Space Booster Marc Lapides

Illinois alumnus Marc Lapides serves as vice president, chief marketing and development officer, for Adler Planetarium in Chicago. (Photo by Courtesy of Callie Lipkin)

Illinois alumnus Marc Lapides serves as vice president, chief marketing and development officer, for Adler Planetarium in Chicago. (Photo by Courtesy of Callie Lipkin) It’s a stormy November night, and ferocious winds lash the plate glass windows of Café Galileo’s, but hundreds of people have braved the elements to enjoy Members Night at Chicago’s Adler Planetarium. There’s a new exhibit, Mission Moon, focused around astronaut Capt. James A. Lovell Jr., who lives in Lake Forest, Ill. The live entertainment is an Astronomy Slam featuring Adler’s brainy scientists who will vie for top honors with speeches such as “Asteroids May Kill Us All” and “Space Is Really Freaking Big.” If this seems a far cry from earlier chestnuts such as “Mysteries of the Universe,” give plenty of credit to the Adler’s creative marketing chief, the high-energy Marc Lapides, ’91 LAS, who’s spearheading the planetarium’s new mission to make space relevant and fun.

Lapides is especially busy tonight, seeming to defy the laws of physics as he pops up all over the building. “I absolutely abhor when visitors have to stand in line. Giving directions isn’t always easy in a round building,” he says at the front entrance, pointing out stairs to two sets of visitors. A moment later, Lapides is bounding up the stairs himself for the Astronomy Slam and confessing: “It’s a great chance for me to pick up some space facts.”

Lapides is new to space. Before he was appointed Adler’s head of marketing and then development, he had spent much of his professional life working at the Leo Burnett advertising agency, launching and running his own cooking school, and, most recently, heading up marketing at Cosi, a fast-casual food chain.

“It’s a change from Cosi,” Lapides admits, “and when I interviewed [at Adler], I made it clear I was not an astronomer. I did not take astronomy in college. But as a marketer, my job is to talk to consumers who don’t understand the topic. I translate what astronomers talk about into language people understand and get excited about.”

CRAFTY AND SCRAPPY

Fewer and fewer people were getting excited when Lapides arrived in Spring 2014. The Adler was never in crisis mode, but research showed that too many people were puzzled by the complexities of astronomy. Advertising, too, seemed to be on the wrong track, relying on a high-volume, low-impact strategy, Lapides says.

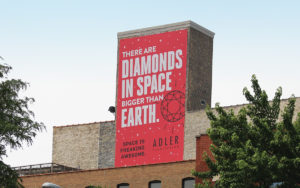

Marc Lapides, vice president, chief marketing and development officer, has brought an edginess to Adler Planetarium’s marketing. The “Space is Freaking Awesome” campaign uses multiple touch points, including social media, to reach targeted audiences such as families and tourists. (Photo courtesy of Adler Planetarium)

“What I call ‘wallpaper,’” he explains. “Lots of taxi toppers and bus sides. When there’s too much around, you tune it out.” To get more attention, Lapides switched to TV advertising, a few big billboards and a major push on Facebook. He also hired an email marketing manager. “We try to use tools that are most efficient in driving [attendance] because we don’t have that much money,” he says. “I would love to have the budgets my neighbors do. We have to be crafty and a little scrappy.”

By his neighbors, Lapides is referring to the 18-museum consortium that includes the Field Museum, Shedd Aquarium, the Museum of Science and Industry, the Art Institute and Lincoln Park Zoo. Most of them have budgets that dwarf Adler’s. But this year, at least in partial response to Lapides’ efforts, Adler tops the go-to culture list in attendance growth. “It’s my favorite statistic,” he says. “We’re up higher than any other museum. It’s not even close. We’re at 21 percent. The next closest is 15 percent, and the average is 8 percent.”

