In The Time Of PLATO

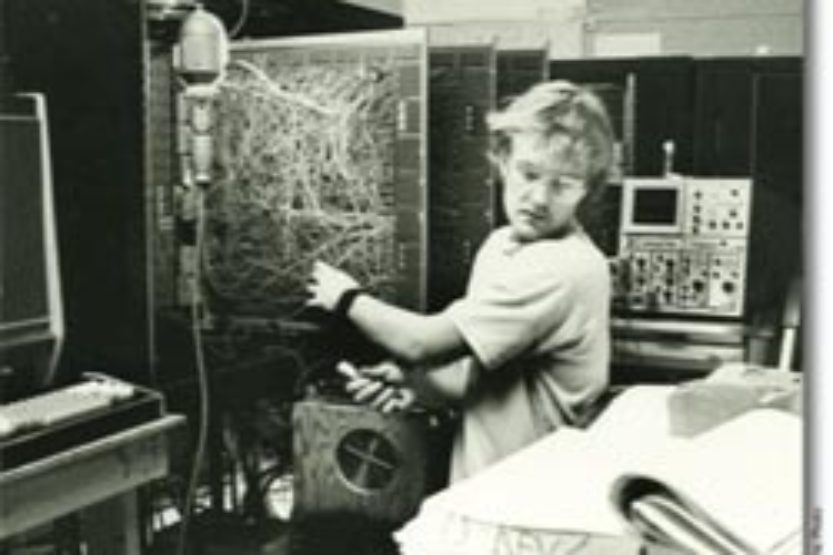

University of Illinois graduate student Lippold Haken wires a computer processor built in 1986 to run PLATO, a networked computer learning system years ahead of its time.

University of Illinois graduate student Lippold Haken wires a computer processor built in 1986 to run PLATO, a networked computer learning system years ahead of its time. They came as inquisitive children. They left as virtuosos, versed in a computer environment decades ahead of its time. Such were the days of PLATO, a networked teaching system launched at the University of Illinois in the ’60s and celebrated at a recent conference in California.

Under the guidance of professors Dan Alpert ’63 and Don Bitzer ’55 ENG, MS ’56 ENG, PHD ’60 ENG, gifted students – many still in high school – pioneered a new way to interact by computer, in an era when data was stored on paper tape and memory cost $2 per bit. Inspired by enormous technical challenges to wild feats of ingenuity, PLATO’s mutable crew of young investigators devised innovations that made possible interactive lessons in which UI students not only learned material but engaged with it and were graded, all on computer. In this endeavor, they prefigured the shape of things to come with touch screens, plasma displays, online chat rooms, multiplayer gaming, cable modems, smart phone lines, instant messaging, blogging and e-newsletters.

“Technology was just on the edge of being able to do some of these things if we used it creatively,” Bitzer recalled of that time. “And we had a laboratory of people that knew how to do creative things.

“We had a lot of young people who didn’t know that there was an answer like ‘you can’t do it.’”

Begun in 1960, more or less at the moment Bitzer hooked a television tube to the Illiac I mainframe on the Urbana campus to see if he could create a computer setup for individualized learning, PLATO stood for “Programmed Logic for Automated Teaching Operations,” an acronym deliberately cultivated to evoke the Greek philosopher and his dialogues. ROGER JOHNSON ’65 ENG, MS ’66 ENG, PHD ’70 ENG, a computer entrepreneur (and a current member of the board of directors of the UI Alumni Association) was a graduate student in the days when PLATO was first evolving. He described its educational paradigm as one “far beyond even what we do today.”

Johnson was on hand for PLATO@50, a conference celebrating the system’s golden anniversary, held in early June at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, Calif. So was Ray Ozzie ’79 ENG. Now chief software architect for Microsoft, Ozzie reminisced to conference-goers about the “friendly orange glow” that drew him as a UI undergraduate into the incredible 24/7 computing world of the Computer-based Education Research Laboratory (CERL), where PLATO was housed. “So many people flunked out of school because of passion about what we were doing,” Ozzie told the capacity crowd of PLATO alumni and executives and researchers from the surrounding computer industry of Silicon Valley. Ozzie’s own work with PLATO would evolve into Lotus Notes, software that won him status as a major player in the industry.

