Big Beats

Photo by L. Brian Stauffer/UI Public Affairs

Photo by L. Brian Stauffer/UI Public Affairs On Oct. 31, 1925, a cold damp day, an underachieving Fighting Illini football team was in Philadelphia, facing the powerful Quakers of the University of Pennsylvania. Illinois’ record was a desultory 1 and 2, but the Illini felt it had something to prove: Mighty Penn had been rather full of itself about its squad and about the superiority of eastern football. However, the Illini weren’t exactly pushovers. Illinois had Red Grange, the best player in college football. They also had a band.

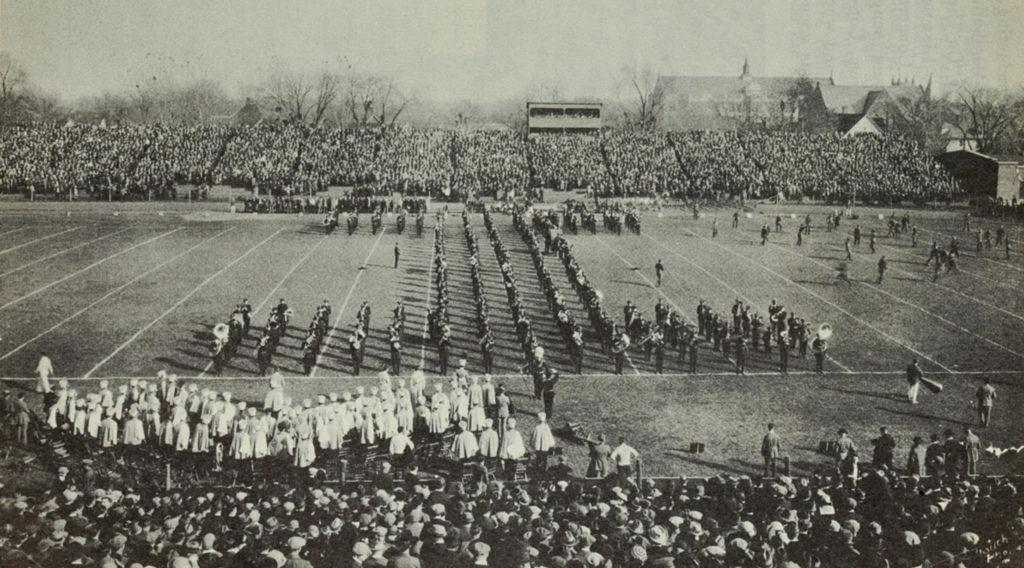

“A murmur went through the stands as the procession came on through the gate—50 pieces, 75, 100, 150,” read an account in the Illinois Alumni News. “As the huge musical organization kept on coming, the crowd on all sides roared its amazement—and as the entire marching organization came into full view everybody in the stands was on his feet, yelling his delight.” Years later, Grange recalled that moment in his memoirs. “What an inspiration we got when the magnificent 150-piece U of I Marching band performed in front of the stands just before the kickoff,” wrote Grange. “They electrified the crowd with their snappy formations and stirring music. There had never been anything to equal it on an eastern gridiron.” The inspired Illini demolished Penn 24-2, and went on to sweep the remainder of its schedule.

That may have been an early moment of national recognition for the Illinois marching band—which was not yet called the Marching Illini—but it was hardly the first. The band was already a deep source of pride and inspiration in its home state, and admired throughout the Big Ten.

Spring tour 1929, in front of Armory: Band member grips are piled on top of buses. (Photo courtesy of UI Archives, “We’re loyal to you, Illinois”)

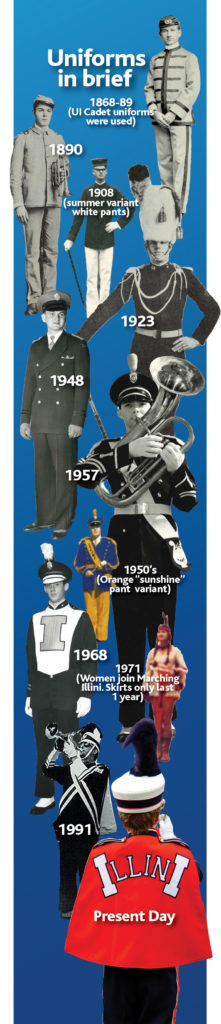

Formed by students shortly after Illinois was founded in 1867, the band, like many college bands of the era, had its origin as a musical unit that accompanied the campus military squad during drills and other ceremonies. The band proved popular, and began playing at Illini baseball games. When the University created a football team in 1890, the band began marching to entertain the crowd. It’s been a mainstay on autumn afternoons ever since.

