Flash Point

On the anniversary of the Kent State shootings, students, faculty, and local residents march from Carle Park to West Side Park. (Image courtesy of UI Archives)

On the anniversary of the Kent State shootings, students, faculty, and local residents march from Carle Park to West Side Park. (Image courtesy of UI Archives) EDITOR’S NOTE

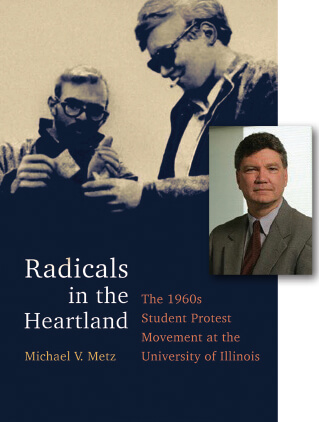

The 1960s were a period like no other in the history of higher education, as student unrest about the Vietnam War and other social issues overtook campuses nationwide, with thousands of students protesting, including those at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. To mark the 50th anniversary of the campus-wide student strike that occurred in May 1970 and to chronicle the events that led up to it, we present an excerpt from Radicals in the Heartland: The 1960s Student Protest Movement at the University of Illinois by Michael V. Metz, ’70 LAS.

The beginning of the end of the 1960s student protest movement was to come not with a whimper but with gunfire when Ohio National Guardsmen shot and killed four peaceful protesters at Kent State University; a cathartic, violent, nationwide cry of protest ensued, and soon after the movement effectively came to an end. But as the 1969–70 spring semester began at the University of Illinois, there was no hint that such a dramatic finish was at hand, as the new year felt much like the old, with no particular significance attached to the close of a decade. In Vietnam, the combat raged on; in Washington, D.C., President Richard Nixon still promised to “end the war with honor;” in Urbana, protesters still protested; and not very much seemed to have changed.

In early January, a new issue arose for the students to consider, as the University announced the Illiac IV project, a new, powerful supercomputer to be installed on the campus, paid for by the Dept. of Defense (DoD) and operated “approximately two-thirds of the time” for DoD purposes, one-third for University research. Of greatest concern to antiwar students, the new machine would “play a vital role in the development of more sophisticated nuclear weaponry.” The words “nuclear weaponry” figured prominently in large type headlining the front-page The Daily Illini (DI) story, adding to the article’s ominous tone. Such an announcement, at the time of virulent antiwar feelings on the campus, would not be accepted lightly.[1]

Chancellor Jack Peltason holds a “Teach-In” to discuss the new Illiac IV supercomputer, which was devoted in part to Dept. of Defense research. (Image courtesy of UIAA Photo Archives)

A student group, Radical Union (RU), was only a day behind Faculty for University Reform in issuing equally aggressive demands for the immediate cancellation of Illiac IV and, for good measure, an end to the University’s ROTC program as well.

The following day, two youths—Larry Allan Voss,’74 LAS, a sophomore University student in a wheelchair, and a high school student—were arrested after two firebombs were tossed through the window of the Champaign Police Department, causing first-degree burns to the arm and face of one officer. Voss was one of a group of 10 who had recently split off from the RU, forming a campus faction in support of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) Weathermen.

In the final week of February, a firebomb was thrown into the ROTC lounge in the University Armory, though it caused no damage to property or persons. That same night, Dr. Benjamin Spock, nationally known pediatrician and author of the nation’s perennially bestselling baby and child care book, now turned civil rights and antiwar advocate, spoke on campus. He reminded his audience that “the Declaration of Independence states that if people cannot get justice through legal means, they are entitled to cause a revolution.” “However,” he added, quickly raining on the parade of his cheering audience, “anybody who tries to start a revolution today would be reduced to a grease spot in two or three days.”[2]

March: patience spent, the storms begin

The spring outbreak of violence on the nation’s campuses that would mark the end of the protest movement began early at Illinois. The campus experienced three days of rioting, beginning on Monday, March 3, when representatives of General Electric, perhaps the largest Vietnam War defense contractor, arrived on campus for employee recruiting. There was no talk of a peaceful sit-in, though the tactic had successfully stopped the Dow Chemical interviews on the campus only a year before. The sit-in now seemed a relic of a quite distant past. Disorganized mayhem would be the students’ primary strategy with this military supplier, and by end-of-day Monday, the first of three days of riotous demonstrations, police would have 19 students and two nonstudents behind bars, charged with various counts of mob action, resisting arrest, disorderly conduct, fleeing police, illegal entry and criminal damage to state-owned property.[3]

Monday’s turmoil began after a noon gathering called by the Radical Union to rail against GE’s presence. The rally led to a loose march on the Electrical Engineering Building (EEB), where the recruiting interviews were to take place.

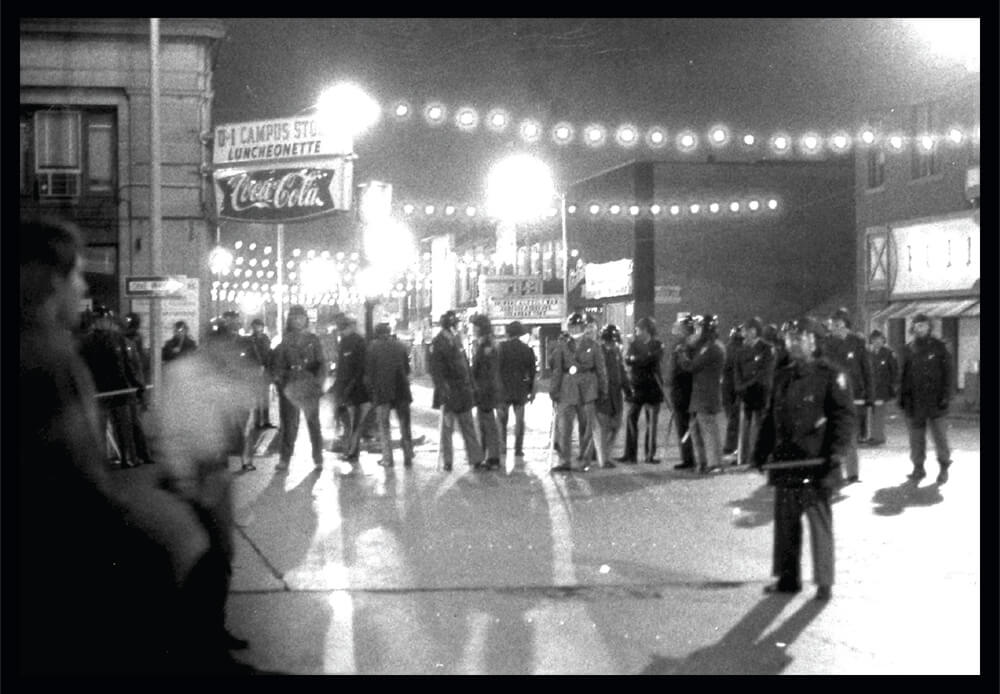

Monday evening, at 7:30 p.m., the RU held another rally, followed by another march on the now-dark-and-empty EEB, where a few more windows were broken; then the crowd moved into Green Street and marched through Campustown. Here, storefronts up and down the street suffered broken windows, with Follett’s Bookstore and McBride’s Drug Store particularly favorite targets, as popular sentiment held these were the worst of the price-gouging Campustown businesses. The crowd repeatedly clashed with Champaign police, who eventually forced the marchers back into the general area of the Quad, where more windows were broken, trashcans overturned and parking meters destroyed. The mob roamed the campus until nearly 10:30 p.m., when an emergency curfew, agreed upon by the University and both cities, was declared and announced with bullhorns, bringing quiet to the area.