Dr. Michelle Larson, president and CEO of the planetarium since 2012, and the person who hired Lapides to boost the Adler profile, couldn’t be happier. “He has tremendous energy and enthusiasm,” Larson says. “He’s done a great job capturing what we’re about so that people will relate to it. For the first time, we have a presence on social media. He made a very compelling case that [commercial] practices can apply to non-profit cultural content—Marc made that happen.”

Some of the heightened interest is likely due to space itself and headline-generating discoveries—unlike the less than startling news from the museum a few hundred yards west. “The Mayan Ruins will always be the Mayan Ruins,” Lapides says. “The Incas aren’t getting any more interesting than they ever were.” But Adler benefitted from those eye-popping close-ups of Pluto on the front page of every national newspaper, not to mention a rare red lunar eclipse in September, which drew several thousand visitors to the spit of land that is home to the planetarium.

Lapides honed his advertising and marketing skills as a vice president at Leo Burnett, one of the world’s largest advertising agencies. “At the time, Burnett was the advertising job you wanted,” he says. “It was a great place to learn how to grow a brand and protect it.” (Photo by Callie Lipkin)

It’s probable, too, that Adler’s attendance jump is the result of a new initiative to bring space into the community. It all started, says Lapides, when Larson was being interviewed for the CEO job by a trustee in the Aon building. “He walked her over to the window and said, ‘See that? It’s Lake Michigan.’ Then he pointed about a mile away, west, to what were obviously lower-income communities and asked, ‘How are you going to get kids who’ve never even seen the lake to the planetarium?’ What Michelle figured out was we’re not going to get them here—we’re going to go to them.”

A big part of the subsequent plan that Lapides helped promote is a new program called ’Scopes in the City, in which Adler astronomers travel into neighborhoods and set up telescopes. “When you look through a telescope, you can actually see the rings of Saturn,” he says. “I didn’t know that. I thought I was looking at a star. Other people have the same reaction. When they see Saturn for the first time, they want to see more space!”

The goal is not just to drive visitors to Adler—it’s to excite a nation of scientists. “Space is at the front door,” Lapides says. “We talk about space and that’s what brings everyone in. But our underlying goal, what we’re really trying to do, is get kids and teens interested in STEM education.” STEM—Science, Technology, Engineering, Math—figures largely into both Larson’s and Lapides’ sense of a mission at Adler. “It’s a national necessity to have our kids big on STEM education,” Lapides says. “It’s essential for our economic security that kids, whether from low- or high-income [families], get educated in STEM. Science is the backbone of our future and, for me, [that mission] was the most interesting thing about coming to work here.”

GRANDMOTHER’S INFLUENCE

Science was never a consuming passion of Lapides, not even when he arrived in Champaign, Ill., in 1986. He had picked Illinois, in part, because he didn’t know what he wanted to do, and a big school seemed to offer more options. But when Lapides visited the campus, it was love at first sight: “There were tons of students out there on the lawns, studying and throwing Frisbees. The Quad was packed, and I said, ‘This is where I want to go!’” It didn’t hurt that it was a great academic school, he adds, and had a football team that had just been to the Rose Bowl.

Adler guests get hands-on at an event in the Our Solar System Gallery. (Photo courtesy of Adler Planetarium)

Lapides grew up in a small New Jersey town where his father made his living with a chain of auto tire stores, a company started by his grandfather. It was his grandmother, however, who played the biggest role in his chosen career. “She owned her own business and always told me, ‘you need to be something like a doctor or a lawyer so no one can ever fire you,’” Lapides says. He settled on nutrition, a major field of study at Illinois. “It’s close enough,” he told his grandmother. “If I go on to become a doctor, I’ll have my pre-med training.” What changed his mind was one of the nutrition prerequisites, Chem 101. “That’s when I decided, ‘I’m not going to be a nutrition major,’” Lapides recalls. “Chemistry wasn’t my thing. I’d taken a communications class and loved it, so I switched to communications. Eventually, Grandma was OK with advertising.”

