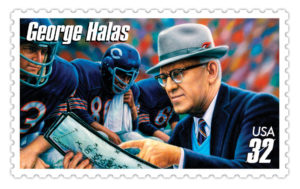

Papa Bear

In 1920, Halas founds the Decatur Staleys, which changes its name to the Bears in 1922. He also plays a pivotal role in the establishment of the

National Football League. (Photo courtesy of the Chicago Bears Football Club)

In 1920, Halas founds the Decatur Staleys, which changes its name to the Bears in 1922. He also plays a pivotal role in the establishment of the

National Football League. (Photo courtesy of the Chicago Bears Football Club) One hundred years ago this month, a rough-hewn Chicagoan reported for football practice at Illinois Field. George Stanley Halas, ’18 ENG, was entering his senior year at Illinois, his first season with the Fighting Illini varsity. Young Halas also was entering a remarkable five-year period in which he would star for the Illini, beat the Illini, precede Babe Ruth as the New York Yankees’ right fielder and found the biggest sports league in world history.

He was lucky to be alive. Two years before, the skinny son of immigrants from what is now the Czech Republic took a summer job with Western Electric. Each year, the company staged a holiday picnic at the Indiana Dunes, a 40-mile boat ride across Lake Michigan. Young Halas had his ticket to the 1915 picnic, but he was running late. He reached the dock just in time to see the steamer SS Eastland, crowded with Western Electric workers, sinking. Eight hundred and forty-four people died in the worst shipwreck in Great Lakes history. Workmen carried their bodies to a makeshift morgue, an icehouse on the future site of The Oprah Winfrey Show studio.

Halas called the wreck “appalling.” News reports listed him among the dead. He shocked friends who stopped by the Halas house to offer condolences, jumping out like a ghost in the flesh.

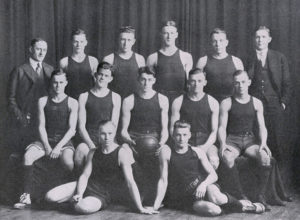

The George Halas-led Great Lakes Navy Bluejackets beat Navy, 7-6. (Courtesy of UI Archives/Illio 1920)

That fall, the 6’, 170-pound Illinois sophomore tried out for halfback. Once again, he was lucky to survive. Burly upperclassmen thrashed him until Head Coach Bob Zuppke said, “Get the kid out of there before he gets killed.” Halas swore he’d bulk up: “Wait till next year.” The following spring, a little heavier, he batted .350 for an Illinois baseball team that won the Big Ten title. A broken leg ruined his next football season, but he recovered in time to lead the basketball team against Wisconsin in a showdown for the 1916-17 conference crown. With the clock running out, Halas made a long set shot to win the game.

Flash forward to 1917: Finally healthy enough to play for Zuppke, the legendary coach who invented the huddle and the onside kick, Halas led the Orange and Blue to a 5-2-1 record. At the postseason football banquet, Zuppke said goodbye to the seniors: “Just when I teach you fellows how to play football, you graduate and I lose you.” With no pro league to play in, the seniors would have to leave the game behind.

“Football,” said Zuppke, “is the sport that ends a man’s career just when it should be beginning.”

As Halas recalled decades later, “His words would govern the rest of my life.”

With World War I raging in Europe, Halas earned his degree in civil engineering and joined the U.S. Navy. Assigned to the Great Lakes Naval Station near Waukegan, Ill., he organized a football team stocked with college stars. In 1918, his Great Lakes Navy Bluejackets took on the best college teams and went 6-0-2. The Bluejackets thumped an undefeated Rutgers squad led by All-America end Paul Robeson, the future Broadway and film star, by a score of 54-4. They faced off against Zuppke’s Big Ten champs and beat the Illini, 7-0. They battled Knute Rockne’s Notre Dame Fighting Irish to a 7-7 tie, then closed their schedule against unbeaten Navy, a juggernaut that had won its previous game 127-0. To make matters worse, Ensign Halas and his recruits had to play the mighty Middies on their home field in Annapolis. Still the Bluejackets won, 7-6. Six weeks later, they won the 1919 Rose Bowl thanks largely to Halas, who scored a touchdown, picked off a pass and was named Player of the Game. “The only game I ever starred in,” he called it.

But there were more highlights to come.