Tuesday showed little improvement. An afternoon demonstration at a U.S. Navy recruiting station in the Illini Union led to an order to clear the building, and impatient Illinois state troopers, newly arrived on campus for the first time ever, moved in, shoving and clubbing resisting students. The Union was closed for two hours. That evening, a rally on the Quad led to a peaceful march of what the DI reported as an “enormous line of demonstrators…approximately 4,500” that moved from the Quad down the middle of Urbana city streets to the house of University President David Dodds Henry, ’76 HON, on Florida Avenue.[4]

After spending a relatively calm hour listening to speakers outside Henry’s home, 2,000 to 3,000 protesters broke away and began a march toward the Armory but were intercepted by local police and state troopers on the way. The crowd then separated into smaller groups and spread through the campus, breaking windows, with McBride’s again a target.

Retailers such as Follett’s and McBride’s were frequently vandalized when demonstrations spilled into Campustown. (Image courtesy of UI Archives)

Three hundred members of the Illinois National Guard appeared on the streets at 10 p.m. to enforce the continuing curfew. The guardsmen carried gas masks, tear gas and unloaded rifles. Bayonets were affixed to the rifles.[5] This was the first of several nights of tense face-offs between the students and the guardsmen during a nearly week-long occupation of the campus.

On Wednesday, a third night of campus rioting brought out the entire assigned contingent of 750 Illinois National Guardsmen, with gas masks donned but bayonets sheathed. In the evening, a two-hour march of nearly 2,000 protesters wound its way around the campus, with a lesser amount of rock throwing and window smashing than in previous nights. A student government representative attempted to calm the crowd but was shouted down by Michael Parenti, a visiting professor of political science from Yale University, where he had been a radical leader in the antiwar movement. Parenti called the student rep “a half-assed liberal pushing for representation in a powerless group,” then urged the crowd on—“To the Armory!”[6]

RU member Harriet Spiegel offered her perspective: “We’ve learned that the only thing that will end oppression is a material attack on the system…. This campus will never be the same.” By 10:30 p.m., the crowd had dwindled to 300 diehards, and the guardsmen marched into the crowd, breaking it into smaller groups. Police began rounding up those remaining, citing them for curfew-violation citations.

By week’s end, President Henry had expressed his “shock,” U of I Chancellor Jack Peltason, HON ’89, his “sadness,” and the trustees their “warnings of clear and present danger,” but remarkably, at the time, few articulated what seems obvious in hindsight. After years of peaceful protest against what many students considered an unjust, immoral and illegal war, with an unresponsive government and a University perceived as complicit with the war, the protesters’ well of patience was running dry. By this point, the great majority of students at Illinois and other campuses were opposed to the war and wanted it ended.

Quiet between the storms

The GE protests represented the most violent period in the 100-year history of the University to that point. But by the following week, GE was gone and the campus experienced a relative calm—only to be disrupted the week after when someone tossed a firebomb through a window at the Federal Building in downtown Champaign; fortunately, there were no injuries and only minor damage.

Another firebomb, failing to ignite, was discovered in Lincoln Hall; one that did ignite was thrown through a broken window of the Air Force Recruiting Station in Urbana, spreading fire and virtually destroying the office, causing more than $100,000 in damages to the building and adjoining structures.

Roger Simon, ’70 LAS, DI columnist, shared his thoughts on the growing anarchy:

“Nobody is in charge of the University anymore. Competing groups roam around grabbing parts of the action. The Board of Trustees grabs a chunk, the governor grabs a chunk, the mayors of Champaign and Urbana and the county sheriff take a chunk, and the kids in the street make a bid, too. President Henry and Chancellor Peltason are pretty well ignored by all the other groups….”[7]

May: The final month

The final stage of the Illinois student protest movement played out with the two imperatives of the decade interwoven: the treatment of black Americans by the dominant white society and the anguishing, seemingly never-ending calamity of the war in Southeast Asia.

The drama began on the last day of April. Edgar Hoults was a young black resident of north Urbana, a 1965 high-school graduate from a small town in Southern Illinois across the river from St. Louis. Following high school, Edgar wed his wife, Alice. The couple moved several times as Edgar searched for steady work, and when he found a job as a security guard at Follett’s Bookstore on the Illinois campus, he and Alice finally began to feel settled. In 1970, Edgar was 23 years old, Alice 21. They had two small children, and Alice was pregnant with a third.

During the last week of April, after a recent firebombing at the bookstore, Edgar was asked to work all-night shifts at Follett’s to help protect the store. As he worked through the night on the last day of April, Alice slept in the upstairs bedroom of their north-end duplex apartment. Early in the morning, she awoke suddenly to the sounds of “sirens, racing automobiles and men running.” She got up from bed, thinking that it was nearly time for her husband to return from work. As she looked out the front window of her home, hoping to see him arriving, Alice heard a gunshot at the rear of the house.

When she opened the back door, she saw her husband face down in a field of grass, bleeding. “I started shaking and crying,” she said. She attempted to go to her husband but was held back by neighbors. She saw Edgar lifted into an ambulance, and that was the last she would see him until shown his body at a local funeral home. No police officers came to her to talk about the shooting; no city official visited to explain the killing to her and her children.

The next day’s newspapers reported that Hoults had been shot in the back, killed by Champaign police after a high-speed chase that began on campus in the alley behind the bookstore, ran through north Champaign, and ended in the empty field in northeast Urbana behind his family home. The chase had begun early in the morning as Hoults drove away from the store, having finished his shift. Police would later report that they could not determine any reason Hoults might have fled from police except that he was driving with an expired driver’s license. The manager of Follett’s characterized the young man as a “good and loyal employee” and announced a pledge of $1,000 from the store to the family of the deceased.

