Falls’ Reign

Goodman Theatre’s

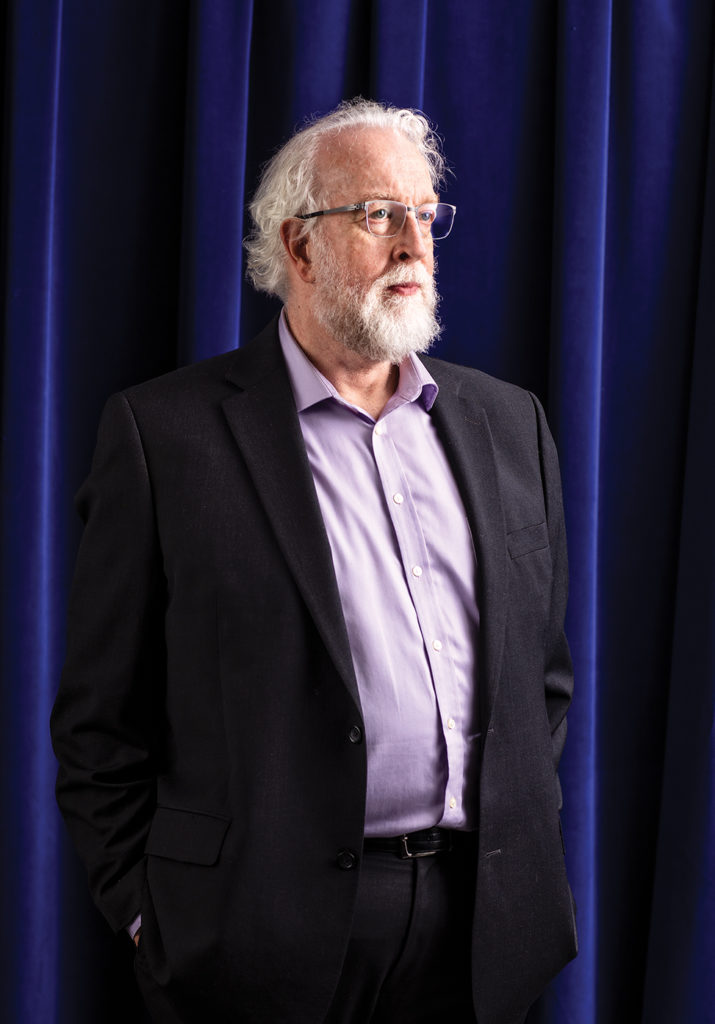

artistic director Robert Falls. (Image by Callie Lipkin)

Goodman Theatre’s

artistic director Robert Falls. (Image by Callie Lipkin) Very little in theater can surprise Robert Falls, BFA ’76. An actor coming back from the dead is an exception, and that’s what we are witnessing this afternoon during a tech rehearsal for an upcoming production of Pamplona, a play centered on writer Ernest Hemingway’s final years.

One year ago, on the play’s opening night, 20 minutes in, actor Stacy Keach lost his place and became confused. Hustled into the wings and later to a hospital for triple bypass surgery, Keach not only survived his heart attack, but is back to tackle Papa again this summer.

“After 40 years of doing this, I feel I’ve seen just about everything,” says Falls in the semi-dark of the Goodman’s Owen Theatre. “I’ve seen actors’ bad behavior and acts of generosity. I’ve seen plays that bombed and plays that became hits. Seeing an actor have a heart attack on stage was a first, and it’s something I hope I never see again.”

Actor Stacy Keach stars as Ernest Hemingway in Jim McGrath’s “Pamplona,” directed by Falls, who is the long-time artistic director at the Goodman Theatre. (Image courtesy of Goodman Theater)

The 2018 production of Pamplona was not only a phoenix triumph for Keach, it crowned four decades of Falls’ reign as artistic director of the Goodman Theatre. No one, it is fair to say, has put such an indelible stamp on Chicago theater. A genial man with a mass of white hair, Falls regards his unprecedented career as both remarkable and inevitable because he has always been compelled by theater. As an 11-year-old in the tiny Illinois farming town of Ashland, Falls read plays non-stop in the town library. In a precocious act of what he half-jokingly now calls “site-specific environmental theater,” he organized friends to run around a playground acting out an alien invasion à la The Day the Earth Stood Still while he described the plot for parents who followed him from sandbox to slide to swings. In one of those “Rosebud” moments, Falls sat on his living room couch watching Lee J. Cobb play Willie Loman in Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman on television while his father bawled, calling it “the most profound experience of my young life.

No surprise then that Falls played Willie Loman in his high school’s production of Salesman, directed Brian Dennehy in the smash 1998 Goodman production of the play, and then staged the premiere of Miller’s last play, Finishing the Picture, in 2004 at the Goodman.