John Philip Sousa (left) and Albert Austin Harding at the National Music Camp in Interlochen, Mich., 1930s. (Photo courtesy of UI Archives, “We’re loyal to you, Illinois”)

The man who put the band on the map was Albert Austin Harding, 1916 FAA, who played and helped coach the band for two years before being named director in 1907. Then 27, Harding had played in marching bands in high school and with the Illinois National Guard, and he sensed that the showmanship and sheer razzmatazz of such a band would translate well to a college environment.

During his 43-year career, Harding enriched the University in many ways. He established other school bands, and used his close friendship with John Philip Sousa—who maintained that Illinois had “the world’s best college band”—to persuade the March King’s family to bequeath his papers to the school.

Harding established a standard of excellence and originality that continues to this day. Among the band’s firsts: performing the first halftime show at a football game (1907); and performing at the first football game broadcast on radio (1924). The Marching Illini was the first college marching band to release a compact disc (1986) and to

have a website (1994). The band had the Big Ten’s first female drum major (Debbie Soumar, ’80 FFA, MS ’96 FFA, in 1977) and was the first college band to march in the St. Patrick’s Day Parade in Dublin, Ireland (1992). In 2015, it performed in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade before an audience of 65 million.

These are proud accomplishments, but as anyone who has ever heard the rat-a-tat of drums and the blast of brass on an autumn afternoon, these firsts hardly convey the band’s visceral impact. “Hearing the band is the first sound of the football season. The Marching Illini are a crucial part of every game on Saturday,” says Joe Spencer, ’16 BUS, former Illini offensive lineman. “There is not a better feeling than running over to the north end zone and singing the Alma Mater with the Marching Illini and students after a big win.”

George E. Post, Class of 1909, was so inspired that he wrote a poem called Give Me The Band! for the December 1927 Illinois Alumni News (see below). It was printed below a photo of the marching band forming the word “Illini” on the football field.

Literally for decades, the band has created a special feeling that bonds the University community. What is often overlooked is that the inspiration runs both ways. As then-trumpet player Rachel Mueller, BUS ’12, told the Illio in 2010, she couldn’t wait for halftime, and watching students dance to the William Tell Overture.

“I love watching the students. I shouldn’t,” Mueller said. “I should be watching the drum major, but I just can’t help it.”

Give Me The Band! was written by George E. Post for the December 1927 Illinois Alumni News.

I sat afar in some high-numbered seat,

A lone alumnus at the year’s big game,

A stranger dumbly wondering why I came,

With heavy heart that prophesied defeat

Until there beat across the autumn air

The curt staccato of the vibrant drum.

With misty eyes I leaped to see them come.

The band! A splendid, gloriously fair!

Trombones agleam and cymbals flashing high,

Straight lines of color sweeping down the field;

And then the sudden burst of music pealed

Re-echoing from stadium and sky;

Awakening the past; baptizing me

Anew with floods of that delicious joy

Resurgent through the songs of Illinois;

And setting my pent college spirits free.

No charging back, no speedy end can claim

My fealty for long. Give me the band!

It, it alone, retains power to command,

Is sole surviving glory of the game.

It plays! And youth comes charging rampant back

Into my heart, asserts its ancient sway,

Revives my college spirit for a day.

Give me the band! On, to the great attack!”

The Marching Illini have been a mainstay at football games since 1887. (Photo courtesy of UI Archives, “We’re loyal to you, Illinois”)

The Original Architect

Young Albert Austin Harding circa 1910. (Photo courtesy of UI Archives, “We’re loyal to you, Illinois”)

There are people who pursue a particular career their entire lives, and then there are people like Albert Austin Harding, one of the greatest college band directors of all time. He wanted to be a sanitary engineer until the day he got a job with the UI band program.

