We Reach Millions

Throughout the 1930s and ’40s, local college and high school students acted in the radio drama WILL Playhouse, one of the station’s most popular original programs. (Image courtesy of Illinois Public Media)

Throughout the 1930s and ’40s, local college and high school students acted in the radio drama WILL Playhouse, one of the station’s most popular original programs. (Image courtesy of Illinois Public Media) Editor’s note: The WILL audience stories that appear in this article are composites, based on information from the following sources: interviews with WILL listeners/viewers and staff; the Illinois Public Media archives; The Daily Illini; Patterns magazine; and the University of Illinois Archives.

It was April 6, 1922, a time of Model-T Fords and movie palaces, stock market booms and bootleg gin, and in a long, high-ceilinged room on the Urbana campus, the U of I took one more step into the modern age.

That evening, a Thursday, an eager crowd gathered inside the electrical engineering laboratory, spread out between rows and rows of desks and equipment, ready to be amazed. They were there to witness magic. What they saw instead was the future.

By 8:30 p.m.—show time—everything was in place: the wires double-checked, the transmitter switched on, the mic hot and live and ready to go. F. A. Brown, of the Electrical Engineering Dept., raised a hand to silence the crowd, picked up the receiver and spoke.

The University was on the air.

It was the first broadcast of WRM—for “We Reach Millions”—the U of I’s experimental, non-commercial radio station, and it reached listeners from Urbana to Pittsburgh, Toronto to Tulsa, Memphis to Kansas City.

Six years later, WRM would change its name to WILL—call letters that are now as familiar to central Illinoisans as corn fields and Cubs fans.

WILL: call letters that are as familiar to central Illinoisans as corn fields and Cubs fans.

Over the next century, WILL would expand from radio to television and the Internet, serve as the University’s home for National Public Radio (NPR) and the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), and evolve into a trusted source for news, music, entertainment and educational programming. In the process, it would become a meaningful part of daily life for millions of people all over Illinois, season by season, year after year, often over a lifetime.

This is the story of WILL, told through the eyes and ears of that dedicated audience, who have tuned in to listen, watch, learn and grow for the past one hundred years.

News and public affairs coverage has long been a WILL hallmark, from the national voices of PBS and NPR to the local personalities of Illinois Public Media. In the 1960s, WILL’s charismatic news director, Henry Lippold (above), became a local institution as the station’s nightly news anchor. (Image courtesy of Illinois Public Media)

In a salmon-colored kitchen in southwest Champaign, it’s 5 a.m. on a Thursday morning in May. A retired engineer pours himself a cup of coffee, opens the dining room curtains and tunes his radio to Morning Edition on WILL-AM 580. He’ll sit at the dining room table with his coffee, to watch the sun rise and listen to the show, as he’s done nearly every weekday morning for the last four decades.

Like many devotees of WILL, he grew up watching and listening to the station with his parents. Throughout his childhood in the 1950s and ’60s, WILL was a near-constant presence in their home: Illini basketball games on TV and radio in the winter, Illini football in the fall and, almost every night, without fail, the local newscast with Henry Lippold—full of energy, near-bursting to report the stories of the day.

It’s been more than 50 years now since WILL stopped covering Illini sports, but that’s still the first thing he thinks of when he hears the call letters—all those hours in the family Oldsmobile, driving with his father to places near and far, announcer Lon Kramer on the horn from Memorial Stadium or Jim Turpin, ’61 LAS, from the Assembly Hall.

He’s also reminded, most nights, of Henry Lippold, when he sits down to dinner and flips on the PBS NewsHour. The NewsHour is every bit as good as the newscast from his childhood, and better in many respects. Still, it’s almost too polished, lacking the homemade quality of Lippold’s show, as well as the obvious passion Lippold felt for reporting the news that made every broadcast feel like an event.

As a child, WILL was something that helped the engineer feel close to his parents. As an adult, it’s his lifeline to informed citizenship. When he listens to Morning Edition and other NPR News shows, like 1A and All Things Considered, he feels like he’s taking an active role in democracy—that he’s getting the information he needs to vote responsibly and to make sound arguments about issues that affect us all.

And when he hears homegrown news programs like The 21st, reads online stories from WILL’s Illinois Newsroom or watches Channel 12’s live candidate debates during election years, he feels proud that his monthly donations are being put to such good use.