The day the story ran, more than 100 University students staged an impromptu march from campus to the downtown Champaign police station; they demanded details of the killing but were rebuffed by city manager Warren Browning, who advised, “Don’t pass judgment ’til you know all the facts.”[8]

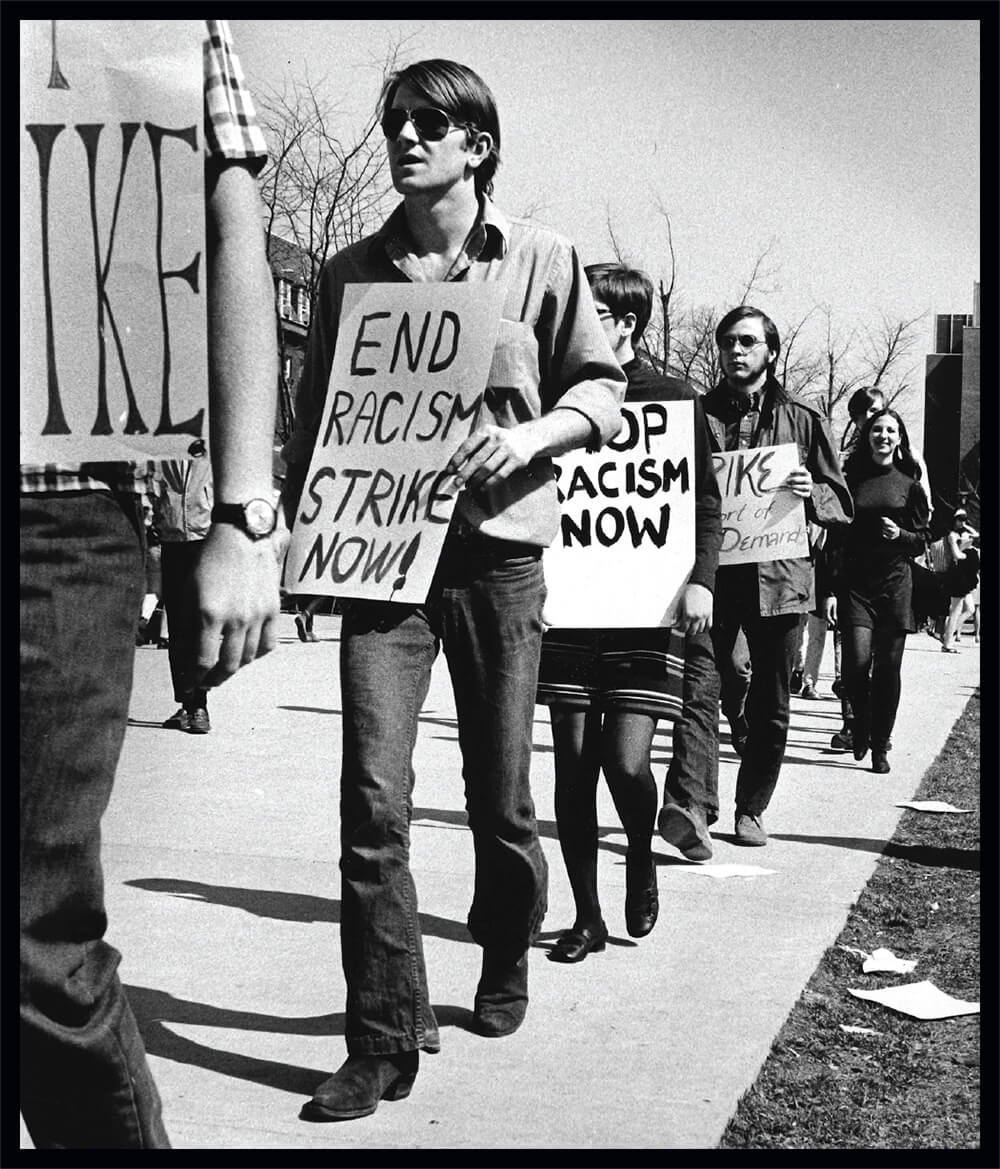

Social issues such as civil rights and racism also factored into the student protest movement. (Image courtesy of UI Archives)

In the second thread of this final act, that same day, the White House announced that American advisers would accompany South Vietnamese army troops on an offensive excursion into Cambodia, striking at North Vietnamese supply camps.

That night, the North End Ministers’ Alliance attended an emergency Champaign city council session, calling for the resignation of Chief of Police Harvey Shirley for Hoults’ killing, a ban on police use of the type of bullet that killed him, and the immediate hiring of 20 blacks into the city’s all-white police force. Sporadic gunfire was heard in the distance while the meeting ran, and the shooting would continue throughout the evening in northeast Champaign and on the north side of the campus. A spokesperson for the ministers summed up the blacks’ feelings: “The black community doesn’t trust the city council or the police department.”[9]

As the ministers spoke to the council, President Nixon addressed the American people in a nationally televised broadcast from the Oval Office. The “advisers” entering Cambodia, Nixon now explained, were actually several thousand U.S. combat troops supported by B-52 “Stratofortress” bombers, air cavalry helicopter gunships and covering artillery. With baffling logic, Nixon looked into the cameras and stated bluntly, “This is not an invasion of Cambodia…. We take this action not for the purpose of expanding the war into Cambodia but for the purpose of ending the war in Vietnam and winning the just peace we all desire.”[10]

Back in Champaign, as the city council meeting ended, the city manager released a statement identifying patrolman Fred Eastman as the officer who shot and killed Hoults; Eastman was now relieved of duty pending an investigation. In his statement, the DI reported Eastman claimed “he slipped and lost his balance as he pulled his revolver from his holster, causing the gun to discharge.”[11] Hoults had been brought down by a .38-caliber, hollow-point “dumdum” bullet, shot from behind as he left his car and ran from police. Such exploding bullets were not standard issue for the Champaign police force; patrolman Eastman had purchased the shells himself. That night, five people were shot and five businesses firebombed in the north end of Champaign and Urbana in a second night of violence.

Alice Hoults said adamantly that she “saw no purpose” to the violence that was sweeping the cities. “We don’t approve of bombings and shootings,” she said. “What I want is justice. Whoever committed this crime should be punished.” The manager of Follett’s came to her home with two weeks of her husband’s pay, $75 in donations raised by fellow employees, and a personal check from storeowner Dwight Follett, ’25 LAS, for $100, in addition to the $1,000 store pledge. As for her future, Alice told a reporter she could not stay in Urbana and would probably return to her family in the St. Louis area.

Campus disturbances began within hours of Nixon’s broadcast. Student and/or faculty declared strikes at Princeton, Yale, Smith, Stanford, and the Universities of Maryland and Oregon; on countless campuses, windows were shattered and firebombs tossed while police responded with tear gas and nightsticks. Thirty-seven college and university presidents, including those of Columbia, Princeton, Cornell, Notre Dame, Dartmouth and Stanford, but not Illinois, sent a letter to President Nixon calling for an end to the war. The Student Mobilization Committee pushed for mass demonstrations on the nation’s campuses, and the National Student Association suggested a nationwide student strike.

Three days after Hoults’ fatal shooting, on a Sunday, Champaign patrolman Fred Eastman was arrested and charged with voluntary manslaughter. The next day, May 4, Ohio National Guardsmen shot and killed four protesters on the campus of Kent State. The mostly young, nervous and poorly trained guardsmen would claim they had heard a sniper’s shot, but later review found no evidence to support that claim. President Nixon made a quick judgment: “When dissent turns to violence, it invites tragedy.”[12]

Strike: The final days

On the Illinois campus, students’ attention swiveled from Hoults’ death to Nixon’s invasion to the deaths at Kent State. On Monday, activists called for an evening rally at the Champaign city office to protest Hoults’ killing, then called another for Tuesday for a vote to join the nationwide strike. Demands discussed among the students ranged far and wide—freeing all political prisoners, ending repression of Black Panthers, impeaching Nixon, abolishing ROTC, ending University complicity with the war and, of course, immediate withdrawal of all troops from Southeast Asia.