You might call it the day he finally began to march to the sound of his own cornet. Certainly, leading a band seems to have been his destiny. This was, after all, a person who became band director at his high school in Paris, Ill., before he even graduated from high school.

“I tried to get out of it, but there was no use. That music simply followed me around,” he told the Illinois Alumni News.

As an engineering major at Illinois, Harding played fullback on the football team. He joined the University’s military band at the urging of legendary coach George Huff (an “excellent” bass drummer himself, according to University of Illinois Bands). Harding played cornet and rose to first chair. In 1905, he was hired to help direct the band program. Two years later, he was in charge, and held onto that baton until 1948.

During his career, Harding not only developed the marching band’s performances at military ceremonies and sporting events, but he enlarged the program to include concert band music and transcriptions of symphonic and chamber pieces. Under his direction, the school’s entire music program acquired national recognition. Today, he is recognized not just as the father of the only Marching Illini, but as one of the seminal architects of university band programs as we know them today.

Today’s Marching Illini

Some 378 students, representing virtually every college and major, participate in the Marching Illini.

The number is fixed, and competition for spots is robust. Each year, the band turns away some 400 students who audition for spots in the Marching Illini. Once a student joins, however, the Marching Illini is like a family.

Encouraged by her father, an Illinois alumnus who attended every Illinois football game as a student in the 1980s, Gabby Hinner, ’17 ENG, ’17 LAS, earned a spot on the Marching Illini as a tenor saxophonist and worked her way up to section leader. She holds fellow band members as some of her closest friends.

“Participating in the Marching Illini gave me a constructive way to focus on something besides school work,” she says. “It shrinks the University down a bit. I went to a high school of about 325 students, which isn’t too much smaller than the band. I found the transition [to] a Big Ten university much easier this way.”

The Marching Illini performs at all home football games and other campus events. It also performs at the annual Illinois Marching Band Championships and the Marching Illini Live in Concert. The Marching Illini performs at Bands of America events and conducts exhibition performances throughout the Midwest, including the season opener of the Chicago Bears.

Marching Illini perform during halftime at homecoming game. (Photo by L. Brian Stauffer/UI Public Affairs)

Marching Illini By The Numbers

More than 750 students audition each year

378 students make the cut and it breaks down like this:

- 174 brass

- 84 woodwind

- 36 Drumline

- 28 Guard

- 28 Illinettes

- 3 drum majors

- 2 twirlers

- 6 graduate staff

- 8 undergraduate staff

- 9 support staff

60,670 spectators when stadium is filled to capacity

120 practice hours per semester for roughly 30 performances per year

Performed at 17 Bowl Games

- Rose Bowl 1952, 1964, 1984, 2008

- Liberty Bowl 1982

- Peach Bowl 1985

- All-American Bowl 1988

- Citrus Bowl 1990

- Hall of Fame Bowl 1991

- John Hancock Bowl 1991

- Holiday Bowl 1992

- Liberty Bowl 1994

- MicronPC.com Bowl 1999

- Sugar Bowl 2002

- Texas Bowl 2010

- Kraft Fight Hunger Bowl 2011

- Zaxby’s Heart of Dallas Bowl 2014

Notable Firsts

Throughout their history, the marching bands at Illinois have been innovators in many areas.

Illinois was the first to form school letters in formation; first to sing a capella on the field (1920); first to bear a giant school flag; first to use bugles in a field show (1913-14); and first to use sousaphones, in 1906-07 (28 sousaphones are part of the Marching Illini today).

Other key moments in the band’s history include:

The first marching band at Illinois was a military band formed when the University was called Illinois Industrial University. Its first documented march was an official procession that took place Sept. 13, 1872, to open the University’s new drill hall and mechanical shops.

The band performed its first football halftime show in 1907 during the season opener (a loss) against the University of Chicago. It played while marching in a Block I formation.

In 1971, women were admitted into the Marching Illini (they had been temporarily admitted during World War II).

Gary Smith, who directed the Marching Illini from 1976-98, is responsible for much of the band’s modern look, from the design of its current pregame show to the addition of the Illinettes dance squad.

Why Sousa Loved Illinois

With the rich history of marching bands at Illinois, it’s fitting that the University holds the library of The March King himself—John Philip Sousa.