“C” is for cookie…and children’s programming. For more than 50 years, WILL has been a home for Sesame Street and other PBS favorites, such as Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood and Curious George. (Image courtesy of Illinois Public Media)

Now it’s 6 a.m. across the viewing area, the sky a mix of Illini orange and blue, and throughout central Illinois preschoolers are straggling out of bed, their blankets trailing behind them, Linus-like, as they walk to their living rooms to start the day as they always do, with PBS Kids on WILL-TV. They’ll stop by the kitchen to get some Oatmeal Squares from the pantry, then snuggle up on the couch and watch until it’s time for their parents to go to work, Molly of Denali through Curious George. Then they’ll do it all over again tomorrow.

A form of that ritual has been taking place for more than 70 years. Back in the 1940s, those preschoolers’ great-grandparents were sitting in front of their giant Zenith radios like trained wolfhounds, listening to children’s programs such as Stories ’n’ Stuff—one of the many original shows WILL created in the decades before PBS (1970) and NPR (1971) hit the airwaves.

A generation later, with the Vietnam War hovering wraith-like over the evening news, those radio fans’ children spent their afternoons watching Sesame Street and The Electric Company on Channel 12, rabbit ears on their TV sets, avocado-colored appliances in the background.

Children of the ’80s and ’90s plopped down on the couch for Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood and Reading Rainbow, Pop Tarts in hand. And kids today watch Wild Kratts and Odd Squad, sometimes on television, and sometimes on tablets, laptops and smartphones, no matter where they go.

This history is lost on the four-year-old watching Nature Cat in the back of the family minivan, but little does she know that she is part of a rich, educational tradition that will continue long after she’s grown.

Hours of classical music, opera and jazz played by enthusiastic, unforgettable DJs—that’s what WILL-FM 90.9 is all about. Popular hosts such as Vic Di Geronimo (pictured) and John Frayne have become like dear friends for generations of listeners. (Image courtesy of Illinois Public Media)

It’s 10 a.m., and an Urbana store owner is just opening her shop. As the first patrons of the day filter in, she takes a stool behind the counter and turns on the radio: WILL-FM 90.9. It’s been the soundtrack of her shop since at least the mid-’70s. And while the DJs have changed over the years, some of them dearly missed, the music has not: classical, opera, a little jazz—compositions that get you through life, one bar at a time.

Today, she and her patrons have the pleasure of hearing Classic Mornings with Vic Di Geronimo until noon, then Afternoon Classics till closing time: everything from Byrd to Britten, with incisive commentary and biographical notes about the composers that make every program both a concert and a history lesson of the highest order.

On Fridays, when the store stays open late, patrons will have the added bonus of Prairie Performances with Roger Cooper, MMUS ’78, a long-running spotlight for local orchestras and quartets—the music made even more dramatic and beautiful by Cooper’s introductions, his bass-drum voice an opening act in itself.

On Saturdays, the last and busiest day of the workweek, the owner listens to John Frayne’s Classics of the Phonograph, followed by Afternoon at the Opera. She sits there on her stool, surrounded by Verdi, Rossini and the comfort of her shop. There are worse ways to spend a life, and she knows it.

People who work in radio or television will tell you that everything depends on the clock—the broadcast schedule. And until recent years, that was equally true for the rest of us. If you wanted to watch a show that aired on Tuesday night at 8 p.m., you arranged your schedule around it (or taped it with your VCR or, later, DVR). If you wanted to listen to a radio show, you tuned in when it was on or you missed it.

But in our smart-phoned, app-owned, streaming world, if you want to watch or listen to something on your own time, no problem. It is no longer possible to miss a show on Tuesday night and wonder if you’ll ever have a chance to see or hear it. You’ll just look it up on a streaming platform and tune in later.

Like other media organizations, WILL’s parent company, Illinois Public Media (IPM), continues to adapt to this changing world, as does its audience.

Imagine that it’s the noon hour. Whether you’re back in the office after a long pandemic interlude or you’re still working from home, if you take a break and walk outside, there’s a good chance that you will see someone who is listening to an NPR podcast on their headphones—a program that, once upon a time, they would have heard only on their local NPR station.

Like his grandfather and father before him, the farmer tunes in to WILL’s agriculture programming throughout the day.