Meanwhile, up and down the state, college students acted quickly in response to Nixon’s expansion of the war and to the Kent State deaths. Chancellor Peltason cancelled all classes and closed the University for three days, ostensibly to honor the deaths at Kent State, likely hoping the shutdown would provide a cooling-off period.

On the Urbana campus, reaction to the invasion began quickly and turned violent almost immediately. The Radical Union held their Tuesday night meeting in the Auditorium, where the audience overruled a speaker’s suggestion of a Thursday strike and voted to begin the strike the next day, Wednesday. They passed resolutions for cancellation of the Illiac IV project, for an impartial investigation into the Hoults killing, and for “liberation classes” to be held on the Quad for the duration of the strike—all nearly unanimously approved. As the meeting seemed to near an end, one student rose in frustration and criticized the group. “They’re doing things at every other campus in this country. We’re the only ones who are sitting around at a meeting.”[13] This charge initiated a lengthy debate on the use of violent tactics, following which the meeting attendees and hangers-on, several thousand in all, began an impromptu march around campus to various dormitories, notifying residents of the strike, shouting details, encouragement and invitations to join both the evening’s march and the next day’s strike. On their roundabout campus tour, the students paused long enough to break windows at Peltason’s office in the English Building and at the Administration Building, then wound their way past an ever-favorite target, the Armory, inflicting more damage, then finally weaving through Campustown, battering favorite targets such as Follett’s and McBride’s.

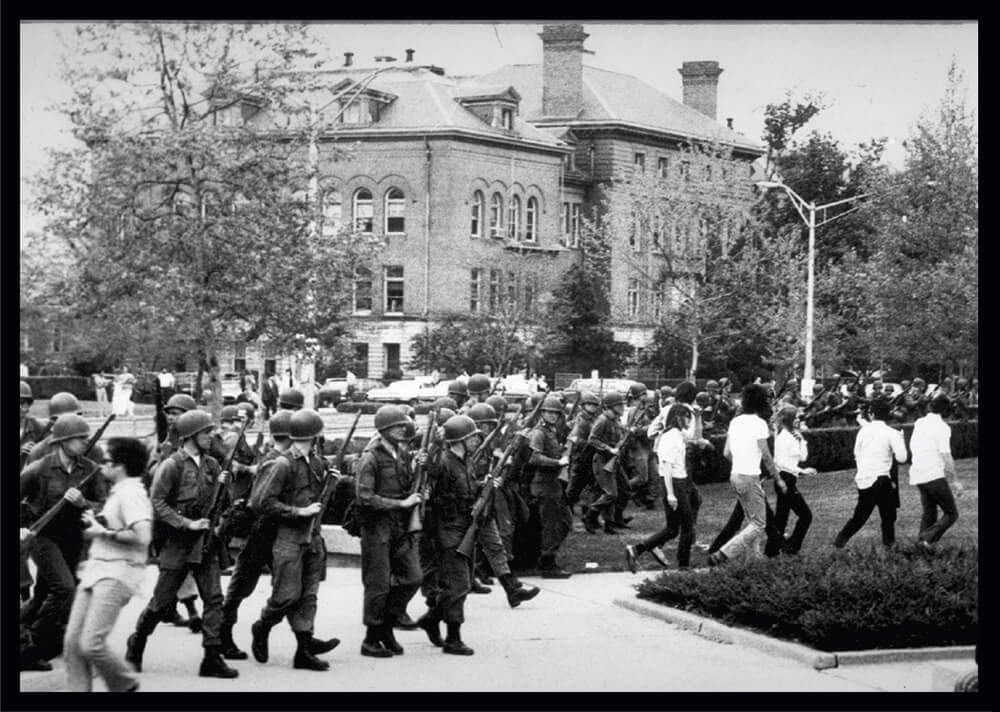

To quell protests on campuses statewide, Gov. Richard B. Ogilvie eventually called up the entire Illinois National Guard. (Image courtesy of UI Archives)

On Wednesday, the first day of the strike, Illiac IV protesters, newly reorganized into a group known simply as “The People” and not wanting their issue forgotten in all the excitement, announced an “Illiaction,” a Saturday rally with speakers Jon Froines and Rennie Davis, two defendants in the Chicago 8 trial. In addition, Black Panther Bill Hampton, brother of the late Panther Fred Hampton, would speak. By this time, the Illiac opponents had made a shift in their strategy. No longer protesting the presence of the machine on campus, “The People” were now focused on stopping the specific military purposes for which the DoD might use it, and they announced a march to follow the rally, one that would prove eventful, from the Quad to the new structure then under construction to house the supercomputer.

Within a few days of Nixon’s broadcast, more than 60 U.S. colleges and universities had either announced plans to strike or were already on strike. After the deaths at Kent State, the number of strike actions exploded, with more than 450 university, college and high school campuses across the country shut down by student strikes and an estimated 4 million students participating.[14] Campus ROTC offices, always an easy target, took a heavy toll—30 such facilities were bombed and/or went up in flames—while National Guard units were mobilized on 21 campuses in 16 states.[15]

On Wednesday morning, hundreds of students manned picket lines at dozens of campus buildings, not stopping students who chose to attend classes but attempting to persuade them otherwise. At noon, 4,000 people attended a rally on the Quad, listened to fiery speeches, then peacefully dispersed. However, in the afternoon, violence flared when a large crowd of 2,500 protesters blocked the driveway to the Illini Union loading dock, preventing trucks from making deliveries. Paul Doebel, ’50 BUS, the University’s chief security officer, did not hesitate to call in local police and state troopers, who made 50 arrests.

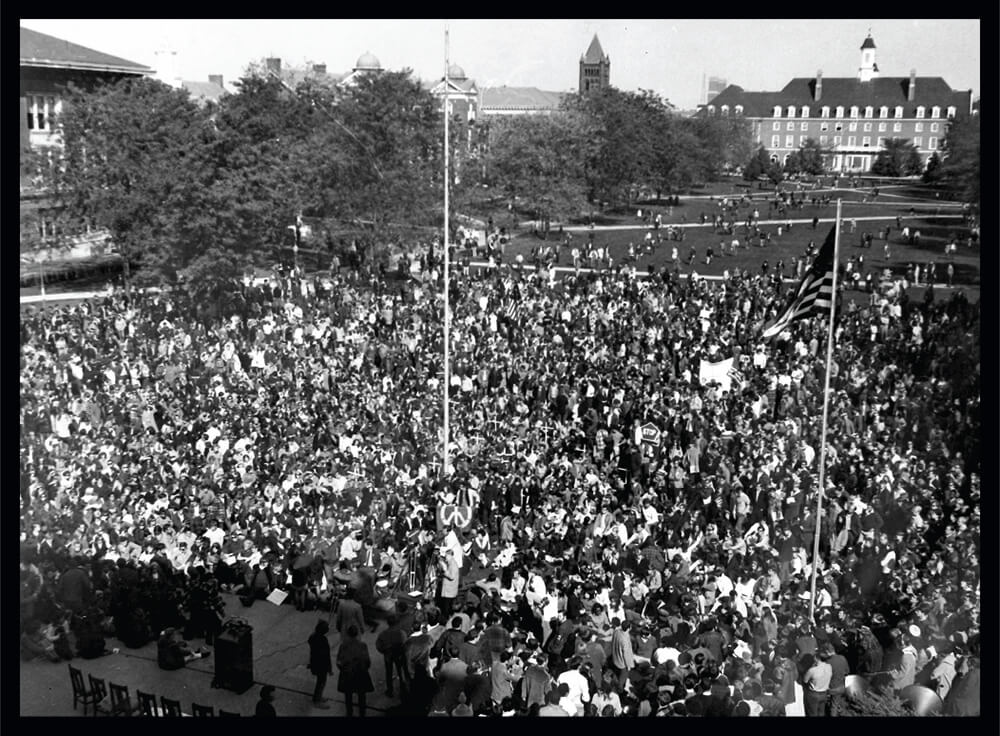

May 1970 brought forth the largest student protests on campus. (Image courtesy of UIAA Photo Archives)

That evening, nearly 4,000 people gathered on the Quad and self-divided into a nonviolent group and a “street action faction,” but the combined law-enforcement forces, out in strength, kept the crowd confined to the general Quad area as the curfew neared again, the crowd quietly dispersed.