Miller is a demigod to Falls, just below the hallowed triumvirate of playwright superstars—Shakespeare, Chekhov and O’Neill. Falls has directed memorable productions of all three. There was King Lear with Keach, several Chekhovs—an intimate The Seagull and a revelatory Uncle Vanya—and many O’Neills. Falls has a particular history with the Nobel Prize-winning dramatist, starting with Ah, Wilderness! at Illinois—he was the first undergraduate to direct in the main theatre of the Krannert Center—and continuing with storied productions of Long Day’s Journey into Night and The Iceman Cometh at the Goodman.

“I love the music of his language,” Falls says. O’Neill’s Irish Catholicism and his characters’ drinking habits also hit close to home. “I was raised an Irish Catholic, and there was a lot of alcoholism in my family,” he says. “[O’Neill] wrote his plays because he had to write them. You’ve got to be willing to go into the darkest places.”

At Illinois, Robert Falls directed the 1975 production of “Ah, Wilderness!” He was the first undergraduate to do so in the main theater of the Krannert Center. (Images courtesy of UI Theater)

A career launched at Illinois

Falls has consistently visited the dark places. It’s that daring that has made his tenure at the Goodman so memorable, along with his eagerness to tackle familiar dramas and enlarge their scope.

“One of his signatures has been the big project,” says Chris Jones, Chicago Tribune theater critic. “A lot of regional theaters get stuck in a groove of new plays by young writers, shrewdly written with six characters and three acts. Bob has managed to produce works of genuine heft and ambition and scale. He’s the poster child for a theater taking on a young, unproven director.”

Unproven but not without promise. Falls’ theater career was launched at Illinois. He delighted in his opportunities and made the most of them. “[We] were given a ton of freedom to act and direct; we did plays all over campus, in every nook and cranny,” Falls says.

Graduating with a BFA in directing and playwriting, he studied acting in New York City, then took over the fledgling Wisdom Bridge theater in Chicago, serving as its artistic director from 1977 to 1985. Three decades later, Jones is still talking about Falls’ eye-opening turn there. Reviewing a recent Hamlet, in which the prince scrawls graffiti, Jones recounted a similar epochal Falls’ moment. “One of the most famous off-Loop productions in the history of Chicago theatre,” Jones wrote, “[was] Robert Falls’ Wisdom Bridge Hamlet in 1985, wherein the actor Aidan Quinn, then 26 years old, famously spray-painted the words ‘To Be/Not To Be’ before spinning on his heels and telling the audience, ‘that is the question.’ ”

It was enough to make People magazine, Jones reminded his readers. “And it got [Falls] the job at the Goodman Theatre.”

That was in 1986. It didn’t take long for the national media to pick up on what was happening. In 1992, the Goodman received a Special Tony Award for Outstanding Regional Theatre, and in 2000, it moved from its cozy tenancy at the Art Institute of Chicago to its current marquee home on Dearborn in the Loop. Time magazine named the Goodman as one of the top five U.S. regional theater companies in 2003.

Falls’ unique run at the Goodman’s two-theater venue (the main stage Albert and the more intimate, flexible Owen) has resulted in every conceivable type of play—new work, re-imagined classics, musicals, star vehicles, one-person shows. Asked to name a few favorites, he demurs: “It’s like choosing among your children.” But once he starts, he can barely stop; it’s like auditing a crash course on 20th-century theater and playwrights. There was August Wilson, of course. The Goodman was the first theater in the country to do all 10 of Wilson’s plays. He loves Tom Stoppard; the Goodman did both his Arcadia and Rock ’n’ Roll. Falls is still delighted by the Goodman production of Alan Ayckbourn’s ingenious House and Garden, two simultaneous plays in which actors went from set to set (House in the Albert, Garden in the Owen).

Emotionally, Falls may be most connected to the “children” he has personally supervised—the plays he’s directed. He calls his two productions of Iceman “incredibly important.” The first featured Brian Dennehy in the starring role of Hickey; in the second, Dennehy switched to the role of Larry Slade while Nathan Lane took over as Hickey. Falls has a long, funny story—he has a lot of long funny stories—about the two actors as Hollywood roommates when Dennehy was playing cops on TV and Lane was trying to break into comedy. Lamenting that Lane was “pigeonholed in musicals,” Falls goes on to call Lane the “single greatest male performer, one of the greatest American actors.”

Falls has produced a wide range of works, including (Clockwise, top left): “The Iceman Cometh,” “War Paint,” “Father Comes Home From the Wars” and “Having Our Say: The Delany Sisters’ First 100 Years.” (Images courtesy of Goodman Theater)

“Like a great conductor”

It is one of Falls’ singular talents to coax name actors into risky, breakthrough performances at the Goodman, and occasionally beyond, on Broadway.