On campus, an undergrad walks across the Main Quad, listening to last week’s episode of The Treatment with Elvis Mitchell. In Decatur, a crop scientist listens to WILL’s local news podcast, 217 Today, on her drive to the fields. In Kankakee, a pharmacist fills orders as she works her way through the last few episodes of Hidden Brain. And in New York City, a stand-up comedian walks through Washington Square Park, listening to the newest Radiolab, a show he first heard as a chemistry major in Urbana.

Elsewhere, at other times, in other places, people are using streaming platforms to watch TV programs that they traditionally would have watched on Channel 12.

In Chicago, an advertising copywriter originally from southern Illinois watches WILL’s new documentary about county fairs on IPM’s website. In Bloomington-Normal, a U.S. history teacher uses the PBS app to show Ken Burns’ The Civil War to her 8th graders. Somewhere on I-57, a six-year-old watches Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood on his iPad in the backseat of his mother’s car. And on and on.

Still, there are plenty of people who listen and watch as they always have, by tuning in to WILL. While that student walks across the Quad and the pharmacist fills her orders, the store owner in Urbana eats her daily ham-on-rye in her shop, with Vivaldi in the background, and the retired engineer drives to Sun Singer in Champaign for lunch, his car stereo tuned to AM 580, Here and Now in full swing.

And so it will continue, as new technologies and new forms of broadcasting develop, now and in the future.

An hour south of campus, on a stretch of good bottomland in Cumberland County, it’s just after 2 p.m., and a longtime farmer in a Pioneer ball cap is tuning his tractor’s radio to AM 580. He has been listening to WILL virtually all his life, starting when he was a kid, helping his dad and grandfather around the machine shed. They would listen to whatever was on while they worked—music shows, campus news, World’s Best Short Stories—but whenever the ag reports began, work stopped, and afterwards his dad would explain what they’d heard. It was all a part of his education.

The explanations never came from his grandfather, a man of few words and few outward emotions who hardly said more than “hand me that, would you?” or “humph” about something he heard on the radio.

But his grandmother loved to talk, and in the evenings she would tell him stories about what life was like when his father was young. He remembers her saying (again and again, as she got into her 90s), how important it was when the family got a radio back in the 1920s, a crystal set from the Sears catalog, the only kind they could use before they had electricity at the farm.

His grandmother told him what WILL was like in the early years, when it called itself “The University of the Air”—live music from string quartets; students acting in radio dramas; professors lecturing on everything from agriculture to architecture. She told him about how she sat there on her porch and discovered the outside world, one program at a time.

But that was all long ago.

Today, like his grandfather and father before him, the farmer tunes in to WILL’s agriculture programming throughout the day—the Opening Market Report at 8:55 a.m., the Market Update at 10:58 a.m., the Midday Market Report at 12:58 p.m., the Closing Market Report at 2:08 p.m. and the Grain Market Report at 4:32 p.m.

He also looks forward to Commodity Week on Fridays at 2:30 p.m. and has come to think of its host, Todd Gleason, ’86 ACES, as a trusted colleague. And it’s no wonder: Gleason has been hosting ag programs on WILL for more than 30 years—not only market reports and analysis, but also interviews with Illinois farmers and agricultural specialists, live and literally “in the field.”

The farmer feels like he can rely on Gleason, and he rarely misses a show. Some years, he even travels to the in-person “ag outlook” meetings that Gleason and his now-retired co-host Dave Dickey, ’88 MEDIA, began organizing in the 1980s. But mostly, he tunes in to check on the markets. And occasionally, in the middle of the report, he’ll think of his grandmother’s stories about the early days of radio, his grandfather listening to Extension programs on the front porch, and he’ll feel a sense of rootedness—a connection to the past—and he has WILL to thank for that.

Talk shows such as Focus 580 and The 21st have been among the highlights of WILL’s original programming, with probing conversations between their iconic hosts and a world’s worth of guests. In 2013, Illinois Pioneers host David Inge (left) walked down memory lane with the legendary men’s basketball coach Lou Henson. (Image courtesy of Illinois Public Media)

Only a few miles away from the farmer, on a pitted country road in Coles County, it’s 3 p.m. and a seasoned mail carrier is tuning in to Fresh Air with Terry Gross. Like many people who spend all day in their vehicle, she has come to view the radio as a friend. AM 580 has been the best thing about a job that often feels lonely, and Fresh Air’s interviews make her feel connected to the wider world.