At this point, an increasingly concerned Governor Ogilvie called up an additional 5,000 Illinois National Guardsmen and published a statement in the DI: “I call upon every student in our colleges and universities to cooperate with duly constituted authorities and stop the violence which threatens to destroy these schools.”

Published alongside Ogilvie’s warning, and lining up squarely behind the governor, Chancellor Peltason issued a statement condemning the strike and exhibiting little sympathy or patience for the protesting students. Throughout the strike, he would continue to stand on his belief that keeping the University open and operating as normally as possible was of the greatest import.

Despite Ogilvie’s and Peltason’s words, the Illinois strike, which ran from Wednesday, May 6, through Friday, May 8, succeeded at emptying most classrooms and freed thousands of students to express their frustration and anger toward the government and, by proxy, their University.

On the Quad, an afternoon rally with more than 2,000 attendees was underway. The rally was sponsored by yet another newly formed group, the Peace Union, whose members wore yellow armbands, intent on counteracting the image of student violence from the previous days. A spokesperson set the tone for this rally: “We will not break windows, we will not yell and chant, we will light candles and peacefully protest.” Not all in the crowd were in sync, though, as junior Julie Jensen, ’74 EDU, warned, “I am not going to be non-violent. If I am arrested I am going to resist.”[16]

Later that evening, a huge crowd of 10,000 students and faculty gathered peacefully on the Quad, facing the Auditorium steps for a candlelight memorial service to honor the four slain at Kent State and Edgar Hoults. Nine hundred guardsmen stood nearby. A Catholic priest from the Newman Foundation prayed for understanding. A McKinley Foundation minister led the students in a litany to “affirm a new way.” A rabbi from the Hillel Foundation urged the students to rededicate themselves to the sacredness of life.

Not all protests were marked by violence. Some student groups, such as the Peace Union, held candlelight rallies. (Image courtesy of UIAA Photo Archives)

In the crowd, yellow armbands mingled with red ones, the latter worn by those rejecting nonviolence, one of whom warned, “You’re going to be talking about nonviolence when they take you to Auschwitz.” Another offered, “You get the National Guard to wear yellow armbands, then we’ll be non-violent.” Debbie Senn, ’70 LAS, MA ’78 LAS, a Strike Committee coordinator, urged both groups to “get together and work to make the strike a success.” Ed Pinto, ’71 LAS, newly elected undergraduate student chairman, announced that 37 percent of all classes had been cancelled by the second day of the strike and that approximately 90 percent of Illinois students were honoring the strike. He expressed optimism that the strike would be virtually 100 percent effective by the third day. The participation rate of the Illinois strike was high but not unique, as the National Student Association declared the strike a nationwide success, with 437 of the nation’s 1,500 colleges, nearly 30 percent, on strike or closed outright by end-of-day Thursday.

Following Pinto’s speech, visiting professor Parenti, who was released from jail only hours earlier, spoke to the crowd. Dramatically, Parenti offered that “it isn’t so bad to get arrested, and maybe it isn’t so bad to die when our cause is just…one day we will be able to tell our children that in the moment of truth, we fought for social justice, and did not give our lives to the tawdry pursuits of gadgets and gimmicks and houses in the suburbs.” He closed his speech, fist in the air, shouting, “The future is ours,” and his audience rose and cheered loudly.[17]

Thursday had been a day of decision for Chancellor Peltason. College presidents across the nation were determining whether or not to close their schools to avoid violence. Preparing for the worst, Peltason had written a draft statement, directing the shutdown of his campus.

But in the end, he chose not to issue this statement. (It is now available in the University archives with a handwritten note at the top, “Draft by Peltason 5/7/70—not used.”)