Microsoft was among the sponsors of the two-day showcase of hardware and memories, to which “there was an outpouring of response,” according to C.K. Gunsalus ’78 LAS, JD ’84 LAW, a UI administrator who helped organize the event. Gunsalus herself was one of PLATO’s happy children of the future, going to work for Bitzer while a student at University Laboratory High School (“Uni”) and staying on for more than a decade. Working at PLATO, she said, “changed almost everybody in really profound and important ways. … There was a feeling of believing in what you do and knowing it will make a difference that’s addictive.”

Lippold Haken ’82 ENG, MS ’84 ENG, PHD ’90 ENG, now an electrical engineering faculty member at Illinois, was another fearless young mid-’70s innovator, enticed from teenage responsibilities at Uni to the cutting-edge gaming and music at CERL, which was located on the UI engineering campus in a former coal-burning power plant that dated back to 1912.

“On the weekends, I got in the habit of finding open windows and climbing in,” confessed Haken (who went on to invent the Continuum Fingerboard, a computerized synthesizer instrument now in use by such Hollywood studios as Lucasfilms).

As project mentor, Bitzer handled such obsessions shrewdly. With computer time highly sought-after and monitored around the clock, the students “thought I would squash games,” he said. “But I didn’t. I thought it was probably not a bad thing to have going as long as it didn’t interfere with the education. So we blanked the games during the peak hours of education and locked ’em out. And then we’d bring ’em back in again at night and on weekends.

“People work very hard when they work on things that they believe in.”

For Haken – at least in retrospect – PLATO’s true virtue was in being “so great, so patient” a teacher – one literally incapable of giving up. “If you got it wrong for the whole week, it would keep working at it,” Haken said of the networked tutorials. And for gifted students, PLATO made it a pleasure to “work at one’s own pace.” Moreover, by individualizing instruction on the computer, PLATO freed up classroom time for professors to cover more advanced material and encourage discussions.

PLATO innovations ranged from online tutorials and multiplayer games to blogs and emoticons. From left: A plasma touch screen enables interactive learning; a screen close-up shows a biology lesson about gene inheritance in fruit flies; alumni Don Bitzer, right, and Ray Ozzie recall the allure of PLATO’s “friendly orange glow” for a capacity crowd at a recent conference in Silicon Valley.

The software that supported such coursework was developed by Paul Tenczar ’63 LAS, MS ’69 LAS. Then a graduate student in life sciences, he created a simple language for writing questions and an answer-judging scheme that enabled the computer to grade student work. Within three years, Tenczar said, 3,000 lessons had been developed by UI professors across the disciplines, from physics, biology and chemistry to modern languages and even Latin and the classics (taught by UI legend Dick Scanlon). Custom graphics, emoticons and animations were among the innovations available.

“The courseware,” Tenczar recalled, “was utterly stupendous for its time.”

Having attracted major funding from the National Science Foundation, PLATO grew via phone lines and television microwaves into a network that, by the mid-’70s, reached out of the UI campus into the surrounding community and around the country and the world. Terminals, which communicated with the mainframe at Illinois, featured touch-screen plasma displays and accommodated audio discs and microfiche for use in instruction. Commercialized by Control Data Corp., PLATO eventually produced 10,000 hours of coursework in areas from language and science to training for airplane pilots, nuclear power plant operators and securities dealers. When striking air traffic controllers were fired by President Reagan in 1981, the Federal Aviation Administration turned to PLATO to train the insurgent replacements.

What PLATO, in all the collective foresight of its youth and barrier-shattering paradigms, could not surmount, in the end, was the advent of the microcomputer. Developed to run on mainframes, the online learning system peaked in the ’80s, then slowly faded, not adapting in time to catch the big PC wave that transformed computing – and human life – forever. The system still endures in NovaNET courseware for high school and adult learners and PLATO Learning, a company that provides teaching resources for K-12 and higher education.

“We were riding this crest of technology, and at the same time we had demonstrated the ability to build new things that didn’t exist.” Bitzer recalled. “Those worked together.”

And in its heyday, the system anticipated the “cloud” of today’s computing environment, by pioneering networked education, while giving clever young people a whole new way to share their lives – online.

Editor’s note: PLATO@50 proceedings are archived online,”The Friendly Orange Glow,” a history of PLATO by Brian Dear, is scheduled to be published later this year; for more on this exhaustive work, visit www.friendlyorangeglow.com.