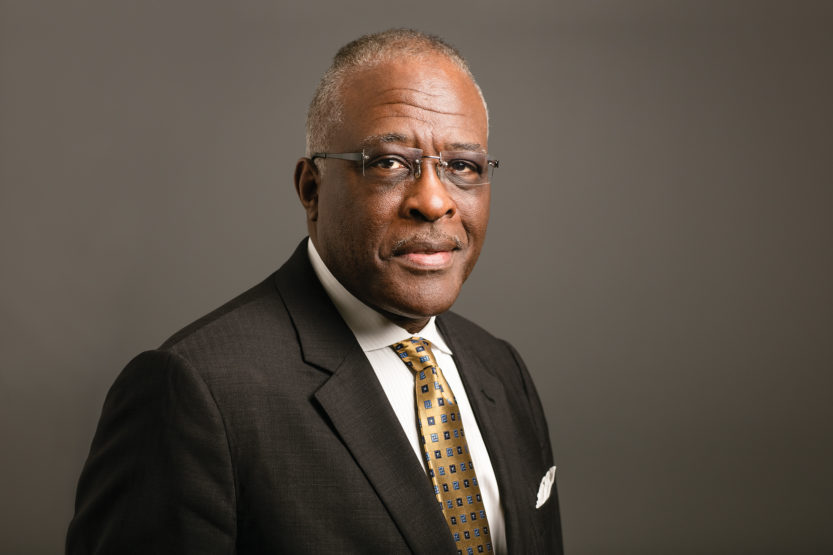

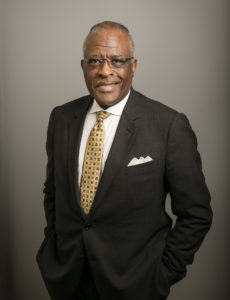

Ideal leader

“The University of Illinois is one of the most highly ranked and outstanding land-grant institutions in the country,” says Chancellor-Elect Robert J. Jones.

“The University of Illinois is one of the most highly ranked and outstanding land-grant institutions in the country,” says Chancellor-Elect Robert J. Jones. “I was,” he begins, with the time-honored nonchalance of an ace storyteller, “sitting around in the lab [at the University of Minnesota], minding my own business.” Then came the phone call—one that would change his life.

It was the vice president of student affairs, Jones recalls. “‘Robert,’ he said to me, ‘the president wants to send you to South Africa.’

“And I asked, ‘What the hell did I do?’”

Jones’ laughter fills the tiny room off Green Street where he’s meeting for an interview with Illinois Alumni—one item among many on a fast-paced to-do list on a hot day in August some seven weeks before he becomes Chancellor of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Distinguished, handsome and charismatic, he is, according to University of Illinois System President Tim Killeen, “going to fit in beautifully.”

“Coming out of the South,” Jones says, “I knew enough about South Africa to say, ‘Wait a minute—I must have done something really wrong.’” Then he laughs again.

The call came during the winter of 1984, when South Africa was in its 46th year of apartheid. What then University of Minnesota President C. Peter Magrath wanted Jones to do was to go interview young men and women of color for a South African government program that would allow them to earn degrees at U.S. universities. That summer—and several subsequent summers—found Jones in Johannesburg, where he got to know the program’s founder, Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

The assignment had ties—deeper perhaps than Magrath knew—to Jones’ own life, beginning as an African American child in the segregated South of the 1950s and ’60s. Not that Jones is wont to dramatize the connection. “As a child, you have a very narrow view of the world,” he points out. “I didn’t think that my life was any better or any worse than anybody else’s in the community.” Notwithstanding, that community was one of sharecroppers who farmed cotton and peanuts, splitting the annual take for crops with the landowners—a tough living, made precarious by weather, pests, unpredictable commodity prices, disease and injury. Jones’ father boosted the family finances by raising pigs, and his mother worked as a domestic. They also improved the outlook for their children in an additional way.

“It was standard practice for kids to miss school in order to pick cotton, a crop that was normally harvested after school would start,” Jones says. “My parents made it very clear that education was important and that we would not stay out of school to finish harvesting cotton.

“But as that school bus rode through the plantation between 3 and 3:30 in the afternoon, we got off at the cotton field and worked until dark.”

Agricultural scientist at Minnesota

More than a half-century lies between those fields in southwestern Georgia and the desk at Swanlund Administration Building on the Illinois campus, where Jones will begin his tenure as Chancellor, effective Sept. 26. But consistent across that time span is an intellectual curiosity that has propelled him and his career in higher education.

Early on, he was curious about plants. “Curious about how a green cotton plant produces its white, fluffy material, and how did that happen,” Jones says. “You know, just a curious child. I knew from the time I was about 8 or 9 years old that I had a very strong interest in science.”

Thanks to mentors in high school and at Fort Valley (Ga.) State University, where he received a bachelor’s degree in agronomy, Jones went on to the University of Georgia as one of the first African American students to enroll in crop physiology graduate studies. Later, as a doctoral student at the University of Missouri, he held a prestigious George Washington Carver Fellowship. Even before his thesis was written, he had accepted a faculty post at the University of Minnesota, where he launched a multidisciplinary research program in corn physiology and molecular biology. It was there, where he would remain for 34 years, that Jones came to appreciate the importance of the land-grant mission. It is that mission, he says, that makes his forthcoming position “a dream job.”