At Illinois, Halas earns a degree in civil engineering and plays three sports—football, basketball and baseball. He bats .350 for Illinois team that wins the Big Ten title in 1915 and hits the gaming-winning shot against Wisconsin for the conference crown in 1916. (Photo courtesy of UI Archives/Illio 1919)

Two months after the Rose Bowl, three-sport-star Halas tried out for baseball’s New York Yankees. He impressed them enough to win a $400 contract. Speed was his greatest asset, but it backfired the day he slid into third base so hard that he jammed his hip—an injury that nagged him the rest of his life. He played in a dozen big-league games, half of them in right field, batting .091, with two singles—his only major league hits—before manager Miller Huggins sent him to the minors. A year later, the Yankees bought Babe Ruth from the Red Sox to play Halas’ old position.

Halas went to work for the Staley Starch Company in Decatur, Ill. He had a desk job, but his primary duty was to organize a semipro football team to promote the company. Soon the company team featured several of his old Illinois teammates and other college stars enticed by the offer of $25 a week for factory work and $100 a game. The Decatur Staleys made short work of the beer-league clubs they played.

On Sept. 17, 1920, Halas represented the Staleys at a meeting in auto dealer Ralph Hay’s showroom in Canton, Ohio. Hay ran the Canton Bulldogs, one of four semipro teams in Ohio. Along with those four and Halas’ team, five other clubs were represented: the Chicago Cardinals and Rock Island Independents from Illinois; Hammond Pros and Muncie Flyers from Indiana; and Rochester Jeffersons from New York. As the meeting wore on, the men wet their whistles with illicit beer—Prohibition had started that year—and drew up a schedule for the first season of the American Professional Football Association. Halas, recalling Zuppke’s words at the 1917 football banquet, thought it was time to kick off a new sport: fully professional football.

At Halas’ urging, the group soon gave the APFA a new name: the National Football League. During the league’s early years, Jim Thorpe doubled as commissioner and player-coach of the Canton Bulldogs. One day, Halas stripped the ball from Thorpe and ran it 98 yards for a touchdown, setting a record that stood for half a century. The Staleys moved to Chicago, where player-owner Halas renamed them as a tribute to the Cubs, who let his poorly paid team play at Wrigley Field. Reasoning that footballers are bigger and meaner than baseball players, he called them the Bears. Their official colors were and still are the orange and blue of his beloved Illini.

At a time when college football was far more popular than the pro game, Halas would pace Clark Street outside the ballpark, hawking tickets to Bears games. He charged extra for tickets that allowed a few fans to sit on the visiting team’s bench. In 1925, he put the NFL on the map by signing college football’s greatest star, Illinois halfback Red Grange. Halas took Grange and the Bears on a barnstorming tour that drew record crowds from coast to coast, establishing pro football as a viable sport.

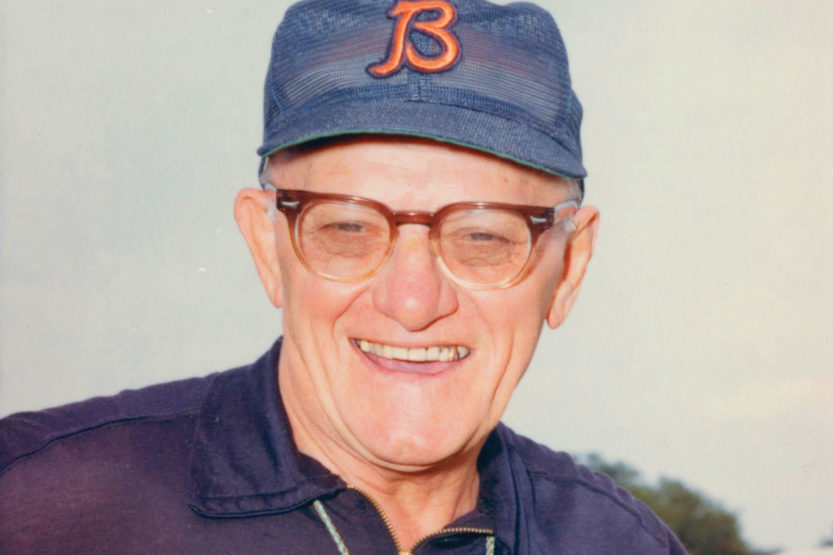

Through it all, the fierce, flinty, foul-mouthed fighter from Chicago’s West Side did as much as anyone to shape the modern NFL. He retired as a player in 1930, coached the Bears until 1967 and ran the club until his death in 1983 at the age of 88. He led the Bears and the league through the Great Depression to postwar prosperity and a late-century miracle he’d dreamed of as a young man: a time when pro football surpassed baseball as America’s true national pastime. In 1963, he became a charter member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, where his sculpture is practically within spitting distance of the spot where he and the other founders sipped illegal suds while launching the NFL. To visit the Hall of Fame, take Interstate 77 to Canton and turn left on George Halas Drive.

