coach Zuppke.”

Along with Knute Rockne of Notre Dame and Amos Alonzo Stagg at the University of Chicago, Bob Zuppke defined the role of football coach in the Roaring Twenties. Zuppke had coached at Oak Park High School before leading Illinois to seven Big Ten Titles. He invented the huddle and the “flea-flicker,” a trick play Illinois would unveil in Grange’s senior year. Grange practically worshipped the coach, a deep thinker and widely quoted wit. “Alumni are loyal,” Zuppke liked to say, “as long as a coach wins all his games.”

As a freshman, Grange pledged Zeta Psi. He worried that his better-dressed fraternity brothers would see him as uncouth. No star in the classroom, he flunked rhetoric & composition and earned D’s in accounting and algebra. But he got A’s in gym and soon began making headlines on the football field. In his 21 games for Zuppke’s varsity from 1923 through 1925, he gained more than 2,600 yards and scored 34 touchdowns while joining Babe Ruth and Jack Dempsey as one of America’s most famous athletes.

As Ruth told him, “Kid, I’ll give you a little advice. Don’t believe anything they write

about you, good or bad. And don’t pick up too many checks!”

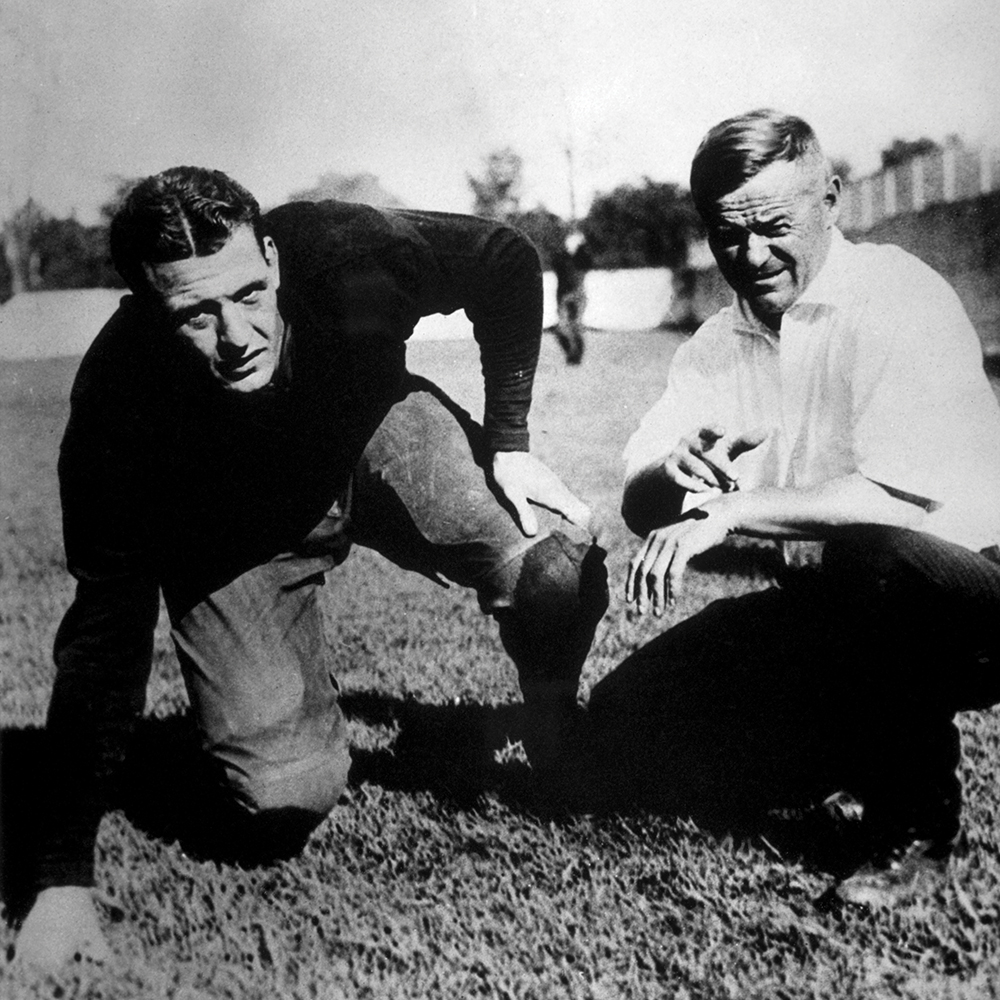

After three glorious seasons in blue and orange, Grange feuded with Zuppke over his decision to turn pro.