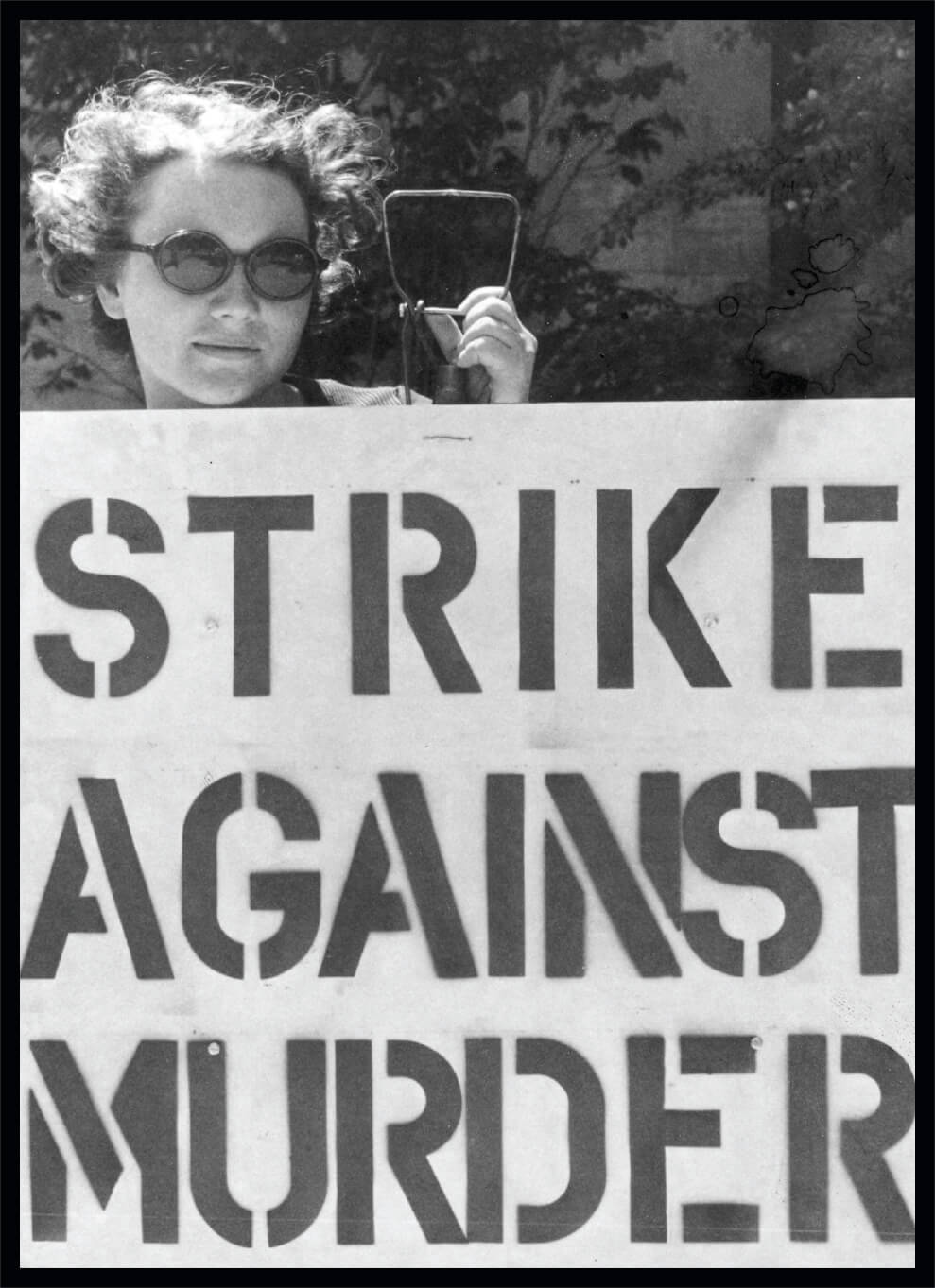

The Illinois strike, which ran from Wednesday, May 6, through Friday, May 8, succeeded at emptying most classrooms and freed thousands of students to express their frustration and anger toward the government and, by proxy, their University. (Image courtesy of UI Archives)

With Peltason’s decision to keep the University open at all cost, the final day of the strike, Friday, began with nervous anticipation on all sides. It would prove to be a day of turbulence. The day started on an upbeat note for the strikers when the College of Engineering, one of the more conservative units on campus, held a public meeting of students and faculty on the lawn of the EEB and voted to officially support the strike, following the lead of most other departments. But trouble developed later when a large crowd of more than 2,000 students, attempting to block the University’s Central Receiving Depot on the southwest edge of the campus, formed a peaceful picket line to try to prevent delivery trucks from entering. Soon, University police appeared, and with state troopers, cleared the students out of the road, allowing teamster drivers, much to the students’ dismay, to cross the now broken picket line. At the end of the day, Governor Ogilvie ordered the remainder of his National Guard reserves to report for duty, bringing the total of guardsmen stationed at Illinois colleges to more than 9,000. In effect, the entire Illinois National Guard was now guarding the state’s university system from the state’s university students.

At the end of the week, the U of I Strike Committee declared the week’s action a complete success, announcing 97 percent effectiveness by the final day. The committee reported that classrooms on the side of the Quad that were home to the humanities, languages and social sciences were virtually deserted the entire three days. On the engineering campus, buildings had been more populated, but many of the classes were empty or cancelled. In buildings that housed the mining and metallurgy, physics and commerce departments, Altgeld and David Kinley Halls, the committee claimed that fewer than half of the classes were meeting, and those had but a handful of seats filled.

President Henry issued a statement Friday evening. Perhaps encouraged by his impending retirement, which he had announced earlier in March, he stated a public position on the Vietnam War. This unprecedented action, speaking out even mildly against the nation’s foreign policy, was only warranted, Henry said, because of “the present situation on the campuses of the nation and the interaction between public issues and University affairs.” After years of refusing students’ requests to do so, Henry finally and publicly stated, “I personally deplore the war in Southeast Asia, and I hope for its early conclusion. I believe the objective of ‘victory’ is wrong…. I join all of those who would bring the fighting to a close as expeditiously as possible.” After years of entreaty and demands by his Illinois students, the mild-mannered, diminutive administrator had finally conceded and supported their position: “I respect the depth of feeling and the interests of our students whose generation is fighting this war and who will live their lives with the results of it,” recognizing that “casualties of the war, at home as well as overseas, have already marred our future.”[18]

Peltason also issued a statement late Friday, jointly with nearly 100 of his vice chancellors, deans, department heads and directors. Although lining up behind Henry, the chancellor, with dire words, would repeat his steadfast, stubborn dictum that the University must stay open: “The universities of these United States face their greatest crisis in the life of this republic.” Like Henry, he too finally gave in to his students’ request of many years and took a public stand against the war: “We too believe the Indochina war must be brought to an early end before it tears this great nation apart.” With a nod to the killing of Hoults, he added, “We too deplore the tragic deaths at Kent State and in this community…. We share concern over injustice and racial prejudice wherever it exists in society.” But the chancellor could not stop himself from once again arguing that “no attempt be made to coerce those who wish to attend classes, and that no efforts be made to impede University operations.” The chancellor ended by quoting The New York Times editorial of the day, conveniently supporting his position, which criticized those higher-education institutions that had chosen to support their striking students:

“The best way that the academic community can demonstrate that there are civilized roads to a more responsible society is to stay open and concentrate on the effective harnessing of ideas to action. The irrationality of escapism is no answer. That only leaves the field to the Philistines.”[19]

However, any hopes for “orderly inquiry,” “rational discourse” and a “more responsible society” would be dashed on this weekend, as more Philistine-like attitudes would prevail. Weather reports for Saturday called for a chance of showers and thunderstorms; in fact, there would be plenty of thunder, and eventually showers, too. A special Sunday edition of the DI, published not on newsprint but on standard 8-1/2 by 11 mimeograph paper and run off at a local co-op print shop, would tell the story of the tumultuous weekend to those few Illini who did not personally witness the events. These were extraordinary times, as the paper’s makeshift masthead demonstrated.

The final days

Throughout the three days of the spring strike, with sunny weather and mild temperatures and no classes to attend, groups of students would loosely form, disperse and re-form throughout the campus and especially on the Quad. Saturday’s planned activities included a wide variety of workshops and teach-ins on the Quad—on the Illiac IV project and University complicity in the war, on the evils of campus ROTC and the upsides of cooperatives, on communal living, underground newspapers, women’s liberation, self-defense and communist Cuba. Live music was to begin at noon, followed by the Illiac IV rally. Planned speakers included Lee Weiner, ’72 LAS, of the Chicago 8, and Linda Quint and Nick Ridell of the Chicago 15 (another group of antiwar protesters with a trial underway in Chicago), all to be followed by a protest march to the Illiac IV site.

The predicted showers held off Saturday and a sometimes festive, sometimes riotous spirit was in the air as thousands of students hung out across the campus enjoying the weather. The peaceful “Illiaction” rally drew a crowd of thousands. But the mood didn’t last, as following the rally a long, chanting line of students began the march from the Quad toward the Illiac IV construction site, walking in the middle of city streets, leaving blocked traffic in their wake. However, the march never made it to the planned destination. Once again, a few protesters began throwing rocks at windows along the way, and then, at Wright and Green, the crowd came to a stop and blocked the intersection, some marchers sitting down, in an attempt to hold the intersection, until Champaign’s Chief Shirley arrived, personally warning them on his megaphone to clear the streets or face arrest. Soon, eight were in custody and the intersection was cleared, but large crowds of students continued to mill restlessly on campus streets and the Quad throughout the afternoon.