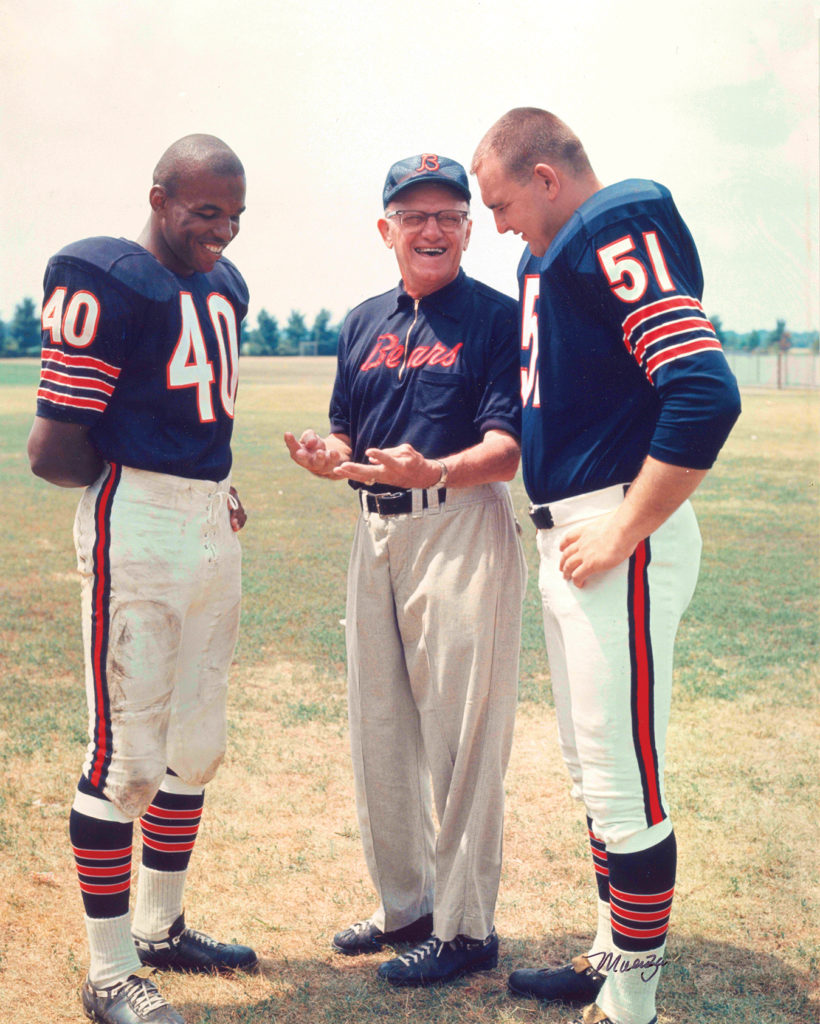

Halas talks with two future NFL Hall of Famers, Gale Sayers and Dick Butkus. Halas coached the Bears from 1920-29, 1933-42 and 1946-67, amassing a record of 318-148-31. (Photo of the Chicago Bears Football Club)

George Halas led the Bears to six NFL titles from 1921-65. He coached them to 318 victories, second on the all-time list to Don Shula, but his influence isn’t limited to the record book or the initials GSH woven into the Bears’ uniform. “When you talk about Bears history—Red Grange, Bronko Nagurski, Gale Sayers, Dick Butkus—you’re talking about Halas,” says Joe Horrigan, executive director of the Pro Football Hall of Fame. “When you see a Chicago Bear even today, you’re seeing George Halas. His legacy goes to the very roots of the National Football League—player, coach, owner, founder—and nobody else comes close.”

This month, exactly a century after Halas’ senior year at Illinois, the University will induct an inaugural class of athletes into a new Fighting Illini Hall of Fame. The first 28 honorees will include Halas, Zuppke, Grange and Dick Butkus, ’65 AHS, who recalls his old coach as the meanest man he ever loved.

Two years ago, the Bears unveiled a bronze statue of Halas. “I’m not sure what that statue is made of,” Butkus said, “but whatever it is, it’s not as strong or as tough as George Halas was.”

This year, Butkus says he’s proud to join his old boss in the Fighting Illini Hall of Fame. “I was born in Chicago,” he says. “Born to be a Bear, born to play for Papa Bear.”