The University’s possession of Sousa’s library can be attributed to the peerless quality of the band program in the early 1900s and the March Master’s close friendship with Albert Austin Harding.

Harding first met Sousa, a native of Washington, D.C., in 1906 at the home of University President Edmund James, where Sousa was honored during his band’s visit to Urbana-Champaign. Later that night, Sousa directed his band as it played Celebration March Song and Illinois Loyalty.

The friendship between Sousa and Harding grew, with Sousa later being named honorary conductor of the University’s Concert Band. In 1929, Sousa wrote University of Illinois March, regarded as one of his finest march compositions.

Upon Sousa’s death in 1932, his family agreed that the band director’s library should be housed at the University of Illinois. Some 3,000 compositions and other documents in the late director’s

library were shipped to Illinois. The contents came in 42 trunks and weighed nine tons.

Today, the collection is housed in the Sousa Archives and Center for American Music, which is part of the University of Illinois Library and University Archives. In 2004, upon the 150th anniversary of Sousa’s birth, Illinois curator Scott Schwartz—now director of SACAM—made the contents from Sousa’s library available to the public. “If music is just notes on a page in a box, it’s silence,” Schwartz says.

(Uniform images 1868-89 Illio 1895-96; 1890, 1908, 1923 and 1991 courtesy of UI Archives; 1948, 1957, 1950’s, 1968 and 1971 courtesy of Joe Rank and Present Day courtesy of UI Public Affairs)

Band Standards

The Marching Illini is always evolving, though slowly. That includes, most importantly, its music. In the words of former director Mark Hindsley, who led the Marching Illini and other University bands from 1934-70, “few songs have instant success.”

Once they arrive, however, they don’t easily depart. That includes the Hail to the Orange, now part of the time-honored Three-in-One formation. Written in 1910, the song’s composers, students Howard Green and Harold Hill, found that they literally could not give the song away. Told that it lacked punch, the tune was rewritten for Sigma Alpha Epsilon under the title Hail to the Purple before it was copyrighted as an Illini song.

Other songs have staying power, such as Oskee Wow-Wow (also written by Green and Hill) and Illinois Loyalty (written in 1907 by rhetoric instructor Thatcher Guild).

The most enduring song is The Star Spangled Banner, played in the star formation. The band then turns to the visitor seating section to play the visitors’ fight song. During the last 32 counts of the song, members fall into the Illini formation to play Illinois Loyalty, Oskee Wow-Wow and William Tell before forming a tunnel for the football team.

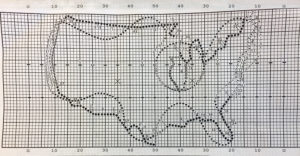

Formation Building

As you might expect, it’s no small feat to turn an idea into a new performance by the hundreds of musicians who make up the Marching Illini.

The process starts in spring, says Barry Houser, MMUS ’09, director of the Marching Illini, when students and staff brainstorm show concepts based on themes, anniversaries and other significant events.

Once the concepts are confirmed, Houser searches for song titles with great musical arrangements or works with the band’s music arrangers to put together songs—an expensive and time-consuming process, Houser says, as copyright permission costs have skyrocketed over the years.

Next is a “dissection” of the song—in other words, a count breakdown that tells the director how many pages of drill or number of formations they need to create.

Band directors depend on the count sheets for initial formation sketches on paper, but to finalize the performance blueprint they rely heavily on Pyware, a computer program for bands. After an app was developed a few years ago, students were able to use their smartphones to see their exact coordinate for each formation, diminishing the learning curve significantly.

Once the show is created in Pyware, good old-fashioned hard work comes next. The Marching Illini practice 18-20 hours a week in rain, snow or sunshine, with some formations perfected the week before they’re performed, Houser says.

Along with the formation, band members are expected to master a wide repertoire: At any given football game, they play nine songs during the pregame performance, such as Illinois Loyalty and Oskee Wow-Wow (they also play the opponent’s fight song); a halftime program of two or three songs, which are new for each game; and a selection of dozens of songs that the band plays from the stands during the game, with a tune attached to each down. In all, the band will play up to 60 songs during the course of the season. “The students must be focused, resilient and ready to work,” Houser says. “They make the magic happen each day, week, month and season.”