Thirty years ago, when the mail carrier was starting her job, she faithfully checked the weather reports—“neither snow, nor rain, nor heat,” and so on—and quickly decided that the best meteorologist in the area was WILL’s Ed Kieser. He had a great sense of humor, and his reports managed to be both informative and delightful. She became such a big fan that she started donating money to the station and, every so often, she even drove an hour to campus—after driving all day on her route—to attend his “Tornado Talk” lectures.

In those years, the mail carrier also became a dedicated listener of two popular local programs: an unpredictable, we’ll-try-anything brand of call-in show, Focus 580 with David Inge, MS ’84 MEDIA; and the varied and always interesting Afternoon Magazine with Celeste Quinn, ’80 LAS. Both programs featured warm and intellectually curious hosts, and she often thought of them as kindred spirits. And it’s no wonder: Inge and Quinn were husband and wife.

These days, because of seniority, the mail carrier no longer delivers her route on Saturdays. But back then, there she was, up-and-at-’em with the dawn, while her family slept in and enjoyed their weekend. Fortunately, WILL’s Saturday programming made the burden a little easier, with NPR comedy shows such as Car Talk, travel programs with Rick Steves and storytelling hours like This American Life.

AM 580 has been the best thing about a job that often feels lonely.

She would come home in the evenings, Monday through Saturday, and talk with her kids during dinner about everything she’d learned on WILL that day. For them, WILL was a firmly ingrained part of their lives. From a young age, they had been watching kids’ shows, Julia Child and The Joy of Painting with Bob Ross on Channel 12—all those “happy little trees”—and half-paid attention while their dad watched home improvement shows like This Old House. (They liked Bob Vila’s beard.) Sometimes in the evenings they’d watch old movies on Silver Screen and learn about them from host Thomas Guback, MS ’59 MEDIA, PHD ’64 MEDIA, leading to a lifetime love of Old Hollywood. And on Christmas Day, they would listen to Paul Landis read A Christmas Carol on AM 580, an annual WILL tradition that had started even before their parents were born.

Decades later, they still tune in to WILL, and they still talk with their mom about the things she heard on the radio that day. And they always will.

Now, it’s just before 4 p.m. and a blind woman in Danville is sitting in her paisley living room chair, a sparkling water in hand, waiting for the alarm on her phone to ring. Through the open windows she can hear robins and red-winged blackbirds in her backyard, probably among the apple blossoms, and down the street, the sound of children laughing on their way to the park. She can feel the afternoon sun coming through the windows, and she pushes her chair forward, into its path. Then the alarm trills, and as she presses “stop,” she says, “Alexa, turn on Illinois Radio Reader!”

And just like that, a friendly volunteer begins to read the Champaign-Urbana News-Gazette.

It’s all courtesy of an Illinois Public Media program that started in 1978 as a way to reach an underserved part of the listening audience. For more than 40 years now, Illinois Radio Reader (IRR) has played an important role in the University’s efforts to provide educational services for those with disabilities. Today, IRR’s fleet of volunteer readers supplies more than 80 hours of programming each week, including local newspapers, national publications like The New York Times and even academic journals.

Over and over again throughout the week, the woman in the paisley chair calls to Alexa, and within seconds she’s listening to National Geographic, Harper’s or Poetry Magazine, depending on the day and time.

For many years, she accessed IRR by using a special radio from WILL that was tuned to its frequency, and when she visited friends and family outside its broadcast range, she missed the service terribly. But now that it’s also available online, she can use IRR no matter where she goes, from central Illinois to central Europe—and she does.

“This program was made possible by contributions to your PBS station from viewers like you. Thank you.” How many times have you heard that before a WILL broadcast? Since 1974, the Friends of WILL membership program has helped the station to support its public broadcasting mission through pledge drives (like this one, from 1978) and other fundraising efforts. (Image courtesy of Illinois Public Media)

It’s nearing 7 p.m. and the kitchen’s still a mess from dinner—a glorious black bean soup and tacos made with homegrown vegetables—but the dirty dishes will have to wait. The chef, a librarian by day, grabs a beer from his basement fridge as his wife shouts, “It’s on!” He slams the fridge door and runs up the stairs, and makes it to his recliner before Tinisha Spain finishes her introduction. The show is WILL’s Mid-American Gardener, and since its premiere in 1992 (when it was called Illinois Gardener), it has been a favorite among green thumbs from throughout the growing region.