In 1925, the National Football League was both new and disreputable. While college men took respectable jobs in the Loop or on Wall Street, roughnecks waged NFL combat for $20 a game. Then a Champaign movie-theater mogul named C.C. Pyle asked, “Red, how would you like to make $100,000, or maybe even a million?” Pyle arranged a contract with the Chicago Bears and a barnstorming tour that would make the 22-year-old Grange a wealthy man.

Zuppke tried to talk him out of it. “Keep away from professionalism. Football isn’t a game to play for money.”

Grange, who was still working summers on an ice truck to pay for his wool socks and football shoes, said, “You take money to coach football. Why shouldn’t I get paid to play?”

Halfback Red Grange and Head Coach Robert (Bob) Zuppke. “I will never have another Grange, but neither will anyone else,” Zuppke once said. “Generations to come will produce their great runners, but only Grange’s name will be immortal.” (Image courtesy of UI Archives)

Less than 24 hours after his last college game, a victory over Ohio State played before 85,500 fans at Ohio Stadium—the largest crowd yet to witness a football game—he signed a contract with the Chicago Bears.

In that moment, pro football became a major sport.

The NFL was small potatoes before Grange joined George Halas’, 18 ENG, club. The Bears had sold only 1,000 tickets to their last game of 1924. Funds were so scarce that the team trainer would wait for the first few customers to buy tickets, then take their cash to a drugstore, where he bought athletic tape and hurried back to tape the players’ wrists and ankles.

Grange instantly put pro football on the map. The Bears drew a sellout crowd of 36,000 to Cubs Park (soon to be renamed Wrigley Field) for his first game. But injuries soon hobbled him. His leather helmet and leather-and-wool pads provided little protection against defenders aiming to exorcize the Galloping Ghost. In 1927, he got clotheslined while reaching for a pass. “When I came down,” he recalled, “I caught my cleats in the sod and hurt my knee. I was on crutches for months and thought I would never play football again.” When he did come back, “I couldn’t cut.” His genius as an open-field runner was a memory. “The injury was the end of me being much of a running back because straight runners are a dime a dozen.”

Even on one good leg, Grange helped lead the Bears to their first NFL championship in 1932. A year later, he made a game-saving tackle as they won again. But he was a shadow of the player he’d been during his college days. After retiring in 1934 at the age of 31, he served as the Bears’ backfield coach, sold insurance and became a beloved broadcaster. In the 1950s, he spent four years as a member of the University of Illinois’ Board of Trustees.

Modest to the end, he quashed a plan to erect a Red Grange statue on campus, calling it “embarrassing. There are so many great football players who played for Illinois, it wouldn’t be fair to single me out.” It was only in 2009, 18 years after his death at the age of 87, that the school unveiled the 12-foot-tall bronze Grange that now dodges phantom tacklers outside Memorial Stadium.

He and Zuppke didn’t speak for years after Grange turned pro. To Red’s relief, they made peace before the coach died in 1957. “I will never have another Grange, but neither will anyone else,” Zuppke once told reporters. “Generations to come will produce their great runners, but only Grange’s name will be immortal.”

Red Grange was a charter member of the College Football Hall of Fame and a charter member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame. When ESPN ranked the “Top 25 Players in College Football History,” he led the list.

Thinking back on his long, eventful life, Grange always returned to his halcyon years in Champaign-Urbana. Here are the first words of his 1954 autobiography, The Red Grange Story:

“It is with a deep sense of gratitude that I dedicate this book to the University of Illinois. Everything good that happened to me in my youth stems from the roots I planted there.”

To read about unsung heroes behind Memorial Stadium’s construction, click here.