Despite the student-led strike boycotting classes and a large contingent of guardsmen and Illinois state troopers, Chancellor Peltason didn’t close the University during the week of May 4. (Image courtesy of UIAA Photo Archives)

Then, around 6 p.m., with no warning, state police, with guardsmen in support, disembarked from buses on Green Street and began an unexpected sweep south, through and around the Illini Union, tersely gathering up groups of students, pushing and shoving them toward the Quad. More state troopers appeared on the sides of the Quad, surrounding the now confined students. Then, with neither warning nor explanation, the troopers abruptly began arbitrarily grabbing individual students, making arrests and loading their captives onto three large buses waiting nearby. State police made more than 100 seemingly random arrests.[20]

The buses filled and rolled away; the arrested students were held in the Great Hall below Memorial Stadium before being transferred to police stations for formal arraignment. The troopers and guardsmen then moved off the Quad and left campus. The surprising, unexplained arrest sweep left thousands of shocked and angry students behind on the Quad.

Trouble erupted again at 8 p.m., when someone pulled a fire alarm in the Illini Union and minutes later a University employee called police to quell a separate disturbance at the candy counter. Instead of police, state troopers responded and again began roughly moving all students out of the Union and onto the Quad. What little patience the troopers had was likely exhausted by a few students responding to the rough tactics by “smashing glass, overturning ashtrays and setting fire to a sofa.”[21] After clearing the building, the troopers departed the area again. At 8:30 p.m., about 1,000 of the crowd began a march from the Quad to Memorial Stadium to demand the release of those students arrested earlier, stoning police cars and smashing windows on the way. Those who remained behind roamed the quad, damaging Altgeld Hall, the Administration Building and any other targets they could find.

At 10 p.m., the state police returned to the campus, along with 750 National Guardsmen, both groups pelted with rocks by angry students upon their arrival. The guardsmen surrounded the Quad and slowly cleared it while troopers charged up John Street, swinging their riot sticks and clearing the streets. Other police then moved up Sixth and west on John Street to clear those areas, making arrests along the way. Slowly, the entire campus area was cleared by the overwhelming joint force of state troopers, guardsmen and local police. Finally, around 11 p.m., the predicted heavy rain at last began to fall, forcing the few remaining diehard students to seek cover. By 11:30 p.m., the Quad was deserted, and with this rainy, confusing Saturday night, the violent phase of the Illinois student protest movement quietly and unexpectedly spluttered to an end.[22]

Aftermath

Chancellor Peltason, like many of his generation, maintained that the “student unrest” of the ’60s was inexplicable, that no one knew why it happened. Looking back from 50 years on, it’s not a mystery. The ’60s student protest movement happened because a significant segment of a generation, when confronted with a moral challenge, exercised agency, acted independently and demonstrated free will in the face of overwhelming opposition and thus affected history. Their movement was inspired by forces of the era: black Americans rejecting oppression, colonial peoples throwing off empire and an Asian David bloodying a western Goliath.

The students and their movement were very much of their time, and those who lived through the time cannot easily forget. That may be the most enduring lesson of the ’60s—that those who lived through the decade, and those who hear of it or read of it, will remember and know that in the arc of history, when conditions arise, when stars align, when the times demand, it can happen again.

1. Carl Schwartz, “Department of Defense to Employ UI Computer for Nuclear Weaponry,” The Daily Illini, Jan. 6, 1970, pg. 1

2. Kathy Reinbolt, “Spock Justifies Revolution,” The Daily Illini, Feb. 25, 1970, pg. 3

3. “Police, Protesters Clash in Fighting over GE Recruiting,” The Daily Illini, March 3, 1970, pg. 1

4. “Police, Youths Clash; Cities Impose Curfew,” The Daily Illini, March 4, 1970, pg. 1

5. Earl Merkel, “300 of Guard Used in Campus Disturbances,” The Daily Illini, March 4, 1970, pg.1

6. “Nine Students Suspended in Third Night of Disorders,” The Daily Illini, March 5, 1970, pg. 1

7. Roger Simon, “Up Against It,” The Daily Illini, March 10, 1970, pg. 8

8. “Quiet March Protests Killing,” The Daily Illini, April 30, 1970, pg. 1

9. “Death Sparks Violence in Cities,” The Daily Illini, May 1, 1970, pg. 1

10. “Nixon Says No Invasion,” The Daily Illini, May 1, 1970, pg. 1

11. G. Robert Hillman, “Policeman Relieved of Duty after Edgar Hoults Shooting,” The Daily Illini, May 1, 1970, pg. 1

12. “Four Kent Protesters Dead,” The Daily Illini, May 4, 1970, pg. 1

13. Ellen Asprooth, “Vandalism Follows UI Strike Call,” News-Gazette, May 6, 1970, pg. 3

14. “Nixon: A Presidency Revealed,” television program, History Channel, dir. Joe Angio (Feb. 15, 2007)

15. Todd Gitlin, The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage, pg. 410

16. Barbara Demski, “2,500 at Peace Union Rally for Non-violent Protest Here,” The Daily Illini, May 8, 1970, pg. 1

17. Ellen Asprooth, “Parenti Comes Close to Bringing Crowd Together,” News-Gazette, May 8, 1970, pg. 19

18. “Dr. Henry Explains,” News-Gazette, May 9, 1970, pg. 1

19. Chancellor’s statement, May 8, 1970, Office of the Chancellor, subject file 1967–80, University of Illinois Archives, Urbana

20. “102 Arrested,” The Daily Illini, May 10, 1970, pg. 2

21. Terry Michael, “105 Arrested on Campus,” News-Gazette, May 10, 1970, pg. 1

22. “102 Arrested,” The Daily Illini, May 10, 1970, pg. 2

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michael V. Metz, ’70 LAS, participated in the student protest movement at the University of Illinois from 1965 to 1970. He retired from a career in high-tech marketing and resides in Saratoga, Calif.

Michael V. Metz, ’70 LAS, participated in the student protest movement at the University of Illinois from 1965 to 1970. He retired from a career in high-tech marketing and resides in Saratoga, Calif.

Copyright Permission: Excerpted from Radicals in the Heartland: The 1960s Student Protest Movement at the University of Illinois by Michael Metz. Used with the permission of the University of Illinois Press. Copyright 2019 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois.

