A Long, Hot Summer

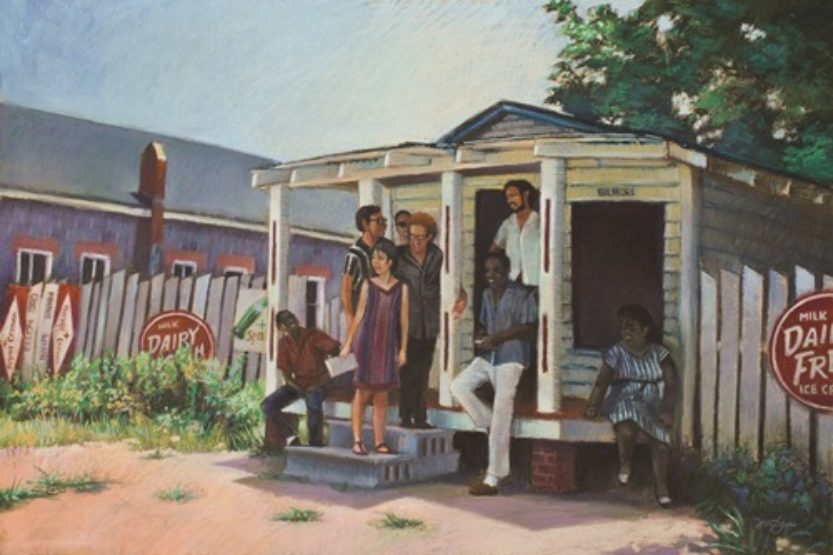

Author Ralph Tyler (in black-and-white striped shirt) stands on the porch of the Illini Alabama Project office next to fellow project members in this rendering by Mark Braught.

Author Ralph Tyler (in black-and-white striped shirt) stands on the porch of the Illini Alabama Project office next to fellow project members in this rendering by Mark Braught. Editor’s note: The Civil Rights and Voting Rights acts, passed by the U.S. Congress in 1964 and 1965, respectively, were landmark pieces of legislation that declared racial segregation and discrimination unlawful. At the University of Illinois, students responded to the massive social changes of the ’60s in various ways, including the formation of the Illini Alabama Project, a registered student organization with 19 inaugural members, whose stated purpose was “to sponsor summer volunteer projects in the area of voter registration, political education and community organization.” In a June 4, 1966, Daily Illini story, student writer Rick Harper ’66 LAS recalled his hopes, frustrations and constant fear while working on the Illini Alabama Project in Greene County the previous summer and stated his intent to return. “I also remember,” he writes, ‘“that we had some good times, and that a change needs to come.” That summer, a young UI student named Ralph Tyler joined the Illini Alabama initiative. This is his memoir.

In 1966, I was 19 years old and had just finished my freshman year at the University of Illinois. The experience of that summer 46 years ago was too important to my development for me not to retain vivid memories. I remember the satisfaction of being with a group of people who worked together in common purpose on something which mattered; I remember times when I feared for my personal safety; I remember the deep pain and sorrow of a fellow worker’s accidental drowning and his tear-filled funeral; and I remember the dust and heat of July and August in rural Alabama.

I knew that student activists from other universities had assisted desegregation efforts in the South, and I decided that was what I was going to do. I believed then and I believe now that you try to find ways you can make a difference. At first I applied directly to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, but when I found out about the Illini Alabama Project workers via their table in the Illini Union, I went with them.

Limited resources, rudimentary conditions

More than 80 percent of Greene County’s residents then were African-Americans (a term not yet in use), few of whom were registered to vote and none of whom held public office. The level of African-American poverty and deprivation in the county was extreme. As my co-worker, Rick Harper, wrote in The Daily Illini, their “condition is only hinted at by the fact that median annual family income for Negroes is still less than $1,000” ($7,110 in today’s dollars).

Segregation was practiced aggressively in Greene County. The minority of white citizens controlled all of the institutions of power and had no interest in sharing power or opportunity with the African-American majority. The condition of the streets in Greene County graphically captured the disparity between the races: In the white sections, the streets were paved; in the African-American parts, virtually all were unpaved and sometimes deeply rutted.

The three University of Illinois students who worked in Greene County were Harper, Bob Felber ’67 LAS and I. Our office was a one-room building located at 317 Greensboro Road, Eutaw, Ala., and had a desk, a couple of folding chairs, a pay telephone on the back wall, a hand-cranked mimeograph machine and Bob’s sleeping bag and record player. Bob slept on the office floor, while Rick and I slept in a spare room in a house a short walk away.

Saying that we “worked” in Greene County does not mean that we were paid. Rick had done some fundraising on campus prior to departing for Greene County, and each of us had brought a little money. We used our limited resources to pay for food, office supplies and gas for the much-used Chevrolet which Bob drove to Alabama and which we used to travel throughout the county. After we exhausted our funds, friends in Illinois, including my aunt, Priscilla Tyler, then a professor in the UI Department of English and College of Education, provided additional financial support. Aunt Priscilla always accepted my collect calls. During one such call, she agreed immediately to wire money so we could purchase a whole pig for the approaching Greene County “Roots Day” barbecue, an annual community event.