After a brief detour at the White House, where he drafted presidential memos, Lapides landed a plum job at Leo Burnett. “At the time,” he says, “Burnett was the advertising job you wanted; it was a fantastic place to learn advertising and marketing. Name any major icon in advertising—the Pillsbury Dough Boy, the Jolly Green Giant, Tony the Tiger, the Marlboro Man—and chances were 50/50 Burnett had something to do with it. It was a great place to learn how to grow a brand and protect it.”

As a Leo Burnett vice president, Lapides worked on Coca-Cola, among numerous high-profile accounts, but after nine years, he got the restless itch. “Everybody in advertising wants to do something else,” he says with a laugh. Lapides had always liked cooking, so he enrolled in night classes at the Cooking and Hospitality Institute of Chicago, but was traveling so much he never made it to class. The 9/11 terrorist attacks changed his priorities. “I thought, ‘You know what? I’m going to do what I like!’” he says. “So like the 200 other career-changers, I decided I wanted to open a restaurant.”

He picked up cooking classes again, but found himself irked at the new school because everyone sat on stools while the teacher cooked. “The only difference between that and the Food Network was maybe it smelled better,” Lapides says. “You never learned anything. Why not a hands-on school where students actually got to cut vegetables and roll out dough?” The result was Northshore Cookery, which Lapides opened in Highland Park, Ill., and ran for six years before deciding enough was enough. “What I finally realized was I liked marketing better than I liked cooking,” he says. “People talk about how everyone wants to be an entrepreneur. The problem is, it isn’t a job description. An auto body shop is different than an accounting firm, which is different than a restaurant. I was an entrepreneur, but I picked the wrong business.”

So Lapides packed up his knives and took a bunch of jobs where he specialized in digital marketing before landing at Cosi. That skill in social media was a prime asset that led Larson to choose him for Adler, though it also was Lapides’ embrace of a more daring advertising strategy for the planetarium. To that end, Lapides tapped some of Chicago’s top ad agencies to pitch for the new campaign, a competition that finally went to Downtown Partners, which won the account with the tagline, “Space is Freaking Awesome.”

“It was brave of him to embrace that idea, which was kind of bold, especially for a planetarium,” says Brenda Donahue, who heads up the Adler account for Downtown Partners. “He’s a very unique client. I’ve had clients who push back or want to change an idea, but Marc finds ways to make it more relevant. He’s really passionate and a fun person to work with.”

The Mission Moon exhibit includes the Moon Wall, which incorporates data being collected from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. The LRO has been making discoveries since 2009. (Photo courtesy of Adler Planetarium)

SCIENCE SOMMELIERS

The agency’s “Awesome” campaign is clearly aimed at a younger generation, though Lapides is quick to note that Adler doesn’t define visitors in terms of demographics, preferring instead a “psychographic,” which he terms “‘the curious’—anyone from 2 to 92.” But boosting STEM education has remained a major mission at Adler, and teens were the particular focus of an early December 2015 meeting in which Lapides and key staff sat down to expand on Adler’s “science sommeliers.” This is a group of teen interns who circulated among 650 guests at the Celestial Ball in September and offered a menu of experiments they would demonstrate tableside, like guessing how much salt it took to float an egg in water. The idea was to expand the program with brochures and cards to reach out to donors and trustees.

“We want to send them a thank-you gift,” Lapides explained at the meeting, “but it’s also a way to show how teens get involved in the Adler. We don’t promote teens enough.”

Coincidentally, that same day in December, Adler issued a press release announcing it had counted its 500,000th visitor, topping a 22-year-old record with one month still to go in 2015. The news, along with details of a revamped website, prompted a major story in the Chicago Tribune in which Lapides generously credited the entire staff for the good news.

“It’s the confluence of a lot of hard work from everyone around here,” he told the Tribune. “It’s a real testament to the new management team and a renewed spirit. I’m thrilled.”