The librarian has been watching for a decade, ever since he moved into a house in Champaign with a big backyard—perfect for a garden. Back then, the host was Dianne Noland, and each week he would tune in to learn from her panel of local lawn and garden masters, as they answered viewers’ questions about everything from roses to soil quality to those critters that keep eating your sweet corn. He’s often found their advice practical and easy to implement, qualities that make the show a can’t-miss experience for many gardeners.

Several years ago, he and his wife moved to an old farm north of town. One of the first things he did at the new place was to plant a garden, and over the years it has slowly expanded into a behemoth.

The librarian spends hours out there, using the skills he’s learned from a lifetime of paying close attention—to his mother gardening when he was a child, to what he’s read in books and online, to the panels on Mid-American Gardener and to his own experiences with the natural world—and he gives his care and his love to his plants: sweet corn and winter squash, fava beans and kale, garlic and Swiss chard, rhubarb and hot peppers, heirloom tomatoes and dozens more.

And then he brings them inside and makes delicious meals, using techniques he has learned from PBS cooking shows like Mexico: One Plate at a Time, Pati’s Mexican Table, Lidia’s Kitchen and Cook’s Country.

It’s all in a day’s work, he thinks, as he takes a bite of homemade salsa, and he wouldn’t have it any other way.

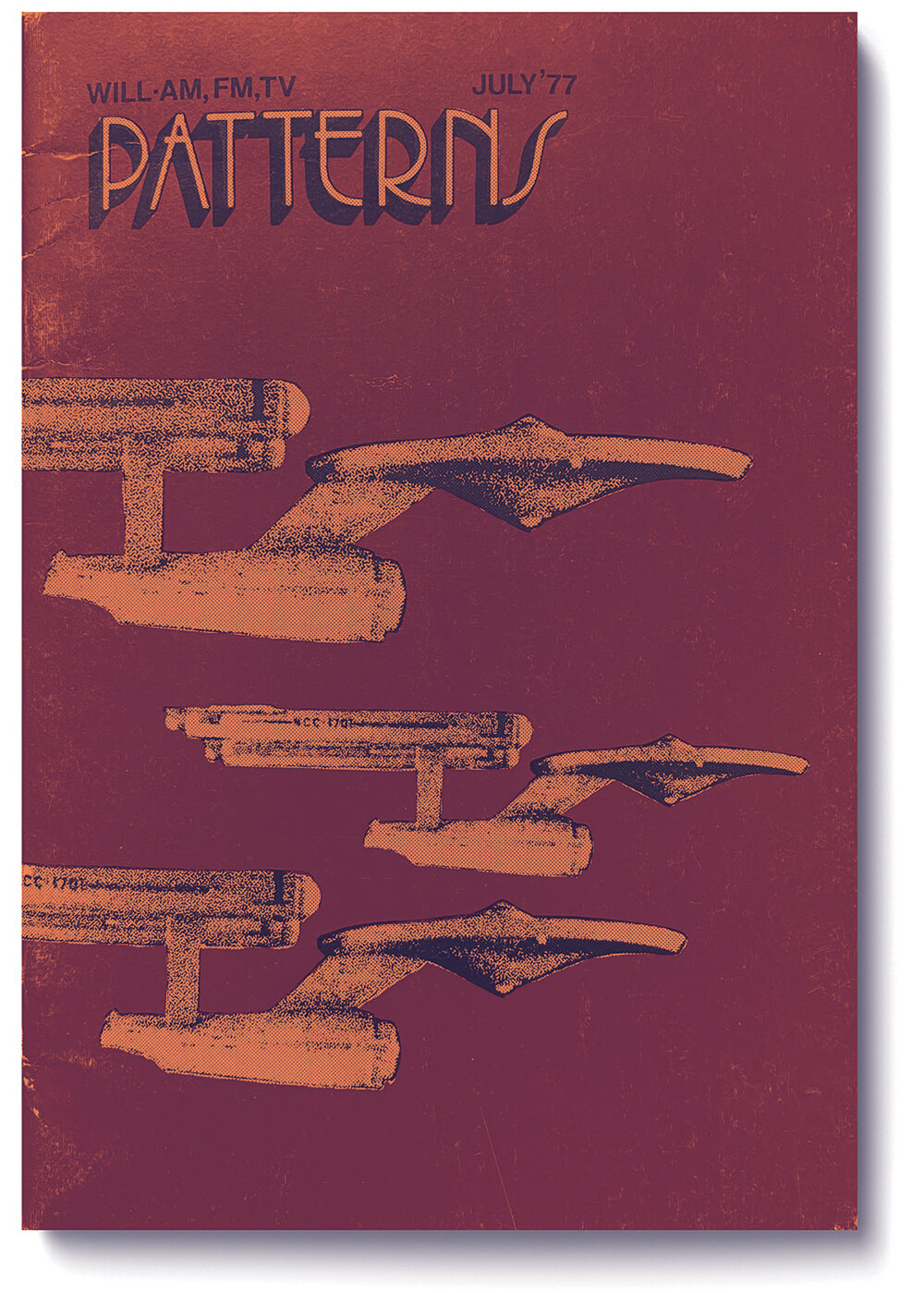

Whether deadly serious or filled with whimsy, WILL’s programming has always offered something for everyone. Patterns magazine, the station’s beloved program guide, helps WILL supporters find the shows that pique their interest. In the 1970s and ’80s, WILL viewers got a weekly helping of Star Trek, among other unexpected delights. (Image courtesy of Illinois Public Media)

Now, it’s 8 p.m., the heart of primetime television, and a children’s author in Homer is tuning in to Father Brown and Wallander on WILL. She has been obsessed with British mysteries, crime shows and Britcoms since she moved to Urbana for graduate school more than 20 years ago, and discovered them on Channel 12. It was like they were waiting for her, and they helped her get through a lonely time, in a new town, in a new part of the country. After a few months on campus, she found that many of her classmates also loved British TV—they were in the English department, after all—and they started getting together at night to watch WILL as a group. They still do that, sometimes, the ones who are left in this transient community.