“The University of Illinois is one of the most highly ranked and outstanding land-grant institutions in the country,” Jones says. “You think about your mission in the context of aligning academic resources to solve some of the complex problems facing society. And that’s at the root of the historic land-grant mission. It is a dream that’s come true for me—to have the opportunity to lead this University as part of my 37-plus years in higher education administration. This clearly will be the capstone experience to all of that.”

Academically, Jones has won attention for his research on factors that affect the growth of corn kernels, which he cultured in his lab on the Minnesota campus, achieving a reputation as a leading expert in the field. Among his collaborators was Fred Below, a crop scientist at Illinois. “He was a mentor to me. I was in awe of his work,” Below says. “He was also quite the gentleman, quite helpful.”

In the 1990s, Jones visited Below’s lab on the third floor of the Edward R. Madigan Laboratory on the Illinois campus. The two worked together for a week, collaborating on methods for studying corn kernels under stress from nitrogen (Below’s interest) and heat (Jones’ area). “Jones was working on heat stress with the idea that there was going to be global warming,” Below explains. “This was 20 years ago. His underlying goal was to grow more food for the world.”

As part of a larger effort among crop physiologists and other agricultural scientists to boost corn production, Jones was successful. Over the past three decades, yields have increased 36 percent at an annual rate of roughly two bushels per acre.

University at Albany president

Meanwhile, other concerns came calling, sometimes literally. In 1986, Jones was again, as he puts it, “sitting around in the lab minding my own business” when interrupted by that ringing telephone. The next University of Minnesota President, Kenneth H. Keller, wanted Jones to direct a faculty program to mentor high-ability students of color, a responsibility that would claim 25 percent of his time. That request was the springboard for Jones’ administrative career.

Before joining Illinois, Robert J. Jones served as president of the University of Albany, State University of New York.

He would move through a series of posts of increasing responsibility at Minnesota, becoming senior vice president for academic administration in 2004. Six years later, Jones closed his lab. (“It was a sad day for me when he did that,” Below says.) In 2013, Jones left the Midwest to become president of the University at Albany, State University of New York.

In less than three years—concluding this autumn with his move to Illinois—Jones reshaped UAlbany. He initiated the largest academic expansion of the campus in 50 years, highlighted by new programs and partnerships across many areas. He was instrumental in creating the nation’s first College of Emergency Preparedness, Homeland Security and Cybersecurity at the university. He facilitated an agreement with Albany Law School, bringing the oldest private law school in America into the SUNY fold. And he helped launch the university’s new College of Engineering and Applied Sciences—work that is especially germane to the ongoing evolution of the Carle Illinois College of Medicine.

“Making the new College of Medicine a fantastic success is really important,” notes U of I System President Killeen, whose time as SUNY’s vice chancellor for research briefly coincided with Jones’ years there. (Killeen, who became the System president in 2015, also had his office on the UAlbany campus.) “I was delighted to see Jones’ name appear in the search,” he says, referring to the rigorous eight-month process during which a campus advisory committee vetted more than 100 candidates, narrowing the number down to about 30—a list then culled by Killeen to four finalists.

Of Jones’ future administration, Killeen predicts, “There will be a whole host of issues we’ll be working with together.” Beyond the challenges posed by the state budget gridlock and the work required to maintain institutional excellence, Killeen envisions U of I leadership promoting “a greater level of interaction” with the citizens of Illinois, “building up and out the talent base for people’s prosperity so those tax bases can afford adequate funding for higher education in our common interest.” As outlined in the recently approved University of Illinois Strategic Framework, this is the land-grant mission of the 21st century. And it’s one that Jones “cares a lot about,” says Killeen, who is confident the new Chancellor will be good at forging relationships among the University, the city of Chicago and communities statewide.

“He’s very personable,” Killeen says. “He’s got a good sense of humor. He’s a good listener and a good storyteller.”

Archbishop Desmond Tutu

Jones will have ample opportunity to demonstrate his listening skills during his first 150 days in office when, as he has promised the campus community, “You should expect to see me a lot—and hear me a little. I have a big learning curve ahead of me, and I know I won’t address it by talking.”

His first 150 days:

You should expect to see me a lot—and hear me a little. I have a big learning curve ahead of me, and I know

I won’t address it by talking.”

That he’s a good storyteller is charmingly apparent. The story that began with a phone call in 1984 has taken him to South Africa and Namibia to meet with thousands of young black men and women who are eager for the chance to escape political oppression and earn a degree at a U.S. university. It also has brought him close to program founder Tutu.

Tutu’s vision for South Africa post-apartheid, Jones says, included the idea that “the best path forward for the country was to educate black South Africans in a place where—notwithstanding their race, their color—they could get a good education without the oppressive issues that occur when black students try to enroll in predominantly white institutions.

“When I go back there now,” Jones continues, “invariably, if I ask enough questions, I run into people educated in this program who are rectors and vice rectors of institutions. They are running nonprofit organizations. They’re small business owners. They’re managing directors of some of the biggest companies in South Africa. It is truly one of the most profound things I’ve experienced in my almost 40 years of work in higher education.”

The program ended with the apartheid regime in 1994. But the friendship with Tutu has endured. When Jones was inaugurated president of UAlbany on Sept. 28, 2013, Tutu joined the ceremony via a live video feed. The retired archbishop of Johannesburg promptly “told a joke about me,” Jones recalls. “Tutu said, ‘Bob’—he’s the only person I usually let get away with calling me Bob—‘Bob never wanted to be an administrator. But I guess God had other plans.’ Then he broke out into this big smile.”

And, on a hot summer morning not long before starting his dream job, so does Chancellor-to-be Robert J. Jones.