“Bob Falls is an extraordinary director. He is like a great conductor and a great coach,” Keach says. “Now that we have worked together for over a decade, we are almost able to read each other’s body language. I trust him completely. He’s a joy to work with.” Keach is particularly grateful for Falls’ support the night of his heart attack. “Bob saved me by coming onstage, giving me a hug, then ushering me off into the wings … . Later at the hospital, [before] my triple bypass surgery, even as I was about to receive the anesthetic, Bob assured me the time would come for me to return to the play.”

Loyal to the talented cadre of actors he has brought to the Goodman, delighted with most of the plays he has produced, Falls also can be candid: Miller’s final work, Finishing the Picture, for instance, won’t be making the highlights reel of Falls’ career. It didn’t help that, despite the obvious elements of autobiography, Miller refused to connect the dots. “He denied it was about his marriage to Marilyn Monroe and his mistress,” Falls says. “It was not a successful play.”

“I tend to be upbeat,” Falls says. “Over the years, there have been plays that weren’t so successful, but why point out a bomb? There’s always another play six weeks later. Picking plays is very much the center of everything I’ve done for 40 years.” (Image by Callie Lipkin)

Being “unsuccessful” is about the worst Falls will admit to. “I don’t like to dwell on the negative. What’s the point? I tend to be upbeat,” he says. “Over the years, there have been plays that weren’t so successful, but why point out a bomb? There’s always another play six weeks later. Picking plays is very much the center of everything I’ve done for 40 years.”

Here, life gets complicated for Falls, because unlike many theaters, which specialize in particular genres or styles, the Goodman is an equal opportunity presenter. New plays, classics, intimate dramas, big ensembles—they are all on the menu, and Falls has to serve up an enticing (and feasible) mix every season. The afternoon we spoke there was a production running of Having Our Say: The Delany Sisters’ First 100 Years—a winning drama about two Southern black sisters reminiscing about slavery and race and cooking grits. “I loved that play,” Fall says, but is quick to acknowledge that after a busy season of big casts and budget-challenging productions, it didn’t hurt to put on a two-character drama with a single set. The bottom line counts.

So does relevance. Falls acknowledges that much of the theater’s 2017-18 season was a response to the 2016 election—“not just Trump, but the circumstances in this country that led to his election.” Whether deliberately plotted or the result of subtler prescience, the Goodman’s past season touched all bases of the national debate. There was a play about the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo.; a searing drama about race (Father Comes Home from the Wars); a play about Muslims, Yasmina’s Necklace (“In 40 years, I’d never seen a Muslim family onstage”); a climate-change drama (Henrik Ibsen’s re-imagined An Enemy of the People); even a play about U.S.-Russia relations and the Reagan-Gorbachev talks, Blind Date.

Not in a New York state of mind

The Goodman also debuts new plays and likes to discover playwrights. Falls has plenty of help here: a busy staff of associates, workshop productions, contacts around the globe. Among those who have seen their work premiered at the Goodman is Rebecca Gilman, a favorite of Falls. He calls her 1996 play, Luna Gale, “the best new play I’ve seen.” Gilman, not surprisingly, is effusive in her praise of Falls.

“People say it’s the job of a director to ‘realize’ a new play,” Gilman says. “Bob does that, but so much more. He seems to live in my plays—to hear them and see them like I do, only better. I’ve said to myself, ‘Why didn’t I do that?’ But Bob is such a generous collaborator, he would probably tell me I did think of that, only I didn’t know it.”

At least three Goodman dramas have gone to New York, but Falls is clear: He never puts on a play with the thought it might land on Broadway. Occasionally, rarely, a production such as last year’s War Paint with Patti LuPone was designed to go from Chicago to New York. For the record, he is fond of both cities: Chicago is Falls’ home, a great theater town, but New York is tremendously exciting—Broadway is Broadway, stars, lots of glamour. “But also terrible, arrogant with lots of navel-gazing,” Falls says. “I’m a Pisces, so I see things both ways.

“I’m making wild generalizations,” he apologizes, lest anyone think that 40 years in theater can be reduced to a few pithy quotes for an interview.

He insists he doesn’t wake up in the middle of the night thinking, “Wow, what about Al Pacino playing Shylock [in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice]?” Matching stars to plays doesn’t interest him much. The process is more organic, which might explain the next big play he plans to direct—Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale. “It’s exciting and presents such a challenge,” he says. “Especially in light of the #MeToo movement. In the wake of brutality in [our] behavior toward women, forgiveness has always interested me and redemption—what is redemption? That’s what led me to it.”

Redemption could hardly have had a more telling moment than this past summer when Stacy Keach returned in Pamplona. Opening night, the actor finished his flawless 90-minute performance and came out to acknowledge the cheers and applause. For just a moment, he turned his grateful gaze to the white-haired man under the dark overhang off to one side, as if to say, “Thanks, I couldn’t have done it without you, Bob.”