Our daily work involved going door-to-door, i.e., sharecropper shack to sharecropper shack. I found their living conditions to be very rudimentary, with uninsulated buildings, few belongings, poor clothing and poorer nutrition. While some people certainly were fearful of taking steps that might evict them, others were amazingly brave. Their reception of us was generally positive as we organized sharecroppers, talked to people about registering to vote, accompanied them to registration and spoke to students and their parents about having the courage to integrate the still all-white Greene County High School that fall.

Our communication strategy also involved newsletters and notices, all of which we wrote, produced and distributed, starting early on Sunday mornings at churches around the county. These fliers announced upcoming “mass meetings,” held in the evenings in various churches, where everyone sat in the plain wooden pews, and people, particularly the women, tried to cool themselves with hand fans. The speakers, many of whom were local ministers, would talk about what was going on in the “movement,” plans for future actions, how much remained to be done and the need to get more people involved. In between passing out the leaflets and attending the night-time meetings, we’d drive to the county’s far south end and cool off by swimming in the warm and murky water of an abandoned gravel pit.

Boycott, jail time and vindication

One Saturday morning in July, Bob, I and Libbie Kirkland, a local African-American teenager who frequently participated in our activities, were on the sidewalks of Eutaw’s shopping district, passing out fliers urging people not to patronize the local stores that refused to hire African-Americans and to shop instead where African-Americans had jobs. This activity upset both merchants and local law enforcement authorities and led to our arrest. As Greene County Sheriff Bill Lee escorted us to a police car, he asked whether we had read Alabama’s anti-boycott law. If we had replied to his question, which we did not, the answer would have been “no.” Lee assured us that he never acted without first becoming fully versed in the relevant law and suggested we would be well-advised to follow his example.

Bob and I were put in separate cells in the jail’s relatively upscale “white section,” and Libbie was taken to the “colored section.” Segregating us by race seemed ironic, given what we were doing in Greene County and the conduct which triggered our arrest, but our jailers didn’t seem to appreciate it.

Once we were released from our brief stint in jail, we learned that Sheriff Lee had a point. Alabama law made it a misdemeanor to circulate “any notice of boycott … [or] publishing or declaring that a boycott or ban exists or has existed or is contemplated against any person, firm, corporation, or association of persons doing a lawful business.” While law school was still several years away, I was able to discern that we had done what the law prohibited.

We had the great good fortune to be represented by a fine lawyer, Donald A. Jelinek, who had an office in Selma, Ala., where he did civil rights work, including representing civil rights workers. T.H. Boggs, the local district attorney, dismissed the charges against us after Jelinek commenced a federal lawsuit challenging Alabama’s anti-boycott law on First Amendment grounds guaranteeing free speech. When all the legal proceedings were concluded in the case Kirkland v. Wallace 403 F. 2d 413 (5th Cir. 1968), we faced no charges, and the law was declared unconstitutional.

Later that summer we used Jelinek’s services for a case to be brought on behalf of African-American farmers in Greene County and elsewhere in Alabama. Filed in federal court in Washington, D.C., against the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the case challenged the system of elections used to select members for the local bodies that determined cotton crop allotments. The election system was rigged to prevent participation by African-Americans, which, of course, meant that they fared poorly in the allotments they received.

I drove a borrowed VW van to transport African-American farmers from Greene County to D.C. for the preliminary injunction hearing in the case. We drove through the night, both there and back. After stopping to eat in Virginia, my friends told me that was their first experience of dining in a restaurant with white people. While in Washington, we stayed in the Georgetown home of two prominent lawyers, Jean and Edgar Cahn.

Our trip to Washington was a success. The court issued a preliminary injunction, ordering that the elections in Alabama be postponed. That allowed for more time to encourage candidates to run, increasing the likelihood of a fairer and more racially inclusive process.

Legacy of the Illini Alabama Project

Every summer vacation comes to an end. When we left Greene County, Rick went to graduate school at the University of Chicago, and Bob and I returned to Champaign. I moved into a room in Townsend Hall for my sophomore year.

What, then, is the legacy of the Illini Alabama Project? As far as I know, it did not last beyond 1966, and that was as it should be. The role of white people in the civil rights movement was somewhat fraught from the outset, and by 1966 that issue had become a divisive distraction. There was also the undeniable fact that racial separation and discrimination were (and are) national, not regional, afflictions, thus making the idea of “going to the South,” rather than to, say, Chicago, Cleveland or Detroit, an anachronism at best.

While the legal framework of segregation has been dismantled, barriers and disparities between the races remain enormous. None of this diminishes the fact that the Illini Alabama Project had its place and served a worthy purpose. I have no doubt that all those who participated in and supported the project in 1965 and 1966 did some good and that each learned from the experience. One cannot ask more from a college activity.

I hope that students currently on the three campuses of the University of Illinois are finding worthwhile ways to become engaged, to learn and to test their evolving beliefs against the reality of the world. One of the great luxuries of going to college is that it is a time set aside to prepare for the lifetime to follow, one which I hope includes fulfilling work to make the world a more peaceful and more equitable place.

Tyler ’69 LAS, a partner in the law firm of Venable LLP, works in the firm’s offices in Baltimore and Washington, D.C. He is the former deputy attorney general of Maryland, Baltimore city solicitor and chief counsel of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.