Every time they’ve flipped on Upstairs, Downstairs or All Creatures Great and Small, they’ve joined a long tradition of WILL viewers who have been tuning in since the early 1970s to watch primetime programming from across the Atlantic—shows like Masterpiece and Monty Python’s Flying Circus that sparked a mania for British TV that is still going strong.

Today, fans of British television have a legion of shows to choose from on WILL. For every Downtown Abbey there’s a Dr. Who, and for every Call the Midwife there’s a Great British Baking Show. Whether the children’s author and her friends are watching who-dunits, who-doctors or who-baked-its, their Anglophile hearts feel as warm as tea and crumpets on a mid-winter’s night.

For every Downton Abbey there’s a Dr. Who, and for every Call the Midwife there’s a Great British Baking Show.

As Father Brown is winding down, it’s 9 p.m. and a journalist in Champaign is ending the night like she always does, with a cup of peppermint tea and news from the BBC World Service on AM 580. Despite the generally unhappy nature of global news, hearing it helps her to feel human, to feel empathy for other people she’ll never meet, whose situations are so different from her own, and she feels grateful that she’s able to listen.

The journalist has been ending the night exactly like this for much of the past 30 years. When her children were young, she and her husband would put them to bed and come downstairs, glassy-eyed and ready to drop. Her husband would fill the kettle, she’d turn on the radio and they’d settle in. Today, their kids are grown, but otherwise their routine is the same.

When the journalist wakes up tomorrow at her usual time, 4 a.m., her husband still asleep, she’ll go to the kitchen, get the coffee brewing, and start the day the way she ended it: with the radio on—the BBC still “reporting from London,” fighting the good fight in the overnight hours, as people around the world listen and reflect or sleep and dream.

Thus ends a day in the life of WILL, the station that once called itself “The University of the Air.” But as its audience can attest, what WILL really is—what it always has been—is a community center of the air. It’s a place where listeners and viewers from the cities and towns and lonely country roads of Illinois come together to learn and grow, to bear witness to the joys and struggles of others, and to search for the truth and beauty that illuminate our world; and in that search, they become the wisest, most open-minded and most empathetic versions of themselves.

Congratulations to WILL on a century of public broadcasting for the public good, from the millions of people whose lives it’s made richer over the past 100 years.