Point, counterpoint

An oral history

Compiled by Ryan Ross

“I stayed in my sorority. A lot of kids didn’t and the Greek system kind of suffered. But we changed our focus, and we felt we had to support those of us who weren’t lucky enough and wound up over in Vietnam. We felt that we owed them something. And the least we could do was to organize protests and to show the powers that be that we cared about this country and that we were going to question authority. Sometimes it got ugly. The Dow Chemical protest was about as ugly as it got. So, yes, we were political, and we were proud of it. But I think, after all, we’re Fighting Illini. We can’t just be passive and say we don’t care about such things. So as I said, it was big, it was a sea change. But I was proud of that generation, and very proud to be a part of it.”—Carolyn Sharp Kelley, ‘71 LAS, MA ‘72 LAS, Lincoln Hall Storyography Project (2010)

“A deplorable stain on our university’s reputation.”—Bob Kjellander, ’70 LAS, MA ’72 LAS, president of the Young Republicans, News-Gazette (March 4,1970)

“We want the University to take a positive step to help the situation in our community and in the world. It’s time people looked beyond the occasional violence and begin to examine the reasons behind the students’ actions.”—Ed Pinto, ’71 LAS, chairman of the Undergraduate Student Association, News-Gazette (May 8, 1970)

“The largest group of students was not in the anti-war movement. It is a current misconception to believe that most students were in the anti-war movement. The majority was too busy going to college.” —William Bates, ’71 MEDIA, oral history with Student Life and Culture Archives

“In Fall 1968, I was a sophomore and lived in Garner Hall, a student dorm. Two black students lived on our floor. One, Paul Chandler, was stuck living in the rec room at the end of the hall, as they had not designated enough rooms for the black students. He became president of the Black Student Association and was involved in a sit-in at the Illini Union where a large number of black students were arrested. After this, a few hundred white students formed a group called Students Against Racism in support of the Black Student Association. Soon after that, I also joined the anti-war movement and worked for The Walrus, an underground newspaper. I spent much of my time at meetings and demonstrating. Somehow, I still managed to graduate from the U of I in 1972.”—Phil Strang, ’72 MEDIA, interviewed by Ryan Ross (Dec. 9, 2019)

“We hope for nothing, we demand everything.”—Black Student Association motto, 1966

“I would like to suggest an anti-moratorium demonstration to the concerned good ol’ American students (the silent majority) at the University as a means of displaying their righteous outrage at the pinko-hippie-radicals and their no-good attempts to disrupt the functioning of the wonderful University.”—Ron (America First) Brown, letter to the editor, The Daily Illini (Oct. 15, 1969, p. 10)

“In conscience, I can no longer strike. Wednesday as I walked among my fellow students, watching and listening, one question kept recurring: Why are we striking?

“The escalation of the war into Cambodia and the tragic deaths at Kent State appear to be the issues at hand. Yet again and again, I become more befuddled as local political issues are introduced, which once more, draw support away from the student action on a national level.

“The present strike is in protest of American military action in Cambodia as well as in reaction to the Kent State tragedy. In order to remain an effective political action, I feel the strike must focus only on these two issues. The introduction of Illiac IV, ROTC and recruitment may cause students who, now, are deeply involved, many for the first time in their lives, to become confused and restless.

“Even worse, by obliging these students and implicitly standing for demands with which they do not necessarily agree, they may disengage themselves from any further political action.

“It is precisely this result we cannot tolerate if the power behind national student unity is to influence American political policy.” —Virginia Tenzer-Ballard, ’87 LAS, letter to the editor, The Daily Illini (May 9, 1970)

“Your GPA kind of paled in comparison to the life-and-death struggles people were facing.”—Michael Real, PHD ’72 MEDIA, Illinois Quarterly (July/August 1995, p. 24)

“It was a time of open expression and verbal confrontation. Because of that, the Free Speech Area was established near the Illini Union. The opinions may have been callow, unformed, immature and unyielding, but students expected them to be heard and respected. In many cases, they were not. The war in Vietnam, with its doublespeak, half-truths and various invasions, incursions and promises of peace, created a large campus population of cynics and protesters. And bit by bit, everything was affected.”—Natalie A. McNamee, ‘69 LAS, letter to the editor, Illinois Quarterly (September/October 1995, p. 5)

“We need to show that we are competent, that we are intelligent. This is not the image of students reflected in newspapers and television. Unless someone is throwing rocks, the reporters turn around and go home. … I balance everything on a scale. If it looks like boycotting classes is the right thing, will accomplish something, I’ll do it. If you want nonviolent strikes, you get nonviolent people.”—Barbara Delake, Champaign-Urbana Courier (May 10, 1970)

“Those kids who did the damage couldn’t give a flying fling who pays for it.”—Don Ruhter, ’69 MEDIA, MS ’73 MEDIA, News-Gazette (March 3, 1970)

“The [National] Guard and the police aren’t the main issues. They were called here and perpetrated violence on this campus because we were striking over certain pressing issues. Those issues have not been resolved, and the strike must continue.”—Debbie Senn, ’70 LAS, MA ’78 LAS, student strike leader, Champaign-Urbana Courier (May 11, 1970)

“I was a sophomore in electrical engineering in the spring of 1970. There were two events that I remember well because both affected the Electrical Engineering Building [EEB—now Everitt Laboratory]. I had a new camera and was able to record images that still astound me today. In March 1970, there were armed guards placed at each door of EEB. I was never stopped when I entered the building. The joke was that if you were carrying a slide rule they let you in. In May 1970, armed members of the Illinois National Guard lined the north side of Green Street from Matthews Avenue to Wright Street to protect the engineering campus from any threats from south of Green Street. Many of the National Guard were actually the same age or younger than the students.”—Michael VanBlaricum, ’72 ENG, MS ’74 ENG, PHD ’76 ENG, interviewed by Ryan Ross (DEC. 19, 2019)

“I’ve been working for 10 years on my doctor’s degree, and I’m not going to let them destroy it now.”—John Westfall, on fighting with protestors outside the Administration Building and helping the police, March 2, 1970, News-Gazette (March 3, 1970)

“There was a rethinking of the entire value system of the time. … I remember people spending all night in the GSA [Graduate Student Association] office, running off signs and T-shirts and posters saying ‘Strike.’ It was terribly depressing that things had reached such a point. There was a feeling that the war had come home.”—Michael Real, PHD ’72 MEDIA, Illinois Quarterly (July/August 1995, p. 24)

“Some students, myself included, were revolted by the protest chant, ‘Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Minh! NLF (National Liberation Front) is gonna win!’ And sometimes we used to imitate some of the protesters: ‘C’mon people, we’ve got to get together!’ But a lot of common sense prevailed. I think it was a dark period in our nation’s history, yet our university came through it pretty well. It was odd. It was not what you thought your college experience was going to be like.”—Paul Ingrassia ’72 MEDIA, Illinois Quarterly (July/August 1995, p. 24)

“My wife Barb and I were down in Champaign visiting Larry, ’69 ENG, MS ’71 ENG, PHD ’75 ENG, and Jane Weber, ’69 LAS, in May 1970. Barb and I had graduated the year before. The four of us walked over to Green Street near the Alma Mater to observe the protest. We were on the north side of the street when the action started. As I recall, there was some shouting. Someone in front of us turned around and took our picture. Larry told us that the person taking the picture was his lawyer, who he obtained when Larry had been arrested for protesting recently. The lawyer said the picture was to prove that Larry was on the north side of Green and not in front of the Alma Mater. We observed a bus arrive, hastily loaded with what appeared to be state troopers. The bus stopped abruptly, and the troopers came running out with clubs, ready to swing. They headed towards the people on the south side of Green Street. That is when the four of us left. My thought at the time was—the people on both sides of Green Street are acting the same. Why did those on the south side get the clubs? Later we heard that many on the Quad were arrested.”—Russ Seward ’69 LAS, MA ’72 LAS, interviewed by Ryan Ross (Dec. 3, 2019)